In Robert Speaight’s The Unbroken Heart, a sadly neglected novel among readers whose tastes run to the literary lite, a character by the name of Arnaldo has just been told of his beloved wife’s untimely death. His reaction, by the standards of the day, seems very strange indeed. “It does not really interest me,” he announces, “to know by what accident Rhoda died. All our lives are an accident and we must all die somehow.”

So what, the astonished reader is moved to ask, does interest him? In a statement almost incomprehensible to modern sensibility, he replies: “I want to know how she died, what was in her mind, what her soul said to God when she fell from the rampart. Nothing else is of the least importance whatsoever. Our life is directed to that moment when we fall from the rampart, and our eternal destiny is decided by it. But I see that you don’t believe that.”

Nor, for that matter, does anyone else. A revolution in sensibility having set in, uprooting the entire eschatological horizon, there an absence of interest in the soul’s immediate destiny. Not only that, but for vast numbers of people the fact that virtually all souls go straight to heaven anyway, there to enjoy forever the identical joys they experienced in the flesh, there can hardly be much point in worrying about hell.

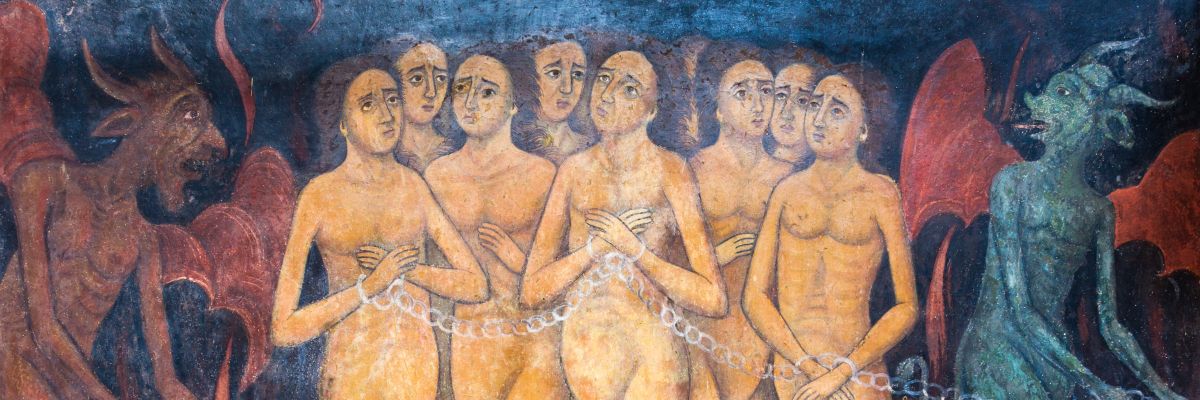

Does anyone actually go to hell anymore? I mean, leaving aside the usual suspects—Hitler, Stalin, Pol Pot, and (just as soon as we can conveniently dispatch him) Osama bin Laden—is there a sufficient number of reprobates around even to justify the existence of such a place? And, really, just how wicked does one have to be to qualify? Surely it is not even thinkable that good, respectable Catholics might take themselves there. What are we to make of hell? More to the point, what does the Church make of hell?

In contrast to the mincing multitude unwilling to countenance anyone going to hell, least of all regular churchgoers, the position of the Catholic Church is refreshingly emphatic: There is not anyone, be he the most exalted churchman anywhere in Christendom, who is not at liberty to take himself straight to hell. Where, for the sake of even one mortal sin committed against God, he shall languish forever in the most unimaginably hellish torment.

“Mortal sin,” we are told, “is a radical possibility of human freedom. . . . If it is not redeemed by repentance and God’s forgiveness, it causes exclusion from Christ’s kingdom and the eternal death of hell, for our freedom has the power to make choices forever, with no turning back” (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1861).

In every life, however brief its duration, the essential drama of human existence unfolds against an absolute horizon beckoning each of us to one or another eternal possibility. To be thus poised, moreover, between the hope of heaven and the fear of hell, terrifyingly free to choose one or the other, is a very good and salutary thing. As Dr. Samuel Johnson famously said about the prospect of being hanged, it wonderfully concentrates the mind.

It is terribly wrong to so trivialize man’s dignity that in this most awesome discharge of human freedom, in which the human person decides for or against God forever, the full seriousness of what may be undertaken is treated as mere child’s play. How otherwise can we expect our freedom to be respected if God will not honor our right to throw it away? A human liberty that does not include the right to say no to God—yes, even to the point of rejecting his invitation to love forever—is no liberty at all.

