Do the damned suffer eternally in hell, or does God destroy them? In this episode, Trent sits down with Randal Rauser who defends “annihilationism,” the belief that God annihilates the damned and does not let them exist in hell for eternity.

Book Trent to speak at your parish or next event.

Want more from Trent Horn?

- Made This Way: How to Prepare Kids to Face Today’s Tough Moral Issues

- Why We’re Catholic: Our Reasons for Faith, Hope, And Love

- Persuasive Pro-Life: How to Talk About Our Culture’s Toughest Issue

- Answering Atheism: How to Make the Case for God with Logic and Charity

Welcome to the Counsel of Trent podcast, a production of Catholic Answers.

Trent Horn: Hello everyone and welcome to another episode of the Counsel of Trent. I am your host, Catholic Answers apologist and speaker, Trent Horn, and we’re continuing our tradition that we’ve started recently of having individuals come in to the podcast to dialogue with me about points where they disagree with the Catholic faith or we have other forms of disagreement. I’m very excited about that today. We’re going to introduce our guest in a moment, but I just want to remind you that your support of the podcast is what makes this possible. So without your support, we wouldn’t be able to fly in individuals like my guests I have had in today to have these important exchanges on these important matters. If you want to help to continue to support the podcast and make this kind of discussion possible, be sure to go and check it out at trenthornpodcast.com or if you are a premium subscriber, you get access to our catechism, our scripture study series, lots of other great bonus content. So do check that out at trenthornpodcast.com to make what we do here possible to reach many other people.

Trent Horn: Without further ado, I would like to introduce our guest today. He is Mr. Randal Rauser, evangelical theologian, who has been on the podcast before. We had a great conversation about arguments for and against atheism, so I’d thought it’d be fun to bring you back to talk about areas more where we might have disagreement and other important matters. Randal, why don’t you introduce yourself for our listeners who may not be as familiar with your work.

Randal Rauser: My name, as you said, is Randal. I’m a professor of historical theology at Taylor Seminary in Edmonton, Canada where I teach in theology, church history, and apologetics and world view is probably where my biggest interest lies. I’ve been teaching there for 16 years, written 10 or 11 books, including some co-authored books, and have a wife and one child and two dogs.

Trent Horn: Very good. You also have a blog called The Tentative Apologist, and I think that describes well your apologetic method and way you approach issues. Can you elaborate on that?

Randal Rauser: Yes. I have that and at my website, it’s my name RandalRauser.com, so I blog there. That conveys my commitment to recognizing while I can have these deep Christian convictions, I also hold them with a certain confidence that allows for questioning and doubt and clarification, and seeks to me the other people with a spirit of humility and hopefully invites them into a deeper conversation as we try to understand the truth together.

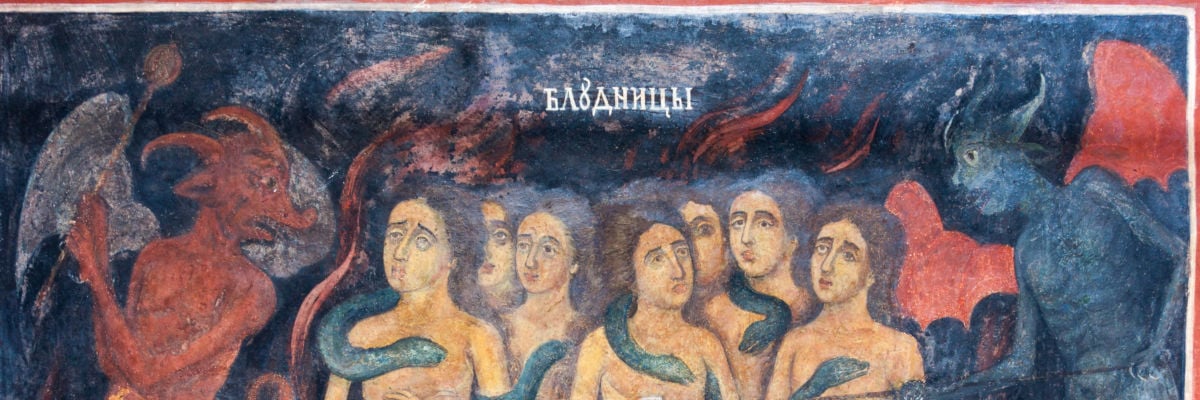

Trent Horn: Well I’d like to do that today, so we’re going to talk about, over a variety of episodes, a few different topics where we have disagreement. I always want to try to find guests that where I have disagreement with them on a wide variety of issues, including issues people haven’t heard about as much. So today, at least in this episode, what we’re going to talk about is the concept of annihilationism or conditional immortality. It’s a concept that’s gone by varying names, but the question we’re going to discuss that we have a disagreement on would be this: is hell forever? In what sense is it forever or eternal? Do those who are damned, those who permanently reject God and are consigned to hell, do they experience eternal conscious torment or not?

