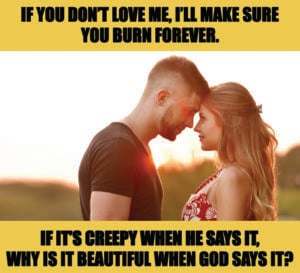

Obviously, the meme above is meant to express the alleged incompatibility between the Christian doctrine of hell and its belief that God is all good. How can God be all good and all loving, so the argument goes, and at the same time will that someone experience eternal torment?

There are two possible reasons why someone might think that God and hell are incompatible. One is that punishment itself is a bad thing. If that were the case, then surely an all-good God wouldn’t punish someone.

The other possible hangup is the eternal nature of hell. One may say, “Okay, I can accept punishment as consistent with God’s goodness, but I can’t accept eternal punishment. That seems unjust and therefore contrary to God’s goodness.”

There are two objections here, so let’s deal with each in turn. Let’s take the first objection from punishment.

Privation as natural punishment

Our first line of response is that the punishment of hell is primarily the privation of the ultimate joy that every human being longs for, which is a natural consequence that flows from a person’s rejection of God as their ultimate end, the source of all joy (see Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1057). As St. Augustine taught, our hearts are made for God and they are restless until they rest in him (The Confessions, book 1).

If a person chooses to separate himself from God for eternity, the state of restlessness or misery is simply a natural consequence. The torment follows from the way God has designed human nature.

Consider these two scenarios. Suppose a father tells his son, “If you want to go to the movies, then you have to clean your room,” and the son chooses not to clean his room. The result of his choice is that he doesn’t get to go to the movies. He throws a fit. His “pain,” the deprivation of not seeing a movie, is a consequence of his choice. But notice that the connection between the consequence and the choice is not natural. The father imposes it.

Contrast this with the scenario of an individual who intentionally puts a plastic bag over his head and asphyxiates. The painful effect of death is a natural consequence of stopping his supply of oxygen. It belongs to his nature that he needs oxygen to live. If he doesn’t have oxygen, then he doesn’t have life.

Similarly, it belongs to human nature for a person to be united to God in order to have complete and perfect happiness. If he’s not united to God, then he has no happiness and only misery.

Why would it be contrary to God’s goodness to allow human nature to function according to the design he created? If God decides to create something with a particular nature, then it belongs to his goodness to treat that thing according to its nature.

God made humans to be in union with him for an eternity. Therefore, if anyone chooses to reject such union and end up separated from God for an eternity, which is the essence of hell (CCC 1033), his misery would be the natural result given his nature. And there is nothing contrary to God’s goodness to allow nature to take its course—whether it takes it in beatitude with God in heaven or in misery without him in hell.

Respecting our choice

Now, God also created us with the capacity to choose or reject him. Therefore, if a person rejects God and doesn’t wish to be with him, then it would belong to God’s goodness to respect that free choice and not coerce the person into choosing him; otherwise, God would be violating the nature with which he created him.

Moreover, for God to coerce a person into choosing him would undermine the loving relationship he wills to have with that person in the first place. Imagine a man makes a romantic advance to a woman, and she rejects him. But then he grabs her and tries to kiss her anyway. Would that be an expression of love? Of course not!

The same principle applies to God and those who reject him. Given that God wills to have a loving relationship with humans (and the angels), he doesn’t coerce them into choosing him. Of course, this leaves room for the possibility for a rational creature to choose to be definitively separated from God. But for those who end up definitively separated, it’s due to their free choice.

As C.S. Lewis writes in The Great Divorce, “There are only two kinds of people in the end: those who say to God, ‘Thy will be done,’ and those to whom God says, ‘Thy will be done.’” Hell is for the latter. All those who end up there choose it.

Secondary punishment from God

Now, someone might object, “Wait. You said that the punishment of hell is primarily the deprivation of seeing God. That implies a secondary form of punishment, does it not? And doesn’t St. Thomas Aquinas teach in chapter 140 of book 3 in his Summa Contra Gentiles that this secondary form of punishment is of divine origin?”

Yes, it does imply a secondary form of punishment, though the nature of that punishment (whether it’s real material fire or not) is uncertain. And, yes, Aquinas did teach that God inflicts this punishment. But this doesn’t contradict God’s goodness. Punishment, when considered in and of itself, is a good.

Following the lead of philosopher Edward Feser in his online article “Does God Damn You?”, we can start by articulating the natural relationship between pain and pleasure on the one hand and good and bad behavior.

Nature ordains that we have feelings of delight or well-being when we have good behavior, which is behavior that is consistent with the ends that nature directs us to as human beings (self-preservation, sexual reproduction, knowledge of the truth, experience of loving relationships, etc.). Because of this, pleasure is what some philosophers call a “proper accident” of good behavior. And since good behavior is what constitutes true human happiness, pleasure is a “proper accident” for happiness.

