What Are the Seven Gifts of the Holy Spirit?

The seven gifts of the Holy Spirit are, according to Catholic Tradition, wisdom, understanding, counsel, fortitude, knowledge, piety, and fear of God. The standard interpretation has been the one that St. Thomas Aquinas worked out in the thirteenth century in his Summa Theologiae:

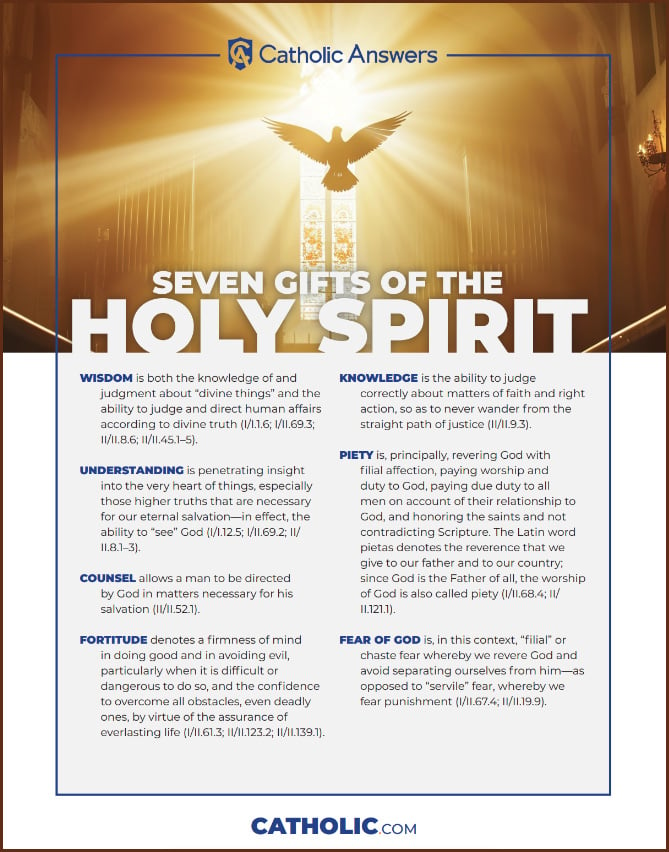

- Wisdom is both the knowledge of and judgment about “divine things” and the ability to judge and direct human affairs according to divine truth (I/I.1.6; I/II.69.3; II/II.8.6; II/II.45.1–5).

- Understanding is penetrating insight into the very heart of things, especially those higher truths that are necessary for our eternal salvation—in effect, the ability to “see” God (I/I.12.5; I/II.69.2; II/II.8.1–3).

- Counsel allows a man to be directed by God in matters necessary for his salvation (II/II.52.1).

- Fortitude denotes a firmness of mind in doing good and in avoiding evil, particularly when it is difficult or dangerous to do so, and the confidence to overcome all obstacles, even deadly ones, by virtue of the assurance of everlasting life (I/II.61.3; II/II.123.2; II/II.139.1).

- Knowledge is the ability to judge correctly about matters of faith and right action, so as to never wander from the straight path of justice (II/II.9.3).

- Piety is, principally, revering God with filial affection, paying worship and duty to God, paying due duty to all men on account of their relationship to God, and honoring the saints and not contradicting Scripture. The Latin word pietas denotes the reverence that we give to our father and to our country; since God is the Father of all, the worship of God is also called piety (I/II.68.4; II/II.121.1).

- Fear of God is, in this context, “filial” or chaste fear whereby we revere God and avoid separating ourselves from him—as opposed to “servile” fear, whereby we fear punishment (I/II.67.4; II/II.19.9).

These are heroic character traits that Jesus Christ alone possesses in their plenitude but that he freely shares with the members of his mystical body (i.e., his Church). These traits are infused into every Christian as a permanent endowment at his baptism, nurtured by the practice of the seven virtues, and sealed in the sacrament of confirmation. They are also known as the sanctifying gifts of the Spirit, because they serve the purpose of rendering their recipients docile to the promptings of the Holy Spirit in their lives, helping them to grow in holiness and making them fit for heaven.

These gifts, according to Aquinas, are “habits,” “instincts,” or “dispositions” provided by God as supernatural helps to man in the process of his “perfection.” They enable man to transcend the limitations of human reason and human nature and participate in the very life of God, as Christ promised (John 14:23). Aquinas insisted that they are necessary for man’s salvation, which he cannot achieve on his own. They serve to “perfect” the four cardinal or moral virtues (prudence, justice, fortitude, and temperance) and the three theological virtues (faith, hope, and charity). The virtue of charity is the key that unlocks the potential power of the seven gifts, which can (and will) lie dormant in the soul after baptism unless so acted upon.