Trent Horn: You hold to a view, as I said, there’s different names that describe to it, that they do not, which would be contrary to kind of a longer Christian tradition that whatever hell is, it involves eternal conscious torment for the damned. When I was doing research for this discussion, I came across a movie, actually, a biopic if you will, and I saw that you had commented on it. The movie is called Hell and Mr. Fudge. At first I thought, this must be a prequel to Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, you would think. What else would lead them to the hellish images in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, but it’s a story of Edward Fudge. It kind of … He was one of the leading individuals to bring this concept back into discussion, especially among evangelicals. I don’t know if you want to speak to that.

Randal Rauser: Well yes. First of all, that is a pretty good movie worth watching and it does tell the story of Edward Fudge. I think back in the 1960s, he really began to wrestle with the concept of eternal conscious torment and under his own Biblical study, study of the scriptures, he came to the conclusion that in fact, hell involves a resurrection to destruction that results in the cessation of existence of the unregenerates or the damned. He eventually published that in a book called The Fire That Consumes. I believe it came out in 1982. So he’s continued to be a important, one of the important voices on this topic and in particular, representing this idea of annihilationism.

Trent Horn: Is that a label that you use, annihilationism or do you just prefer a different label to describe this belief?

Randal Rauser: Yes. So you’ll sometimes see the term conditional mortality. That term is a little bit more vague, I think, because conditional mortality could be just the view that you cease to exist when you die if you’re outside Christ or something. That’s not really the view. The more specific few if that there’s a general resurrection and that involves resurrection to judgment, which in the case of those outside Christ, as a result, in the cessation of their existence, so I would prefer the term annihilation, which more correctly conveys that idea.

Trent Horn: Another one I’ve seen, John Stackhouse Junior, I think, calls it terminal punishment, is one I’ve seen. Not as [inaudible 00:05:49], but I think annihilation or annihilationism is helpful for our discussion. I watched a few clips, actually, of Hell and Mr. Fudge, and I thought it was above average for Christian films.

Randal Rauser: Yeah, bar’s low.

Trent Horn: The bar can be a bit low there, though I did appreciate that Fudge’s dad was played by John Wesley Shipp, who was the original Flash in the 1990s Flash and currently is on the CW Flash as Jay Garrick from Earth-3 and Barry Allen from Earth-38. I have to let my comic book credentials come out a little when I saw that. I’m like, “John Wesley Shipp, love that guy.”

Trent Horn: Let’s go back to annihilationism.

Randal Rauser: I’m impressed by the way. That’s impressive.

Trent Horn: When it comes to annihilationism, Fudge is one of the big names in the 20th century to bring this out. I actually read a book. It was a Catholic reading guide to what they called conditionalism, especially annihilationism, and the preface of the book, the dedication I’d say, it was dedicated to those Protestant scholars that have returned this ancient thinking. I think there’s among certain annihilationists, there’s a thought that early on there was a belief in annihilationism, but throughout most of Christian history, that was kind of abandoned, and then it was brought back in the 20th century with people like Fudge. John Stott would probably be another famous figure behind that. Is that kind of your thought about what happened with this belief system?

Randal Rauser: Well yeah. I would like to say that there are in fact three broad views on the fate of the unregenerate in the Christian tradition. Those two that we’re primarily focusing on here, eternal conscious torment versus annhilation. And then there is a third view, universalism, which is not pluralism like there are many roads to the top of the mountain, but rather is the view that ultimately, there’s a hell after death, but it will result in the restoration, eventually, of all people to God and Christ.

Randal Rauser: I think all three of those views can be found throughout church history and it’s appropriate or one can say that annhilation and universalism are both what we would call minority reports in the history of the church. You can find representatives of them in the early church. With respect to annihilationism, someone like Irenaus seems to take an annihilationist position, Arnobius, so these are people in the second and third centuries.

