It was a soaking wet night and a bitterly cold journey for the stagecoach travelers, especially those in the cheap seats outside, with the wind howling and the rain lashing against their faces.

This was Oxfordshire, England, in October 1845, at the height of Queen Victoria’s reign. Abroad, Britain was regarded as a world power, her prestige enormous, her armies triumphant, her influence spreading in the scramble for Africa and the sea lanes of the globe. But at home, many people lived simple, humble, hardworking lives—and many were in poverty.

Certainly none was poorer than the shabbily-dressed priest who alighted at a row of cottages in the village of Littlemore, just outside Oxford. He was Father Dominic Barberi, and he had come at the invitation of the Rev. John Henry Newman, who knew that he was traveling through the neighborhood and had asked that he stop at Littlemore. Father Barberi was Italian and spoke English with a heavy accent. He was a Passionist priest and wore the habit of his order, with its badge showing Christ’s heart surrounded by a crown of thorns.

Catholics had achieved freedom in Britain just a decade and a half earlier with the passing of the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829, which ended three centuries of persecution. Although increasing numbers of Catholic priests were to be seen, and Catholic churches were being built in towns and cities, a Passionist in full-length black robe and sandals was not a familiar sight in the English countryside. The priest had come to England on a mission, fired by a longing to see England restored to full Catholic unity. He struggled to learn to speak English, yet seemed to reach people’s hearts and had won many converts. In Newman’s house, Fr. Dominic stood by the glowing fire, grateful for its warmth.

Will You Hear My Confession?

As he dried his cape, the door opened. A figure entered and knelt at his feet. It was John Henry Newman: one of England’s most distinguished minds, a preacher who fired all of Oxford with his masterly sermons, a luminary of the Anglican Church, a brilliant writer, a public figure whose work was discussed in dining rooms and debating halls across the land. There in the firelight, Newman asked to be received into the Catholic Church and begged Fr. Dominic to hear his confession.

It is one of the great scenes of English Catholic history, along with St. Thomas More on the scaffold at the Tower of London and St. Edmund Campion being hauled through mud and filth to be hung, drawn, and quartered at Tyburn, down through the years of loneliness, contempt and struggle in which Catholic families sought to maintain their faith despite laws designed to eradicate it, a new chapter had just opened. It was fitting that it would have its share of sorrow, hardship, and disappointment.

John Henry Newman was born into a moderately prosperous family at Grey Court House in Richmond, Surrey, was educated at Oxford University, and was ordained into the Church of England. His religious beliefs had been deeply influenced by Evangelical teachers and writers, but as he studied more deeply and read the Church Fathers, he came to a richer and more profound understanding of what is meant by “the Church” and its place in salvation.

It is impossible to overestimate Newman’s influence on the Anglican Church. His hymn, “Lead Kindly Light,” is still widely sung, and he was a central figure in the standardization of many practices formerly deemed “high church.” He sought to discover the true Church: he saw in Anglicanism something that had authentic roots and could trace its history to the Apostles with an unbroken, albeit damaged, lineage that ensured a sacramental system. He tried to prove this by reference to the traditions of the early Church, and by exploring the full meaning of episcopacy, priestly orders, and the nature of Church authority. In the end, his studies led him inexorably to the Catholic Church. In his journey, he carried aloft a “kindly light” that was to illuminate many others, and continues to do so.

Am I the Queen or Not?

Today, when the Church of England ordains women, discusses homosexual marriage as if they were an open question, accepts artificial contraception, and fails to oppose practices such as abortion or the use of pornographic material in children’s sex education, it would seem logical for a devout Anglican to jump ship and head for Rome. But it was not like that in the nineteenth century. It took an extraordinarily agile mind to dissect the reality of the Anglican ecclesial claims and to recognize that the fullness of what Christ had meant by “Church” was to be found only under the guardianship of the successor of St. Peter in Rome.

Rome! To an educated Englishman, it was a magnificent city, the center of the classical world with which he was familiar from school. But to suggest that the Italian prelate occupying the Papal throne had claims on the loyalty of Englishmen seemed preposterous in the middle of the nineteenth century. When John Henry Newman had already been a Catholic some years, Queen Victoria is said to have exclaimed, “Am I Queen of England, or am I not?” when she learned that a hierarchy of Catholic bishops was to be re-established in her land, and that this had been announced from Rome.

For common people of England, it was probably enough to invite derision that most Catholics were foreigners or that many of them were Irish. To the better read and more widely educated, the idea that Catholics should be tolerated and treated fairly was gaining ground, and was seen as something granted by a magnanimous Protestant nation that could afford to allow a moderate degree of absurdity and even dissent.

Still Newman’s conversion produced a firestorm, and rumors abounded about the reason for his decision. To answer one of his major critics, the author Charles Kingsley, Newman produced his Apologia Pro Vita Sua, describing in detail the full development of his religious ideas and convictions and explaining how they had led to his Catholicism. It became a classic work of spirituality.

“There are but two alternatives, the way to Rome, and the way to Atheism: Anglicanism is the halfway house on the one side and and Liberalism is the halfway house on the other…” He knew that in his earlier attempts to shore up the Anglican position, he had made it the more attractive and plausible to many. Now he seemed to be undoing that good, and defecting to a place where few would follow. Newman’s decision, which culminated in his humble gesture before Fr. Dominic, caused him much anguish.

Goodbye, Beloved Oxford

Nor was his path easy, humanly speaking, once he became a Catholic. A layman again, he could no longer use his undoubted gifts in the profession for which he had been trained. As vicar of the University church, he had preached to capacity congregations, and at Littlemore, he had created a rural retreat where he lived in simplicity. Now he was to leave even this modest haven. There was a sorrow in leaving Oxford.