Indeed, one could almost define man as a being free to break the umbilical cord with Being himself, burning his last bridge to God. Only man possesses so radical a liberty that it can choose—yielding, God knows how, to what pressure of perversity—its own annihilation. And the temptation to do so stalks even the most self-respecting Catholics. “For sweetest things turn sourest by their deeds / Lilies that fester smell far worse than weeds,” as Shakespeare said (Sonnet 94). This being so, it is the good Catholic especially who will guard against an impacted self-complacence. The corruption of the best, it has wisely been said, is the worst corruption of all.

It is this fear especially that threatens to unhinge the heart and soul of the old man portrayed in John Henry Newman’s dramatic poem “The Dream of Gerontius,” a masterpiece of lyric beauty and lucidity written in 1865. The story depicts the journey of a soul to God at the very hour of his death. Who, despite all the recollected powers of his soul, fruit of a lifetime steeped in habits of Catholic piety, despite even the presence of dear friends eager to offer up prayers and petitions to help navigate his way home to God, remains deeply afraid. Afraid of what? That God, seeing the real truth of his inner life, the radical poverty, the desperate dependence upon grace, may yet refuse to admit him into the Company of the Elect, the joy of unending Paradise.

And so, moved to charity, the Assistants take up the chant, repeatedly imploring God to show mercy, to impart that virtue of final perseverance of which we all stand in need, particularly those of us inclined to take salvation for granted. “Be merciful, be gracious,” they ask. “Lord, deliver him

“From the sins that are past;

From Thy frown and Thine ire;

From the perils of dying;

From any complying

With sin, or denying

His God, or relying

On self, at the last . . .”

The invocations continue in the same rhythmic, resonant way until, finally, the Priest, marshaling all the forces of heaven, urges the dying Gerontius to “Go forth upon thy journey, Christian soul!

“Go from this world! Go, in the name of God

The omnipotent Father, who created thee!

Go, in the name of Jesus Christ, our Lord,

Son of the living God, who bled for thee!

Go, in the Name of the Holy Spirit, who

Hath been poured out on thee!”

What a stirring send-off to accompany the soul to God! And when at length the moment of blessed release comes, it is no less the Angel Guardian who announces the work is done, “For the crown is won . . .

“My Father gave

In charge to me

This child of earth

E’en from its birth,

To serve and save,

Alleluia,

And saved is he.”

This is not only the basic formula for how we Catholics are to die but also to live. Under the Mercy. For if ever salvation depended on you or I, the spectacle of the merely human propelling itself along some purely promethean highway to heaven, the place would be empty. To remain faithfully Catholic, therefore, right up to the end, is to live and die always as the recipient of a blessing one could never oneself give. And then to try and pass it along to others in the spirit of the mendicant whose lively sense of gratitude for the very little that he has moves him to share it with others. Unlike “the calculatingly righteous man,” whom Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger has described in his profound Introduction To Christianity (a wonderful book on which I first cut my theological teeth), who “thinks he can keep his own shirt-front clean and build himself up inside it.” Beneath the weight of such sanctimony, the self-satisfied will sink into an abyss of unrighteousness.

Should this not be the omnipresent fear and danger facing the so-called good Catholic? That knowing how much easier it may prove for grace to move the pagan that the prig, he refuses to preen himself on the least show of virtue. “Righteousness,” we are reminded, “can only be attained by abandoning one’s own claims and being generous to God. It is the righteousness of ‘Forgive, as we have forgiven’ . . . it consists in continuing to forgive, since man lives essentially on the forgiveness he has received himself.”

It is to sear upon the memory the words of the apostle James, who warns us that God’s “judgment is without mercy to one who has shown no mercy” (Jas. 2:13). For you and I to suffer such exclusion from God’s kingdom, it does not follow that our sins be satanic in any sort of grand and gaudy way, as if we’d taken out first-class accommodations on an express train bound for hell. Hell is not, as the holy curate in Bernanos’ Diary of a Country Priest informs the old woman whose soul stands in the gravest peril of going there, like anything we might imagine in this world. We may judge it by the standards of this world, but to do so is a terrible mistake, for it is of the other world that only the exercise of charity prevents our falling into. “Hell is not to love any more, Madame. Not to love anymore!”

Who among us is not well advised, therefore, always to be mindful lest our poor show of love fall dangerously short of even the most minimal expectation Christ sets for those who claim to love God?