Many atheists think that faith and reason mix as well as oil and water; some actually cite early Christian writings in order to make their case. One writer they like to quote is Tertullian, who allegedly said he believed in the gospel because it’s absurd.

Tertullian lived in North Africa in the third century and is often considered the father of Latin or Western Christianity. Even though he became a heretic at the end of his life and died out of communion with the Church (which is why even though he’s considered a Church Father he’s not a saint), his earlier, orthodox writings are an important witness to the antiquity of the Faith. People who say Tertullian is also an ancient witness to the unreasonableness of Christianity usually cite two of his writings.

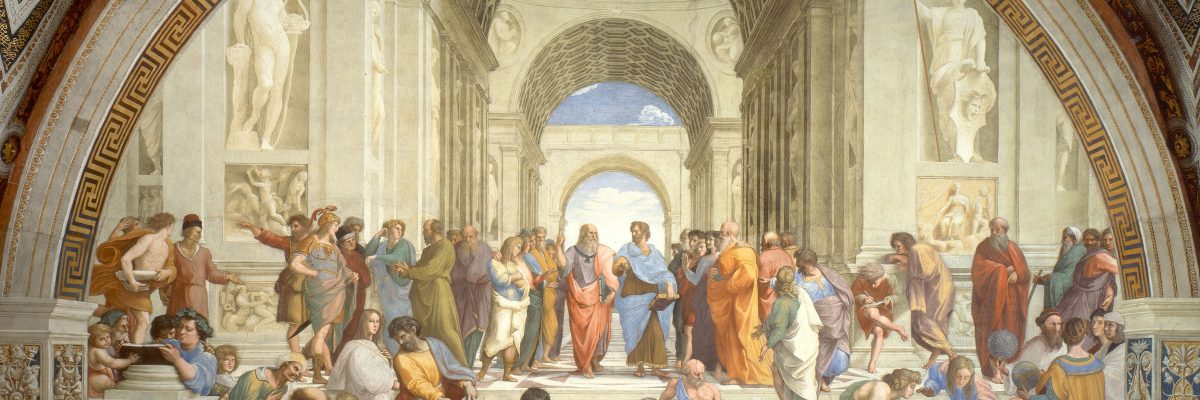

Faith vs. philosophy?

The first is Tertullian’s question, “What has Athens to do with Jerusalem?” from his Prescription Against Heretics. Critics say that what Tertullian means is that faith (Jerusalem) and reason (Athens) should have nothing to do with each other. But Tertullian was speaking in the context of St. Paul’s warning to not be captivated by “philosophy and empty deceit” (Col. 2:8), typified, he said, by philosophers at Athens who pretended to know the truth but actually corrupted it. He was not condemning all philosophy or reasoning in general.

Modern scholarship has come to recognize this. According to the Cambridge History of Literary Criticism, “The older view, that Tertullian was a spokesman for complete separation of Christianity and Classical culture, has in recent years given way to increased recognition in his writings of a synthesis of Christian doctrine with philosophical traditions” (337).

Believe because it is absurd?

In his book A Devil’s Chaplain, atheist Richard Dawkins likens faith to a malevolent virus that is difficult to cure because its victims ignore its alleged absurdities. When a victim is confronted with parts of his faith that are difficult to understand, he simply calls them “mysteries” and fails to give them any more attention. Dawkins writes, “An extreme symptom of ‘mystery is a virtue’ infection is Tertullian’s ‘Certum est quia impossibile est’ (It is certain because it is impossible) [and], ‘it is by all means to be believed because it is absurd.’”

Dawkins is referring to a passage from Tertullian’s De Carne Christi (On the Flesh of Christ), which was a response to the heresy of Docetism. The Docetists believed that the incarnate Son, Jesus Christ, did not possess a real human body. Instead, he possessed what appeared to be a human body but was actually an illusory or angelic form. Tertullian criticized the Docetists because if Christ did not have a truly human and truly physical body, then he could not have died on the cross and atoned for humanity’s sins. The Cambridge History of Literary Criticism notes:

Tertullian’s writings do not include the words “I believe because it is absurd,” and the origin is unknown. The closest to the sentiment in his works is the statement: “The Son of God was crucified: there is no shame, because it is shameful. And the Son of God died: it is believable because it is foolish. And buried, he rose again; it is certain because it is impossible” (De carne Christi 5.4). This is as good a short example as could be found of Tertullian’s pointed style (337).

So Tertullian never says, “I believe because it is absurd” (Latin: credo quia absurdum). This appears to be a paraphrase of a line many translators render “it is by all means to be believed, because it is absurd” (original Latin: prorsus credibile est, quia ineptum est). Since the Latin word absurdum is not in this passage, a better translation of the second line would be, “It is credible, because it is foolish.” However, Tertullian is not arguing that foolish things, on their own, are credible or believable because they’re foolish.

Absurd not to believe

Rather, his claim is that the first Christians would not have believed God died on a cross and then rose from the dead unless that really happened. If Jesus was not who he claimed to be, then those first potential believers would have thought he was just another failed messiah and would have rejected the “absurd” tale that Jesus rose from the dead. The reason the first Christians did not do this, however, is because they experienced the impossible with their own eyes when Jesus appeared to them after his crucifixion. St. Luke makes a point of telling his readers that Jesus “presented himself alive after his passion by many proofs, appearing to [the apostles] during forty days, and speaking of the kingdom of God” (Acts 1:3).

Tertullian did not think God becoming man and dying for our sins was impossible because in this same work he wrote, “With God, however, nothing is impossible but what he does not will. Let us consider, then, whether he willed to be born (for if he had the will, he also had the power, and was born).” He just rightly recognizes how fantastic it is.

So, Tertullian’s statement, “It is by all means to be believed, because it is absurd” should therefore not be understood to mean that Christianity is irrational, but rather that the story of the life, death, and resurrection of the God-man is too ridiculous for someone to have made it up.