Randal Rauser: Then, certainly after the time of Augustin, eternal conscious torment becomes more commonly held and sort of the majority view. With annihilationism, it becomes more significant in the 19th century, actually, within Anglicanism in particular, people like Charles Gore. Then into the 20th century, it continues to be very dominant or widespread in Anglicanism, so you mentioned Stott, Philip Hughes, Michael Green, another well known Anglican leader, and increasingly in the last 30 years, among evangelicals, it’s becoming a more widely held view.

Trent Horn: Yeah, because many of my Catholic listeners may not be as familiar with this, but I’ve seen, even evangelicals I know personally, you’re one among them, but even others have come to embrace this view and it’s a more common one, I’ve found, among the evangelical crowd. I think this is neat to introduce it, especially to my listeners who may not have heard of it as much. So Stott has a very famous quotation about his thoughts about his, Stott being as we referenced earlier, a very famous defender of annihilationism, his thoughts on hell. He puts it this way. They asked him do you believe in hell, at least eternal conscious torment? And he says, “Well, emotionally, I find the concept intolerable and do not understand how people can live with it without either cauterizing their feelings or cracking under the strain.”

Trent Horn: I guess my next question to you then before we get into the evidence for annihilationism and the arguments for and against it, do you think that people, because if you look at Edward Fudge, the thing that motivated Fudge when he … The movie makes a big deal about one of his childhood friends dying and he’s anguished about the thought of this kid being in hell for all eternity. Do you think that sometimes people are, they start with an emotional revulsion to hell that leads them to rethinking this in the Biblical texts or? That’s something that concerns me. Are we looking at the Biblical texts to try to get out of what Keith Parsons calls Christianity’s most damnable doctrine, which is hell, or are we just trying to approach the texts to see what they say?

Trent Horn: Do you see a concern that of emotions driving the horse, I guess? That could happen the other way too. The traditionalists have their emotion of this is the way it’s always been and I’ve got to keep it. What are your thoughts on that?

Randal Rauser: The Stott quote is a great quote. I’m familiar with it. It comes from a book called Evangelical Essentials he wrote with David Edwards and I think that what that quote highlights is the role of moral intuition in human reasoning. I actually don’t think that … I mean our moral intuitions are fallible, just like all of our reasoning generally is fallible, just like our exegesis is fallible, our logic is fallible, but nonetheless, they can provide a good starting point for reflection.

Randal Rauser: So I think one of the problems when we assess the viability of the eternal conscious torment interpretation of scripture is I don’t know if people often really appreciate what the doctrine is proposing and I think we need to have a thick description of what it is proposing in order to sort of draw that reflection that Stott is talking about there. I think it is a pretty horrifying doctrine and we do have a moral revulsion to it, certainly I do.

Trent Horn: Also, I think what comes with hell … I’ll recite here where the catechism teaches on hell, which is actually very brief. So the catechism’s a collection of the teachings of the Catholic church. Of course there have been theologians who have speculated about different aspects of theology, but they’re not binding for us to believe. The catechism summarizes those teachings that we are bound to believe, the teachings of the church. Then I think you and I would agree a lot of people will describe hell in different ways.

Trent Horn: This is what the Catholic church teaches. It says the teaching of the church affirms the existence of hell, this is in paragraph 1035, affirms the existence of hell and its eternity. Immediately after death, the souls of those who die in a state of mortal sin descend into hell where they suffer the punishments of hell, “eternal fire.” The chief punishment of hell is eternal separation from God, in whom alone man can possess the life and happiness for which he was created and for which he longs.

Trent Horn: I think all the parties in the debate seem to agree that the traditional concept of hell at the bare minimum is that it is eternal and unending and that it is hellish, miserable. It is a place one would not want to be. Though I do think what people disagree about the exact nature of the punishments though. What do you think?

Randal Rauser: Well, annihilationists and eternal conscious tormentors … Sometimes I’ve seen the term infernalist used as well, so that’d be a nice one for parity, but they agree that it never ends and that there’s a finality to it. Of course those who are universalists would believe that it is finite and does come to an end. The one thing I would want to highlight is in scripture, Daniel 12:2 is probably the best example, as well as Jesus’ reference in John 5, is that there is this general resurrection to judgment which involves body and soul or body and mind.

Randal Rauser: There is a historic definition in theology of hell that there are two dimensions to it. There is, for eternal conscious torment, there is suffering, the pains of sins and the pains of loss. The pains of sins are the physical sufferings, and the pains of loss are the psychological mental suffering. I think it’s important to appreciate what eternal conscious torment is proposing, is to describe it appropriately as torture because torture involves the severe infliction of mental and or physical anguish on another person as a punitive measure. And that is certainly what is being proposed in eternal conscious torment.