I called on Dr. Ogle, one of my very oldest friends, for he was my private Tutor, when I was an Undergraduate. In him I took leave of my first college, Trinity, which was so dear to me, and which held on its foundation so many who had been kind to me both when I was a boy, and all through my Oxford life. Trinity had never been unkind to me. There used to be much snap-dragon growing on the walls opposite my freshman’s rooms there, and I had for years taken it as the emblem of my own residence even unto death in my University. On the morning of the twenty-third I left the Observatory. I have never seen Oxford since, excepting its spires, as they are seen from the railway.

Newman was eventually ordained a Catholic priest and founded (or re-founded, for its owes it origins to St. Philip Neri) the Oratorian order, becoming the father of a community in Birmingham, the initiator of a school that still flourishes, the author of much superb writing and, eventually, a cardinal. There was no shortage of struggle, sorrow, and difficulty in his life—complications in his relationships with the Catholic bishops, exhaustion in trying to establish the Catholic University of Ireland, a libel suit after describing the appalling actions of a serial predator on women who was also a famous anti-Catholic preacher.

But he nurtured souls, instructed, guided, helped, consoled, and inspired. He understood people’s difficulties, listened to their problems, offered wise counsel, explained the truths of the faith, and led many on the right path. He showed the value of seeking truth, and revealed the Church not as an institution to be feared or resented but as a focus of love through which blessings flowed. He made holiness accessible and showed that human minds were designed to seek God, and that intellectual life should have a purpose.

“Our Cardinal”

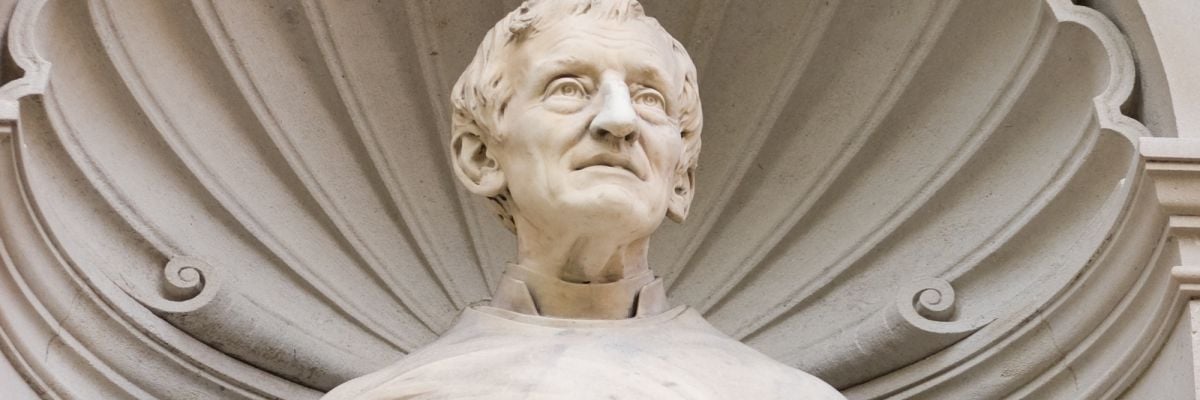

Newman’s works are still read today, his example followed, his heritage honored. The Birmingham Oratory is filled at Sunday Mass. A bust of Newman gazes out at the London traffic outside London’s Brompton Oratory. Periodically, his glorious “Dream of Gerontius” is presented by a full choir at the Royal Albert Hall or the Barbican Centre and new audiences thrill to the beauty of his words. The hymn “Praise to the Holiest” survived the wholesale abandonment of hymnology in the 1970s.

Every English-speaking Catholic owes an incalculable debt to John Henry Newman. My own family is an example: my grandfather converted partly through reading Newman’s works in the 1920s, and my husband’s conversion in Australia in the late 1970s also came via Newman’s books.

Newman’s cause for canonization is now before Rome. As an Anglican, he had been a good pastor and sought to bring people close to God; as a Catholic, this became even more the center of his life’s work. His biographer, Meriol Trevor, wrote:

Newman was loved in Littlemore—no picture village, but something of a rural slum. It is significant that it was for spiritual help that he was remembered there, not for social benefits. It was the same in Birmingham. When Newman’s cause was opened a few years ago, descendants of parishioners, scattered across the world, wrote to recall the love of parents and grandparents for “our Cardinal.” They thought him a saint and kept pieces of his clothes as relics. Today, when those who work for better social conditions are highly praised, it should not be forgotten that in what condition we live, we still need spiritual care, as persons.

The house at Littlemore is now a shrine. Fr. Dominic has been honored by the Church and is now Blessed Dominic Barberi. The Holy Father is known to love Newman’s work. In fact, quotations from the great Englishman adorn the new Catechism, which was collated by the great German theologian and published by John Paul II.

Today, the Catholic Church in England suffers as it does everywhere from dissent and confusion, but it draws strength from its heritage of saints and heroes who were not afraid to proclaim the truth and follow the path of conscience to the fullness of Christ’s teaching.

In “The Power of the Cross,” Newman said:

I will never have faith in riches, rank, power or reputation. I will never set my heart on worldly success or on worldly advantages. I will never wish for what men call the prizes of life. I will ever, with thy grace, make much of those who are despised or neglected, honor the poor, revere the suffering, and admire and venerate Thy saints and confessors, and take my part with them in spite of the world.”