Historically, the Church has taught that the graces of baptism can be received not only through the administration of the sacrament itself (baptism of water) but also through the desire for the sacrament (baptism of desire) or through martyrdom for Christ (baptism of blood).

Recent doctrinal development has made clear that it is possible for one to receive baptism of desire by an implicit desire. This is the principle that makes it possible for non-Christians to be saved. If they are genuinely committed to seeking and living by the truth, then they are implicitly committed to seeking Jesus Christ and living by his commands; they just don’t know that he is the Truth they’re seeking (cf. John 14:6).

In the last century, this has been denied by certain radical traditionalists—for instance, the followers of Fr. Leonard Feeney, or “Feeneyites,” as they are sometimes called. They deny not only that one can be saved through baptism by implicit desire, they also deny that one can be saved by baptism of desire at all.

The pretext for holding this belief consists of certain statements made by medieval popes and councils emphasizing the doctrine of extra ecclesiam nulla sallus (“outside the Church, no salvation”).

With this doctrine as a starting point, radical traditionalists use a simple chain of reasoning: No one outside the Church is saved. All unbaptized persons are outside the Church. Therefore, no unbaptized person is saved.

The problem with the argument is its second premise—that all unbaptized persons are outside the Church. It is true that baptism is required for full incorporation into the Church (CCC 837), but it is not true that all of the unbaptized are unlinked in any way with the Church.

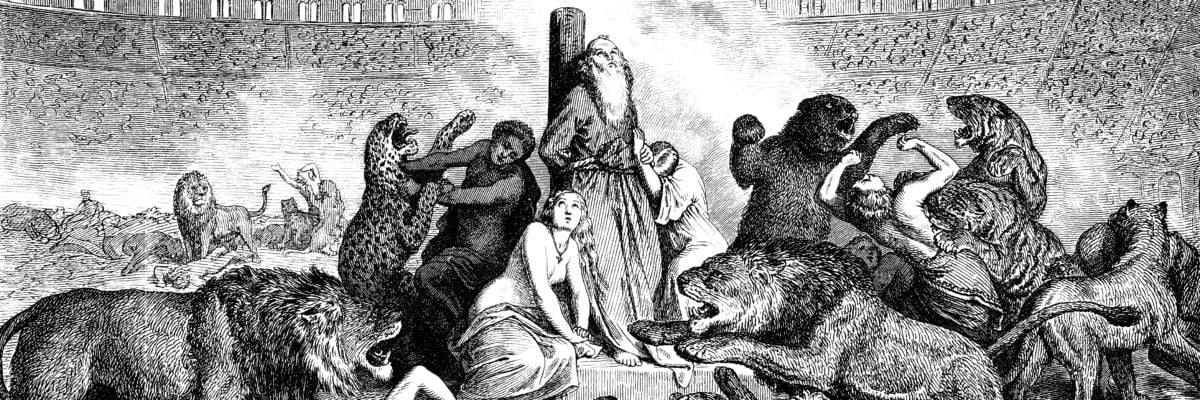

This is something the Church has always been aware of. For example, in A.D. 256, Cyprian of Carthage stated of catechumens who are martyred before baptism, “They certainly are not deprived of the sacrament of baptism who are baptized with the most glorious and greatest baptism of blood, concerning which the Lord also said that he had ‘another baptism to be baptized with’ (Luke 12:50)” (Letters 72 [73]:22).

Likewise, in the thirteenth century, and in response to the question whether a man can be saved without baptism, Thomas Aquinas replied: “I answer that the sacrament of baptism may be wanting to someone in two ways. First, both in reality and in desire; as is the case with those who neither are baptized nor wish to be baptized; which clearly indicates contempt of the sacrament in regard to those who have the use of free will. Consequently, those to whom baptism is wanting thus cannot obtain salvation; since neither sacramentally nor mentally are they incorporated in Christ, through whom alone can salvation be obtained.

“Secondly, the sacrament of baptism may be wanting to anyone in reality but not in desire; for instance, when a man wishes to be baptized but by some ill chance he is forestalled by death before receiving baptism. And such a man can obtain salvation without being actually baptized, on account of his desire for baptism, which desire is the outcome of faith that works by charity, whereby God, whose power is not tied to the visible sacraments, sanctifies man inwardly. Hence Ambrose says of Valentinian, who died while yet a catechumen, ‘I lost him whom I was to regenerate, but he did not lose the grace he prayed for’” (Summa Theologia III:68:2, cf. III:66:11–12).