Trent Horn: There is disagreement though about who is doing the torturing though, about whether it is God who is directly causing this, whether the damned torture themselves, or also whether the damned torture each other as well, has been something that’s been proposed. I think people would agree it’s torturous, but there is disagreement about the mechanisms that make it so.

Randal Rauser: But it’s still … First of all, it still is torture, so on … Hell is described in several places, so for example, in Matthew 25:41 and 46, the goats are described as going away into eternal punishment by that translation of the text. It is a punishment that God is punitively overlooking, so whether he actively visits punishment upon them or he pulls back in some sense and allows them to torture themselves, it is still God, the one who is overseeing a punitive torture eternally of these individuals.

Trent Horn: Right. So it’s like … The annihilationists would also have to face this question from an atheist, how could you believe in a god that sends people to hell? Even you as an annihilationist would say, “Well, people send themselves there, though there is a sense in the case that God also sends them there.”

Randal Rauser: Yes, but God, on annihilation isn’t eternally torturing people, that’s the difference. Now in terms of the self-infliction, if I can just give you an analogy. I knew a young lady in high school that she was a cutter and she would sometimes cut herself. One time we actually saw her cutting herself and we physically restrained her from doing that. Even on this sort of milder account of hell where God is not the one actively visiting torture on people, he nonetheless is the one who stands by and allows them to torture themselves, eternally, to an unimaginable degree of physical and mental anguish. I think is that really consistent with who we understand God to be? It’s a fair question and that brings us back to Stott’s concerns.

Trent Horn: Right. And then the reply … I’ve got to get a pithy one worder here. I can’t pick eternalist because that has … I mean, I think I can. It has other concepts dealing with philosophy of time or things like that because the difference between, I’ll do the annihilationists and the endurantist, one who is that the punishment endures. The annihilationists believe that it ends. You’re annihilated.

Trent Horn: We’ll go back to the question when we pick analogies, and I think this will come up in our discussion of when you try to understand hell and you create analogies between punishment, to always make sure they’re one to one and they match up. That there are cases where we restrain people when they harm themselves, when it appears their free will has been compromised, they’re not in a rationally functioning state, but sometimes we also allow people just to go and do things to harm themselves and we respect their freedom in choosing to do that, choosing a very risky lifestyle for themselves, for example.

Trent Horn: Let’s go then, I’ll guess I’ll put it to you, very briefly, why should someone believe in annihilationism, that hell ends with the destruction of the damned and they cease to exist?

Randal Rauser: Why should they believe it?

Trent Horn: Yes.

Randal Rauser: Well, of course, I think that there are these good reasons born of moral intuition and reflection. I’d also like to … We should obviously come to scripture in a moment, but there’s another part of here as well and that is the relationship between those that are resurrected on the eternalist view to eternal torture and those who exist forever in heaven. So of course in heaven, we know Revelation 21:4 that there’s no longer any mourning or crying. Every tear’s been wiped away. Am I to consider that possibly every tear’s been wiped away and I’m being comforted eternally in heaven and my daughter has been resurrected and is being tortured forever unimaginably whether by God or self-inflicted in hell?

Randal Rauser: What does that mean for what it means to be me as someone fully formed to Christ and I think it’s a fair question. It’s very hard to make sense of that. People like Aquinas and many others, [tortollean 00:18:07] famous leader, infamously, Jonathan Edwards have all argued that in fact the suffering and pain and anguish of people in hell further-

Trent Horn: The pleasures of the saved.

Randal Rauser: … deepens the pleasures of … Yeah, because maybe something of the contrast effect. We see God’s justice and wrath visited upon them. I just think that’s hard to understand.

Trent Horn: Well I think that view can be misunderstood into thinking that the saved, the pleasure they derive is some kind of glee at the punishment over the damned. Where I think that when you read Aquinas and what he says on that, the pleasure that comes is almost like a sense of gratitude or relief, in the sense that imagine if you were in a situation where a doctor was freely offering a cure to a terrible disease and you were a person who chose to accept it and you saw others who did not, you would feel bad for them, but you would also feel a sense of relief like, “Oh, I’m so glad that that did not happen to me.”

Trent Horn: I guess this is one objection. There’s two ways we can go about defending annhilationism. One would be our moral intuitions do not allow for eternal conscious torment, so it could be a strictly even moral or philosophical argument. Although that’s really more of an argument against eternal conscious torment more than annhilation because if you take away eternal conscious torment, you still have the question … A lot of people would say a loving God would just … You would be a universalist and everyone’s redeemed. There, you would probably bring into the Biblical arguments next, which is what does the Bible say about our final fate?