But, as with other proper accidents, like the four legs of a dog, this feeling of delight that naturally arises from good behavior can be blocked. A dog is supposed to have four legs, but it may end up having only three legs due either to the leg being removed or to genetic defect.

Similarly, as Feser points out, it’s possible that “circumstances or psychological harm can prevent someone from taking pleasure in the realization of the ends toward which he is naturally directed.” The pleasure that is meant to be experienced from good behavior can be blocked. And in many cases, unpleasantness is the actual result of the good behavior.

The same line of reasoning applies to pain. Like pleasure, pain is a “proper accident.” But, unlike pleasure, pain is a “proper accident” of bad behavior, which is behavior that is not consistent with the ends to which nature directs us.

Whenever we behave in a way that is inconsistent with what our nature dictates, painful or unpleasant consequences naturally ensue. For example, we may have a guilty conscience, or we may feel dissatisfied. We may feel frustration, anxiety, humiliation, shame, or even self-hatred. In some cases, there is even physical illness, as in the case when we eat or drink too much or eat or drink bad things.

Now, even though nature ordains unpleasant experiences to follow bad behavior, this natural flow can be blocked, as in the case of pleasure. There are many ways in which we can do this.

For example, we’re all familiar with hiding our bad behavior in order to avoid punishments and criticism. We’re also all too familiar with trying to rationalize our behavior in order to explain away shame and guilt. We might say that those who criticize us don’t know any better and are just ignorant.

Perhaps we might rationalize our behavior by looking to others who engage in it, and saying, “See, they do it, so it can’t be that bad.” Some even lock arms with those who engage in the same bad behavior and trick themselves into thinking that it’s actually good, and anyone who opposes it is evil or mean-spirited.

The bottom line is that the unpleasant feelings that we’re meant to experience with bad behavior can be blocked, and in some circumstances we rationalize our behavior so much that pleasant feelings follow.

It’s this natural order that exists between pleasure and pain and good and bad behavior that grounds the good of punishment when considered in and of itself.

Consider that when there is no delight experienced with good behavior, there is a real defect or dysfunction in nature. Things are not functioning the way they should. The same is true for bad behavior. When a person doesn’t experience unpleasant feelings, or even experiences pleasant feelings, when he acts in a way that is inconsistent with the ends to which nature directs him, something is awry. Things aren’t functioning as they ought to function.

So, in both cases things need to be made right and restored back to order. The disorder present when there is no pleasure or even unpleasant feelings associated with good behavior needs to be brought to order by seeing to it that the good behavior is rewarded with pleasure.

And the disorder present when there is pleasure associated with bad behavior needs to be brought to order by seeing to it that the bad behavior is punished with pain. And this is the essence of punishment.

Based on this understanding of the goodness of punishment, we can say that the belief of a secondary punishment in hell whereby God positively inflicts harm on the damned doesn’t conflict with his goodness.

The eternity of hell

Okay, someone may concede that punishment in general is not inconsistent with God’s goodness. “But,” they’ll say, “eternal punishment? Doesn’t that seem unjust, since eternal punishment would be disproportionate to the sin that’s committed only in a small moment of time?”

Here are a few ways we can respond.

First, the objection assumes that a punishment has to be equal or proportionate to a fault as to the amount of duration. But this is false. If the duration of punishment had to correspond to the duration of an offense, then it would be unjust to give a murderer a prison sentence any longer than the time it took for the murderer to kill his victim.

But that’s absurd. As the Jesuit philosopher Bernard Boedder writes, “[T]ime cannot be the standard by which punishment is to be determined” (Natural Theology, 340).

The measure of the punishment due for sin is the gravity of the fault. Aquinas explains, “The measure of punishment corresponds to the measure of fault, as regards the degree of severity, so that the more grievously a person sins the more grievously is he punished” (Summa Theologiae, suppl. III:99:1). In other words, it is the internal wickedness of an offense that is the measure of expiation for it.

Now, as Aquinas points out in several places within his writings, the gravity of an offense is determined by the dignity of the person sinned against. For example, punishment for striking the president of the United States is going to be greater than punishment for striking Joe Blow in a bar brawl.

Since God is ipsum esse subsistens (“subsistent being itself” ), he is infinite in dignity and majesty. Therefore, his right to obedience from his reasonable creatures is absolute and infinite. There is no right that can be stricter, and every other right is based on it.

A willful violation of this right, which is what a mortal sin is, is the most severe offense a human being can commit. Boedder explains it this way: “A willful violation . . . of this right implies a malice which opposes itself to the foundation of all orders” (Natural Theology, 340).

For Aquinas, it is an offense that is “in a certain respect infinite” (Compendium Theologiae, 183). And because it is infinite in a certain respect, Aquinas concludes, “a punishment that is in a certain respect infinite is duly attached to it.”