Because “grace builds upon nature” (ST I/I.2.3), the seven gifts work synergistically with the seven virtues and also with the twelve fruits of the Spirit and the eight beatitudes. The emergence of the gifts is fostered by the practice of the virtues, which in turn are perfected by the exercise of the gifts. The proper exercise of the gifts, in turn, produces the fruits of the Spirit in the life of the Christian: love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, generosity, faithfulness, gentleness, modesty, self-control, and chastity (Gal. 5:22–23). The goal of this cooperation among virtues, gifts, and fruits is the attainment of the eight-fold state of beatitude described by Christ in the Sermon on the Mount (Matt. 5:3–10).

Unfortunately, it is difficult to name another Catholic doctrine of as hallowed antiquity as the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit that is subject to as much benign neglect. Like most Catholics born around 1950, I learned their names by rote: “wis-dom, un-derstanding, coun-sel, fort-itude, know-ledge, pie-ety, and fear of the Lord!” Sadly, though, it was all my classmates and I ever learned, at least formally, about these mysterious powers that were to descend upon us at our confirmation. Once Confirmation Day had come and gone, we were chagrined to find that we had not become the all-wise, all-knowing, unconquerable milites Christi (soldiers of Christ) that our pre-Vatican II catechesis had promised.

The Problem

Ironically, post-Vatican II catechesis has proven even less capable of instilling in young Catholics a lively sense of what the seven gifts are all about. At least the previous approach had the advantage of conjuring up the lurid prospect of a martyr’s bloody death at the hands of godless atheists. But, alas, such militant pedagogy went out the window in the aftermath of the Council. But a stream of reports in recent decades on declining interest in the faith among new confirmandi suggests that the changes are not having their desired effect. Not that there were no bugs in the pre-Vatican II catechetical machine—there were plenty—but such superficial tinkering did not even begin to address them.

A recent article in Theological Studies by Rev. Charles E. Bouchard, O.P., president of the Aquinas Institute of Theology in St. Louis, Missouri (“Recovering the Gifts of the Holy Spirit in Moral Theology,” Sept. 2002), identifies some specific weaknesses in traditional Catholic catechesis on the seven gifts:

- Neglect of the close connection between the seven gifts and the cardinal and theological virtues (faith, hope, charity/love, prudence, justice, fortitude/courage, and temperance), which St. Thomas Aquinas himself had emphasized in his treatment of the subject

- A tendency to relegate the seven gifts to the esoteric realm of ascetical/mystical spirituality rather than the practical, down-to-earth realm of moral theology, which Aquinas had indicated was their proper sphere

- A form of spiritual elitism whereby the fuller study of the theology of the gifts was reserved to priests and religious, who alone, it was presumed—unlike the unlettered masses—had the requisite learning and spirituality to appreciate and assimilate it

- Neglect of the scriptural basis of the theology of the gifts, particularly Isaiah 11, where the gifts were originally identified and applied prophetically to Christ

The 1992 Catechism of the Catholic Church had already addressed some of these issues (such as the importance of the virtues and the relationship between the gifts and “the moral life”) but avoided defining the individual gifts or even treating them in any detail—a mere six paragraphs (1285–1287, 1830–1831, and 1845), as compared with forty on the virtues (1803–1829, 1832–1844). Perhaps that is why the catechetical textbooks that have appeared in the wake of the new Catechism present such a confusing array of definitions of the gifts. These definitions tend to be imprecise re-hashings of the traditional Thomistic definitions or totally ad hoc definitions drawn from the author’s personal experience or imagination.

The Seven Gifts of the Holy Spirit and the Spiritual Arsenal

Rather than perpetuating either a strictly Thomistic approach or an approach based on contemporary, culturally conditioned definitions, I propose a third way of understanding the seven gifts, one that goes back the biblical source material.

The first—and only—place in the entire Bible where these seven special qualities are listed together is Isaiah 11:1–3, in a famous Messianic prophecy:

There shall come forth a shoot from the stump of Jesse, and a branch shall grow out of his roots. And the Spirit of the Lord shall rest upon him, the spirit of wisdom and understanding, the spirit of counsel and might, the spirit of knowledge and the fear of the Lord. And his delight shall be in the fear of the Lord.

Virtually every commentator on the seven gifts for the past two millennia has identified this passage as the source of the teaching, yet none have noted how integral these seven concepts were to the ancient Israelite “Wisdom” tradition, which is reflected in such Old Testament books as Job, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs, Psalms, Ecclesiasticus, and the Wisdom of Solomon, as well as certain strands of the prophetic books, including Isaiah. This material focuses on how to navigate the ethical demands of daily life (economics, love and marriage, rearing children, interpersonal relationships, the use and abuse of power) rather than the historical, prophetic, or mythical/metaphysical themes usually associated with the Old Testament. It does not contradict these other aspects of revelation but complements them by providing a glimpse into how Israel’s covenant with Yahweh is lived out in all its nitty-gritty detail.