Trent Horn: I think the reason you describe your self as a hopeful universalist, you’re not totally sold. It’d be great if it’s true and just for our listeners so they’re caught up, universalism would be the idea of the form we’re talking about, is that some people go to hell, but it’s finite. They’ll be punished there and then it’s almost like purgatory a little bit. Then they will be in heaven for all eternity. So hell is finite in that view. Your view, the finite nature of hell ends with annhilation. The universalist views that it ends with heaven. You don’t agree to that view, or at least you’re not sold on it.

Randal Rauser: No. So we do, if we go to scripture, we have certain texts which seem to support eternal conscious torment. I think we have certain texts that seem to support annhilation, and we have some texts that seem to support the universal restoration of creation and of all creatures. Each of us finds ourselves choosing, or finding ourselves gravitating toward one set of those texts as control texts, through which we interpret the other ones. So as an annihilationist, I tend to go for the ones that suggest annhilation or destruction, the cessation of existence, the finality of existence.

Trent Horn: So are you saying that those texts … So for you, because some of our listeners might be a bit baffled. How could someone … Isn’t the Bible very clear on this? From my reading of annhilationism, annihilationists seem to take the view that when scripture talks about and Jesus talks about the destruction, the death of the damned, they will be destroyed, apollumi, destroyed. They will perish. God does not want anyone to perish. That those words refer or have a closer analog to when things are destroyed or perish in this life, they cease to be. So you take that the annihilationists’ texts are those texts that say the damned will be destroyed or they will perish. It just means they will cease to be. Is that …

Randal Rauser: Certainly that’s a reasonable interpretation of those passages that talk about death and destruction. Matthew 10:28, for example, so-

Trent Horn: Do not fear the one who can kill the body, it uses the Greek word for kill, fear the one who can destroy, apollumi, body and soul-

Randal Rauser: In hell-

Trent Horn: … in hell. Right. Matthew 10:28. I think for me … So it’s important. It sounds like in this conversation we’re going to be juggling two different ways of coming to understand whether annhilationism is true, whether the damned are just destroyed. Moral, philosophy, and ethics, and then Biblical hermeneutics, what does the Bible say. It sounds like you believe that our moral intuitions should guide our Biblical hermeneutic and I would agree with you on that point, certainly, but how do you see the two interplaying?

Randal Rauser: Well, I actually think there’s a little more. I think tradition as well, so reading traditions that we come to the texts through those traditions. We grant some prima facie value to those traditions to guide us hermeneutically and then our own reading of the text, our own rational reflection and argument, and our own moral intuitions and moral reasoning. I think those are all things that we bring to the text and so based upon that, yeah, I’d bring all this together. I try to understand does this picture of hell with God possibly resurrecting my daughter to eternal torture make sense? Does it make sense and I recognize that you said, “Well, maybe I would have just this sort of satisfaction that it was not me, but my daughter that was in hell and I was in heaven.”

Trent Horn: That would be part of it.

Randal Rauser: Yes, but even that, I would just want to push back and said that you’d still … You mentioned that well there’d be sadness for what happened to my daughter, but that doesn’t seem to be consistent with Revelation 21:4.

Trent Horn: That’s where, for me, when we take … So I think Revelation’s a good book to go for here what it talks about heaven and what it talks about for hell, that this objection, this would be more of a … It’s a combination of a moral intuition, but also Biblical objection that if the Bible says there will not be sadness in heaven and it seems quite obvious I will be sad at the idea of loved ones being in hell for eternity, it would follow that loved ones would not be in hell for eternity. Then the traditionalists or the endurantists would challenge the premise that those who are saved in heaven would experience a sadness or a reduction in their happiness over that.

Trent Horn: One thing that, and I don’t know if you wrote this or someone else, I tried to find it before our episode, the concept that if I knew that my child was being tortured by a serial killer in a cabin somewhere, how could I ever have rest or happiness in this life? But I’m very skeptical of those kinds of analogies because the issue of justice doesn’t come into play, so I might say, “Well, could I be happy?” I think of people who have loved ones who have been incarcerated for horrible crimes, so what if, not that your child’s a victim of a serial killer somewhere, but your child was the serial killer and now they have been incarcerated, so they are receiving a just punishment.