But, as Aquinas points out, such a punishment can’t be infinite in intensity, because no creature can be infinite in this way. Therefore, Aquinas concludes, “[A] punishment that is infinite in duration is rightly inflicted for mortal sin.”

It’s important to note that, for Aquinas, an infinite duration of punishment can be just only if the sinner no longer has the ability to repent and will the good. Well, the sinner after death no longer has the ability to repent, since after death the soul can no longer change what it has chosen as its ultimate end. Therefore, we can conclude with Aquinas that the infinite duration of punishment in hell is just.

The alternatives don’t work

Another way that we can respond to the “Eternal punishment is unjust” objection is to see that the alternatives to eternal punishment—temporary punishment or annihilation—don’t stand up to the scrutiny of reason.

Consider temporary punishment. Perhaps the soul receives an intense dose of punishment and then enters heaven upon being relieved of it. This would be an injustice. For example, let’s say I find out that my fourteen-year-old son ditched school and went to a party with his older teen friends and got drunk and smoked a joint (this is merely hypothetical, mind you).

Suppose further that I punish him by saying, “Son, you’ve been a bad boy, and as a result you’re going to stay in your room for ten minutes. But when that time is up, pack your bags because we’ve got tickets to spend the weekend at Disneyland.”

How does this register on your justice monitor? My guess is that it doesn’t rate very high—especially if my son refuses to apologize for his misconduct. The duration of the punishment is much too small relative to the reward he is given.

Similarly, a temporary stint in hell—no matter how long the term—is much too small of a punishment relative to the everlasting happiness of heaven. It would be unjust for God to give heaven as a reward to a person that committed the most grievous offense of all, the permanent rejection of God’s absolute right to obedience, worship, and love.

Annihilation is also an unreasonable alternative. How could a person experience the punishment justice demands for permanently rejecting God if he were annihilated? The gravity of violating God’s absolute right would be reduced to nothingness if there were no punishment for it. Justice would not be served.

Furthermore, it would violate God’s wisdom to annihilate the human soul. Why would he create a human soul with an immortal nature only to thwart it?

Circling back to the meme

With all that said, let’s come back to our meme. It’s true that it would be unloving for the young man to ensure that his girlfriend burn (or be punished) for rejecting him. But the same can’t be said when it comes to God.

The young man is not the infinite God with infinite dignity to whom the young girl is directed as her ultimate end and to whom she must give absolute obedience. God and the young man are on two totally different metaphysical playing fields.

Moreover, because the young girl is not directed to the young man as her ultimate end, her choice to not direct her life to him doesn’t entail a disorder. As such, her rejection of the young man isn’t deserving of punishment, much less eternal punishment, since there is no disorder to order.

The meme, therefore, fails to convey its intended message: that the doctrine of hell and belief in an all-good God are incompatible. In fact, the opposite is true. The doctrine of hell manifests God’s goodness. Hell is a reality only because God wills that we have the dignity to determine whether we want to enter into an everlasting loving relationship with him or not. There’s nothing unloving about that! When you think about it, it’s quite beautiful.

Sidebar

Won’t the Blessed Feel Sorry for the Damned?

The Catechism of the Catholic Church teaches that at the Last Judgment “the truth of each man’s relationship with God will be laid bare” (CCC 1039). This means the blessed in heaven will know which of their loved ones are in hell. But how could that be if heaven is a “state of supreme, definitive happiness” (CCC 1024)? Wouldn’t the blessed pity the damned, knowing the sufferings they undergo?

Notice the question assumes that the blessed pity the damned, which of course would create sorrow and undermine happiness. But we have good reason to think the blessed don’t pity the damned.

Pity comes only when a person wishes another’s evil would cease. So, if it were the case that one didn’t wish for another’s evil to cease, then there would be no pity.

When applied to the blessed in heaven and their relation to the damned, we can affirm the antecedent: the blessed in heaven don’t wish for the suffering of the damned to cease.

One reason is that they will the order of divine justice that is annexed to the suffering of the damned (see ST suppl. III:94:2). For the blessed to will that the suffering of the damned might cease would be to will something contrary to God’s justice, which the blessed can’t do.

Another reason is that they can’t wish for that which is metaphysically impossible. Given the irrevocability of choice after death, the damned are incapable of changing the direction of their will. Their wills are fixed on evil, leaving nothing good within them.

This leads to another reason: the blessed no longer see the damned as their “loved” ones. Given that the damned are fixed on evil, and there is no good left within them except for their existence, there is nothing there to ground a loving relationship. The loving relationship that would have been a motivation for pity in this life is gone.

Since the blessed don’t pity the damned, it follows that they don’t share in their unhappiness. And if that’s the case, then no problem exists in the assertion that the blessed in heaven are definitively happy and at the same time know the hellish sufferings of those whom they loved while here on Earth.