It is from this world of practical, down-to-earth, everyday concerns rather than the realm of ascetical or mystical experience that the seven gifts emerged, and the context of Isaiah 11 reinforces this frame of reference. The balance of Isaiah describes in loving detail the aggressiveness with which the “shoot of Jesse” will establish his “peaceable kingdom” upon the earth:

He shall not judge by what his eyes see, or decide by what his ears hear; but with righteousness he shall judge the poor, and decide with equity for the meek of the earth; and he shall smite the earth with the rod of his mouth, and with the breath of his lips he shall slay the wicked. . . . They shall not hurt or destroy in all my holy mountain; for the earth shall be full of the knowledge of the Lord as the waters cover the sea. (Is. 11:3–4, 9)

Establishing this kingdom entails thought, planning, work, struggle, courage, endurance, perseverance, humility—that is, getting one’s hands dirty. This earthbound perspective is a profitable one from which to view the role the seven gifts play in the life of mature (or maturing) Christians.

There is a strain within Catholicism, as within Christianity in general, that focuses on the afterlife to the exclusion—and detriment—of this world, as if detachment from temporal things were alone a guarantee of eternal life. One of the correctives to this kind of thinking issued by Vatican II was the recovery of the biblical emphasis on the kingdom of God as a concrete reality that not only transcends the created order but also transforms it (Dei Verbum 17; Lumen Gentium 5; Gaudium et Spes 39).

The seven gifts are indispensable resources in the struggle to establish the kingdom and are, in a sense, a byproduct of actively engaging in spiritual warfare. If a person does not bother to equip himself properly for battle, he should not be surprised to find himself defenseless when the battle is brought to his doorstep. If my classmates and I never “acquired” the “mysterious powers” we anticipated, perhaps it is because we never took up arms in the struggle to advance the kingdom of God!

The seven gifts are an endowment to which every baptized Christian can lay claim from his earliest childhood. They are our patrimony. These gifts, given in the sacraments for us to develop through experience, are indispensable to the successful conduct of the Christian way of life. They do not appear spontaneously and out of nowhere but emerge gradually as the fruit of virtuous living. Nor are they withdrawn by the Spirit once they are no longer needed, for they are perpetually needed as long as we are fighting the good fight.

The seven gifts are designed to be used in the world for the purpose of transforming that world for Christ. Isaiah 11 vividly portrays what these gifts are to be used for: to do what one is called to do in one’s own time and place to advance the kingdom of God. The specific, personal details of that call do not come into focus until one has realized his very limited, ungodlike place in the scheme of things (fear of the Lord), accepted one’s role as a member of God’s family (piety), and acquired the habit of following the Father’s specific directions for living a godly life (knowledge). This familiarity with God breeds the strength and courage needed to confront the evil that one inevitably encounters in one’s life (fortitude) and the cunning to nimbly shift one’s strategies to match—even anticipate—the many machinations of the Enemy (counsel). The more one engages in such “spiritual warfare,” the more one perceives how such skirmishes fit into the big picture that is God’s master plan for establishing his reign in this fallen world (understanding) and the more confident, skillful, and successful one becomes in the conduct of his particular vocation (wisdom).

Soldiers of Christ

These remarks are aimed primarily at adult cradle Catholics who, like me, were inadequately catechized (at least with respect to the seven gifts). Because of the ongoing controversy in the Church at large over the proper age for reception of the sacrament of confirmation, the malaise of inadequate catechesis is likely to continue afflicting the faithful. The lack of attention to the synergistic relationship between the virtues and the gifts of the Holy Spirit seems to be the main culprit in the failure to develop the gifts among the confirmandi. Catechesis that is aimed only at the acquisition of knowledge or merely at promoting “random acts of kindness” without a solidly evangelical organizing principle simply will not cut it with this (or any other) generation of young people. Centering prayer, journaling, guided meditation, or any of the host of other pseudo-pedagogical tricks popular in many current catechetical programs cannot compete with the seductions of the culture of death.

The path to a mature appropriation of the spiritual arsenal represented by the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit needs to be trod as early as possible, and the seven virtues can serve today, as they have for most of the Church’s history, as excellent guides along that path. Perhaps it is time to resurrect the traditional image of the baptized as “soldiers of Christ,” a phrase that has been anathema for Catholic catechetical materials for decades. Despite the fact that the post-Vatican II zeitgeist has militated against the notion of “militancy” in all things religious, this stance has been shown to be misguided—by an honest assessment of what Sacred Scripture has to say about it and by world events in our own lifetime. The toppling of the Soviet Union, for example, would not have happened without the nonviolent militancy of John Paul II in the pursuit of a legitimate goal. The seven gifts of the Holy Spirit are our spiritual weaponry for the spiritual warfare of everyday life.