Trent Horn: I think for a lot of people, there’s a different set of feelings that mostly, it’s a sense of embarrassment over the idea that I’m related to someone who did this horrible crime. That’s more of the concern that when we’re in heaven, our views of sin will be very different and those who have chosen to reject God, they may be in a different light. They may not be just that regular pleasant person we knew here on earth. Their full rebellion will become known and we won’t balk at the idea of justice being meted out. I think the analogy might break down there.

Randal Rauser: Yeah, obviously if eternal conscious torment is true and my daughter is resurrected outside Christ and she ends up being tormented forever, then it’s just by definition. Then I should take satisfaction in that fact. The question is, nonetheless, just to come back to our moral intuitions, and then maybe we should segue more to some of the scriptures more fully.

Trent Horn: Yeah, sure.

Randal Rauser: But I still think we’re at the point of saying, but does it make sense that I would only have satisfaction in the visitation of God’s justice and no lament for this child that I had lost? That now, it’s still my same child that has been resurrected and is now suffering forever. I think as a parent, I don’t think that my moral intuition is being clouded at this point. I think, actually, because of the intimate love I have for my daughter and connection I have to my daughter, that it provides a greater moral clarity for understanding the nature of what is being proposed in eternal conscious torment.

Trent Horn: But I would be concerned about mapping the love and intimacy of our personal relationships on earth to what we will experience in heaven and the relationship we’ll have with God there because Saint Paul says, “Now we see in a mirror dimly, then we shall clearly.” That many times, emotionally, we experience greater emotions in the presence of our loved ones here on our earth and the emotions we feel with our relationship with God are somewhat muted. But then, in heaven, it may be that our apprehension or the beatific vision, an apprehension of who God is will be so much more.

Trent Horn: I feel like sometimes in trying to pray and have a relationship with God here on earth, in compared to the powerful emotions we have with our loved ones, it’s like the firefly versus the spotlight. But in heaven, if God is like this infinite nuclear bomb of glory that we’re attracted to, that might change our understanding of the bonds we have with our other loved ones.

Trent Horn: Did you ever read The Great Divorce by C.S. Lewis?

Randal Rauser: Yes.

Trent Horn: So you remember there was a scene where there was a woman who ends up in hell because she just can’t possibly let go of, I think her son who is there or … That kind of stuff brings me back to what Jesus said, “Whoever does not love … Who loves his father or brother or sister more than me is not worthy of me.” That would be a concern that I would have, especially in these … the objection. So it’s funny, the objection here is not so much the eternal conscious torment of anybody, but especially of someone I really care about.

Randal Rauser: No, I would push back on that. It’s not especially about somebody I care about, but rather the people I care about illumes to me the depth of the problem. Now, so your response here said well God’s light is going to kind of overwhelm the light of these lesser creatures that are suffering. I think it’s actually quite the opposite, that the more we love God, the more we love other creatures, the more we have an awareness of the needs of other creatures. I don’t know why that would suddenly click off when we got to eternity that I would no longer be concerned with the suffering of my daughter as a little flickering light because of the sun of God. I think it’d be something quite different than that.

Trent Horn: Well I think that when it comes to concern, I think that once we have a perfect understanding of whether something is just or not, and I will come back to the question, is this just or not and if God has decreed it to be so, then it is. Then I think we’ll see that a problem we deal with in this life is that we don’t have the same revulsion to sin and understanding of holiness that we will once we’re freed from the bonds of what this world does to us.

Trent Horn: You mentioned Revelation about wiping away every tear and the language there. That brings me back also to Revelation’s depictions of hell and I think we have enough time. Let’s round us out then. We’ve introduced people to the moral intuition and philosophy and we can talk about scripture a little bit on this. That for me, the hard time I have with annihilationism is this: I agree with you there’s Matthew 10:28, there are some texts that can be read in an annihilationist way. There are other texts, Matthew 25:46, Jesus says, “They will go away into eternal life and the wicked will go away to eternal punishment,” seem prima facie to be an eternalist or unending in their reading.

Trent Horn: The difficult time I have is this, that I think I have an easier time taking the “annihilationist” texts, they’re not as problematic to my view because I can say that terms like perish or destroy make just as much sense when they refer to eternal conscious torment that you’d say that someone who ends up in this way, people will say even if you go bankrupt today, like, “Oh, I’ve been destroyed. My life is ruined.” We’d say someone who goes to hell is perishing. That in the Greek of Jesus’ time, there’s not a … We have the word damnation. We have a single word to describe eternal conscious torment. I’m not familiar with a single word like that in the New Testament. I don’t know if you are. There’s just a single word or verb to describe the concept of eternal conscious torment.

