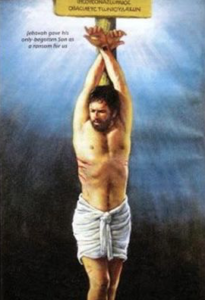

Jehovah’s Witnesses believe that the Greek word translated as “cross” in the New Testament, stauros, actually means “upright stake” or, in their words, “torture stake.” They claim that Jesus was nailed through both wrists on a large vertical stake without a crossbeam (pictured below). They even go so far as to claim, “True Christians do not use the cross in worship.”[0]

Oddly enough, this belief was not present in the earliest doctrines of the Jehovah’s Witnesses. Their second president, Joseph Rutherford, taught, “The cross of Christ is the greatest pivotal truth of the divine arrangement, from which radiate the hopes of men.”[1] It was not until the late 1930s that Rutherford changed the Witnesses’ position on this issue.

Now, when it comes to disagreements Catholics have with the Witnesses, this is a minor one. But it is still important to address the Witnesses’ arguments related to this issue. If they are able to convince people to abandon the cross, it becomes easier to convince them to abandon the Christian faith that embraces the cross.

Evidence for a Stake?

In the article cited above, the Witnesses make the claim that stauros means only a stake and never means two pieces of timber joined into a cross. They also say that in other passages (e.g., Acts 5:30, Galatians 3:13, 1 Peter 2:24) the Greek word xulon that is used means simply “timber.” Finally, the Witnesses point out that in Galatians 3:13 Paul quotes Deuteronomy 21:22-23 (“Cursed be every one who hangs on a tree”) in reference to Christ’s death. They say this shows Jesus wasn’t hung on a cross, because the passage in Deuteronomy refers to hanging from trees, not crosses.

But these arguments fail to prove their conclusion.

First, stauros can mean upright stake, but that is not the word’s only meaning. Kittel’s Theological Dictionary says of a stauros:

In shape we find three basic forms. The cross was a vertical, pointed stake (skolops, 409, 4 ff.), or it consisted of an upright with a cross-beam above it (T, crux commissa), or it consisted of two intersecting beams of equal length (†, crux immissa).[2]

The first-century Roman philosopher Seneca the Younger described crucifixions in a variety of ways. He writes:

I see before me crosses not all alike, but differently made by different peoples: some hang a man head downwards, some force a stick upwards through his groin, some stretch out his arms on a forked gibbet (emphasis added).[3]

In regards to xulon, according to Strong’s Concordance (3586), a xulon can refer to anything made from wood, be it a stake, a tree, or a cross. So its use in Paul’s citation of Deuteronomy 21:22-23 does not rule out Jesus being executed on a cross. Paul is simply using this verse to foreshadow Christ’s death, not to explicitly describe it.

In fact, the Witnesses’ argument disproves their own view that a wooden stake was used, because Deuteronomy 21:22-23 more naturally refers to hanging someone from a literal tree (or in Hebrew an ‘ets), not a stake.[4] If the Witnesses can say Paul was using the tree language as a foreshadowing of a stake, then Christians can use the same argument for a foreshadowing of the cross upon which Jesus really died. A tree actually has more in common with a cross than a stake, because most trees have branches.

Finally, just because something is described as a stake or a pole does not mean it is a single, vertical shaft. For example, we refer to the thing that holds up power lines as a utility pole, even though it is usually fashioned in the shape of a cross.

Evidence for the Cross

So why think Jesus was crucified on a cross and not a stake?

First, if a stake were used instead of a cross, then only one nail would have been driven through Jesus’ overlapping wrists (once again, see the above picture). But this doesn’t explain why John 20:25 refers to the nails that were used to affix Jesus to the cross. This means that Jesus’ arms were stretched out on a cross and one nail was driven through each arm, not one nail through both arms on a stake.

In addition, Matthew 27:37 says, “[O]ver his head they put the charge against him, which read, ‘This is Jesus the King of the Jews.’” But if Jesus were crucified on a stake, then the sign would be placed directly above his hands, not his head.

We also have evidence that the early Christians believed Jesus was crucified on a cross, not a stake. In the year A.D. 100, the epistle of Barnabas described how Jesus’ outstretched arms on the cross were similar to Moses’ outstretched arms in a battle with the Amalekites.[5]

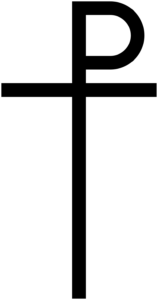

The second-century apologist Justin Martyr eloquently described the crossbeams used to crucify Jesus.[6] In the third century, Tertullian said that Christians used the Greek letter tau, or “T,” as a sign of the cross.[7] Biblical scholar Larry Hurtado has even shown how Christian writers in the second century combined the Greek letters for T and R in order to create a symbol that represented the crucifixion called a staurogram.[8] In the image below you can see how the letters model a figure with his arms outstretched on a cross.

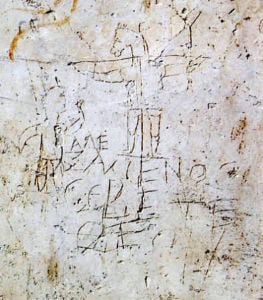

Additionally, an ancient drawing called the Alexamanos graffito shows a Roman soldier worshipping a man with a donkey head being crucified.

It has been dated to the early third century and was probably intended to mock Christians who worshipped a victim of crucifixion. The caption reads, “Alexamanos worships [his] God.” Tertullian references such parodies in his own writings.[9]

To summarize, the Jehovah’s Witnesses have no evidence that the passages in Scripture concerning the cross must refer to a stake. They also cannot account for the abundant evidence among the early Christians who believed that Jesus was executed on a cross and not a stake.

[0] http://www.jw.org/en/publications/books/bible-teach/why-true-christians-do-not-use-the-cross-in-worship/

[1] Joseph Rutherford. The Harp of God (Brooklyn, NY: Watchtower Bible and Tract Society, 1921) 141.

[2] Gerhard Kittel, Theological Dictionary of the New Testament: Volume 7 (1971) 572.

[3] Seneca the Younger, “To Marcia on Consolation”, in Moral Essays, 6.20

[4] However, the word can refer to a gallows, or a platform used to hang someone (see Esther 2:23).

[5] Barnabas 12:2

[6] Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho, 40.

[7] Tertullian, Ad nationes, 1.11

[8] Larry Hurtado, The Earliest Christian Artifacts: Manuscripts and Christian Origins (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2006), 135-54.

[9] Walter Drum, “The Incarnation.” The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 7. (New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910). http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/07706b.htm Tertullian writes, “some among you have dreamed that our god is an ass’s head—an absurdity which Cornelius Tacitus first suggested.” Ad nationes, 1.11