As these passages indicate, Catholics have historically understood that what is absolutely necessary for salvation is a salvific link to the body of Christ, not full incorporation into it. To use the terms Catholic theology has classically used, one can be a member of the Church by desire (in voto) rather than in reality (in re).

This is necessary background for understanding the papal and conciliar statements radical traditionalists appeal to when trying to deny the reality of baptism of blood and desire. The popes and councils of the Middle Ages who emphasized extra ecclesiam nulla sallus had no intention of overturning what was standard teaching in their day regarding catechumens and baptism of desire.

The fact that certain radical traditionalists today do not understand this shows—ironically—how out of touch with Catholic tradition they are, since they do not understand the basic theological assumptions behind the magisterial texts they quote.

When confronted with such passages from Church fathers and doctors, radical traditionalists sometimes try a blocking move: “I don’t deny that those fathers and doctors said those things, but they were not infallible. The statements I quote from popes and councils are infallible, and so you should stick with what’s infallible and not pay attention to the non-infallible.”

There are a couple of reasons this argument is bad. First, when the Church defines something, it tends to define only a single point, which it does not intend it to be understood in a theological vacuum.

That’s why, for example, when Pius IX and Pius XII defined the Immaculate Conception and Assumption, they didn’t simply issue single-sentence documents containing only the definitions. The definitions they issued did consist of only single sentences, but they were contained within much larger documents that explained and prepared for the definitions so that everyone would understand what was being done.

Context is also the reason why ecumenical councils such as Trent would prepare for the canons (in which they infallibly defined certain points) by writing decrees that expounded at more length the points of theology that would be defined in the canons.

Similarly, whenever the Church issues a definition, it intends that definition to be understood in the context of the standard theology of the day. It intends its definitions to be taken in the sense that the approved doctors and fathers would understand them.

Indeed, magisterial definitions are made to shore up and defend the teachings of the approved doctors and fathers. If it were suggested to Boniface VIII or Eugene IV (the popes Feeneyites cite) that they were overturning the standard teaching on baptism of desire and blood, they would have been stunned and probably replied, “No, that’s not what I’m doing at all!”

Second, the Feeneyite’s blocking move is wrong because there are infallible statements regarding baptism of desire.

Canon four of Trent’s Canons on the Sacraments in General states, “If anyone shall say that the sacraments of the New Law are not necessary for salvation but are superfluous, and that although all are not necessary for every individual, without them or without the desire of them . . . men obtain from God the grace of justification, let him be anathema [i.e., ceremonially excommunicated].”

This is confirmed in chapter four of Trent’s Decree on Justification, which states that “This translation [i.e., justification], however, cannot, since promulgation of the Gospel, be effected except through the laver of regeneration [i.e., baptism] or its desire, as it is written: ‘Unless a man be born again of water and the Holy Ghost, he cannot enter into the kingdom of God’ (John 3:5).”

Trent teaches that, although not all the sacraments are necessary for salvation, the sacraments in general are necessary. Without them or the desire of them men cannot obtain the grace of justification, but with them or the desire of them men can be justified. The sacrament through which we initially receive justification is baptism. But since the canon teaches that we can be justified with the desire of the sacraments rather than the sacraments themselves, we can be justified with the desire for baptism rather than baptism itself.

To avoid this, some radical traditionalists have tried to drive a wedge between justification and salvation, arguing that while desire for baptism might justify one by remitting one’s sins, it would not communicate to one the state of grace and thus allow one to be saved if one died without baptism.

This is shown to be false by numerous passages in Trent. For example, in the same chapter that it states that desire for baptism justifies, Trent defines justification as “a translation . . . to the state of grace and of the adoption of the sons of God” (Decree on Justification 4).

Justification thus includes the state of grace. It is not a mere remission of sins. Since whoever is in a state of grace and adopted by God is in a state of salvation, desire for baptism saves. If one dies in the state of grace, one goes to heaven and receives eternal life. Justification, and thus the state of grace, can be effected through the desire for baptism (for scriptural examples of baptism of desire, see Acts 10:44–48; cf. Luke 23:42–43).

Trent also states: “Justification . . . is not merely remission of sins, but also the sanctification and renewal of the interior man through the voluntary reception of the grace and gifts, whereby an unrighteous man becomes a righteous man, and from being an enemy [of God] becomes a friend, that he may be ‘an heir according to the hope of life everlasting’ [Titus 3:7]” (Decree on Justification7).

Thus desire for baptism brings justification and justification makes one an heir of life everlasting. If one dies in a state of justification, one will inherit eternal life. Those who die with baptism of desire are saved. Period.