Randal Rauser: Yeah, I’m not familiar with that.

Trent Horn: So since there isn’t a word like that. We have damnation, then it would make sense to me using other words like destroy, perish-

Randal Rauser: Or it could also make sense to conclude that that concept isn’t in the New Testament.

Trent Horn: Well, one could, yeah, you could say the word’s not used because it’s not in there. My point is, I feel I can read the annhilationists’ texts under my view. It’s the endurantists’ text I have a hard time with the annihilationists’ exegesis of them. That I think is more problematic for that view. So for example, in Revelation 14:11 and Revelation 20, when it talks about … I’ll bring it up.

Randal Rauser: Revelation 14, the smoke of their torment rising forever.

Trent Horn: Yeah, and then … Yeah, so we’ll start. There’s that, coupled with Jesus talking about punishment being eternal and then the other. Well, I don’t want to stack too many things on you. We can start with that and then I have other concerns.

Randal Rauser: Yeah, so Matthew 25:41 and 46, Augustin was one who famously said that there is a parody here, so if the one goes on, it is eternal life forever. The other one goes on and is eternal punishment forever. Well, Stott, among many others, have responded to that, and I think they’ve made a fair point, is to say as much as there is comparison here, there is also contrast. So the comparison is that these are ongoing. If this new condition is initiated, then you never go back from it. It has a finality to it. There is a final state of eternal life and a final state of eternal punishment.

Randal Rauser: However, there is also as much contrast as comparison. So the contrast comes in in terms of punishment, that it does in fact result in destruction, that there’s no coming back after it. But I would also say for our universalists in the room, that there is a universalist reading of Matthew 25: 41 and 46 because [foreign language 00:32:42], the Greek adjective there, can just mean an extended period of time. We get the English word eon from that and so it could mean that there’s a comparison here that prior to the final state, this is a penultimate state where some people go on to eternal life and other people go on to punishment, and prior to the completion of that when God is ultimately all in all.

Randal Rauser: The point I’m making there is that, yes, I think in the vast majority of these cases, there are certain texts that are more reasonably at face value, perhaps, interpreted in a particular way, but are fully reconciled with the other positions, I mean your control texts.

Trent Horn: I guess for me, that we also have to be … There’s a danger here in saying, “Well this group does propose this and this group does propose this,” merely because a viewer interpretation is proposed doesn’t garner that it’s plausible because in Proverbs says the first who makes his case seems right until another comes forward to challenge. For example here, in Matthew 25:46, the annihilationists’ case would make a lot more sense to me if, to make the compare and contrast, is if Jesus said they will go away into eternal death, but the righteous into eternal life. That would make a lot more sense to me. But to me at least, the plain reading, it seems to be they will go away into eternal punishment, but the righteous into eternal life. Life is something that will be had, [foreign language 00:34:08], eternally or an unending way, and punishment is something that will be had.

Trent Horn: I know people can interpret it in different ways, but what’s driving it, I guess? What’s your response to-

Randal Rauser: Revelation 14?

Trent Horn: Yeah and Revelation 20.

Randal Rauser: It’s okay. So Revelation 14, it says the smoke of the torment rising forever and ever. First thing I would just say is this is, let’s be cautious that this is apocalyptic language and apocalyptic text-

Trent Horn: But we have to remember that the argument you made earlier against eternal conscious torment relies on … Because one could respond when you said, “Well they’ll wipe away every tear. There’ll be no sadness.” I’ll say, “Well, it’s apocalyptic. It’s poetic.” And that’s one way to look at it, but I think it also does really describe things that are happening, if not in every literal detail.

Randal Rauser: Sure. Yeah, fair enough. So the smoke is rising, but I would say the smoke of Sodom and Gomorrah is also described as rising forever and of course it’s not literally rising forever, so there, the reference is to a finality of the judgment in the Old Testament and here I think the reference is to the finality of the judgment.

Trent Horn: I’ve heard this response also. I mean this is … Fudge and others, I think, come with this that because the language here comes from the Old Testament, making these different references, that it’s the same language that was used to describe the final fate of Sodom and Gomorrah, that because of course Sodom and Gomorrah do not experience that forever, it doesn’t apply here. The hard thing for me when I hear that and just read the passage and it talks about hell in this powerful way, that the smoke of their torment goes up ever and ever and they have no rest day or night, these worshipers of the beast in its image.

Trent Horn: I am concerned that if we limit the New Testament, that if meaning of New Testament passages has to be constrained in every detail to an Old Testament text that they refer to, if they’re using language from the Old Testament to make their point, I’m worried that we’ve put a straight jacket around it. That well, it can’t … Because then, what about … What do we do with those Old Testament passage … Would the New Testament descriptions of Jesus and prophecies that reference Old Testament passages that don’t … You can’t … Because Isaiah 7:14 is probably about King Hezekiah. It’s not about literally about Jesus or the famous one in Hosea, out of Egypt I called my son. Well, that can’t really refer to Jesus because in the Old Testament it only meant this.

Trent Horn: Do you see the concern there about taking the New Testament descriptions and limiting them too much if they refer to the old in this context about describing hell?

Randal Rauser: Yeah, sure. I would just say that I’m not using this as a straight jacket. I’m just saying that there is already a precedent in the Old Testament for a prophetic, hyperbolic language of smoke rising forever and ever, which is not literal, but in fact should be interpreted as a hyperbole emphasizing the finality of the judgment. But I’m not saying that this always has to be the case, but if we have a precedent to interpret in a particular way and that helps us to avoid the idea, the proposal that God resurrects people to torture them eternally, then I think that’s a good reason to consider this reading.

Trent Horn: I think we’ve come … I’ll keep it to one episode, I think, because I think we’ve come down to the crux. I think we’ve covered a lot of ground here and obviously both of us are firmly committed in our views. It would be naïve for a listener to think like, “Oh, I wonder who’s going to change their mind at the end of this one?” It’s, well, I think the importance here is to be able to explain our different perspectives and what we have on these different issues for people to be able to learn and understand.

Trent Horn: Do you have any last thoughts on this for people to consider when it comes to the question of annihilationism?

Randal Rauser: I could say something about Revelation 20 as well, but I think in conclusion, I’ll just say that this issue, when I talk to atheists and people who have left the church, this is probably the number one theological issue that gets raised in terms of an objection to Christianity, how could God allow acts with respect to eternal conscious torment? I think from an apologetic perspective, it is important to recognize that there are minority witnesses in the history of the church that have allowed for these alternative perspectives and that this should not be a moral revulsion to the proposal that God resurrects people to eternal torture. It should not be the grounds under which somebody leaves the church, ever, because there are alternative readings of these texts that are well established in the Christian tradition. We should be careful about creating more stumbling blocks than need to be for people to be joining the church.

Trent Horn: My concern then, to wrap up my concern with this, that if, of course God taught that the damned were annihilated or destroyed, then yeah, I think that would certainly be a lot more palatable for many people and it would remove … I would still think there would be some kind of horrors involved with hell, just the same as many people, secular individuals experience a revulsion to capital punishment. That there is a certain horror involved with someone going out of existence forever, but I believe less so than eternal conscious torment.

Trent Horn: However, I still think that when it comes to the afterlife, when it comes to what God has in store for us after this life, we have to take at face value what He says and is revealed to us there. I would just be concerned about keeping that at the forefront in our discussions to be able to move forward on this topic and also to make that there’s other secondary concerns. There is the concern about those who leave the church over objections to eternal conscious torment. My secondary concern would be those who believe that missions and evangelism are not as important because they find annhilationism more comforting in that regard. So I think that secondary concerns can always drive us in incorrect directions. Instead, we should use sound moral, philosophical, and Biblical reasoning and try to arrive at the truth and we just have to keep doing that in these issues, I guess, right?

Randal Rauser: Yeah. I think I have provided, or certainly I think others have provided a reasonable case for annihilationism. In terms of the missional impulse that you described, that’s a good example. Paul says in Romans when he talks about by being saved by grace, so should we sin so that grace may increase? By no means, but somebody could have argued that. But look at what will happen if we talk about preaching by saved by grace alone is that people may be undermined. The Pelagian Gospel would be more effective at getting people to do the right thing, that wouldn’t make it true, right?

Trent Horn: Yeah, we should be wary of misconceptions, but not let them drive what the truth is.

Randal Rauser: Yes.

Trent Horn: All righty. Randal, thank you so much and looking forward to having you on for other good discussions, so thanks for being here on the Counsel of Trent.

Randal Rauser: Thanks for having me Trent.

Speaker 1: If you liked today’s episode, become a premium subscriber at our Patreon page and get access to member only content. For more information, visit trenthornpodcast.com.