Homily for the Twenty-Third Sunday of Ordinary Time, Year B

“Ephphatha!”— that is, “Be opened!”

-Mark 7:34

Why do the Gospels on a few occasions convey the literal words of Our Lord in his native Aramaic in the middle of the Greek original? There is this Sunday’s healing command, and there is Our Lord’s command to the departed young girl, Talitha kum, and, most powerfully, his praying of Psalm 21 in crying out to his Father, Eli, Eli lama sabbacthani?

In the inspired scriptures, and especially in the Gospels, the most important of all the inspired scriptures, such a detail must have some spiritual significance. Let’s see what it might be.

If you saw Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ, do you recall what language the actors spoke? I did a little informal survey among some Catholics who had seen the film. They did not all recall directly. Some thought the film must have been in English, others said it was in Latin or Greek with subtitles in English, which is partly true, some said in Hebrew, which was close—but in Our Lord’s time Hebrew was a liturgical language reserved for worship and study, as Latin or Old Church Slavonic today. Only a very few said Aramaic, which is the dialect of Syriac that Our Lord spoke, as did most of the Jews after the exile in Babylon and their return. In fact this last is the truest answer. The dialogue was predominantly in Aramaic throughout the film: the language of Jesus, Mary, and Joseph.

What inspired Mel Gibson to use this original language time in his film? Let’s hear how he described the project:

“To bring a cast from all over the world to one place and have them all learn this one language gave them a sense of common ground, of what they share and of connections that transcend language,” he said. “It brought out a different level of performance. In a sense, it became good old-fashioned filmmaking because we were so committed to telling the story with pure imagery and expressiveness.

Opera lovers have a similar experience!

Consider the mystery of Pentecost, wherein the Holy Spirit inspired speech in a way that both strengthened and relativized the languages used: the same message in many tongues. This is the way the inspired authors of the Gospels and the Church in its liturgy also have worked, albeit in a less miraculous way. We never completely discard the ancient speech for the new, and when the new speech became ancient (as when the Roman Church went from using Greek to Latin in its worship) some echoes were still preserved it in the rites and prayers.

Thus we have Amen, Alleluia, Kyrie eleison, Hagios o Theos, Marana-tha. And when that in turn becomes old, the Church continues the custom of conservation.

I once heard a very wise old bishop years ago, Archbishop Dwyer of Portland in Oregon, opine that the reason the Charismatics (who were a new thing in the far-off seventies) liked to “sing in the spirit” was because this practice restored to them a sense of mystery in their worship that they had lost when Latin chant was replaced with American English and guitars. You can be sure that those “singing in the spirit” did not understand their utterances any more than they had understood the Latin, but in both cases they knew exactly what they were doing in offering worship to God. In worship, language both reveals and conceals; it defines and it goes beyond definitions.

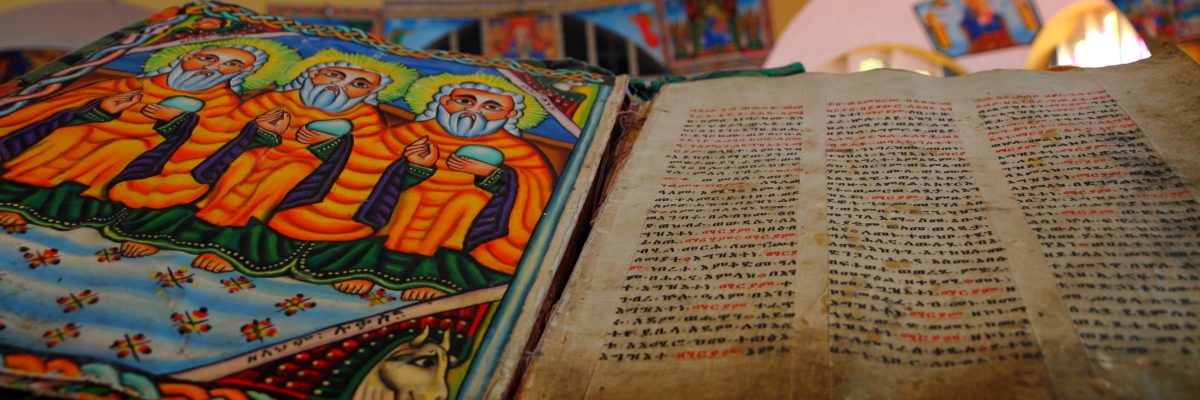

It is simply a fact that there is not a single rite of the Catholic Church, in the East or in the West, that did not develop an ancient form of language for use in worship. Even as we began to use the vernacular almost universally, the church still preserved the use of its liturgical language. Latin, Patristic Greek, Old Slavonic, Classical Armenian, Coptic, Ge’ez, various kinds of Syriac, and so on. And now, arguably, with the Anglican Ordinariate, the Church is preserving an older “liturgical” form even of English that is not the form of everyday speech. Not only that: the Church has encouraged the use and maintenance of these tongues as the bearers of its tradition.

Antiquity is a sign of authority, of a phenomenon that goes back to the beginning, and so is durable and credible. Go back to your beginning as a Christian at Holy Baptism and you will find that in the rite of baptism the priest spoke the very command, and in the very same language, that we heard Our Lord speak in today’s Gospel lesson: Ephphata! “Be opened!”

So may Jesus open our ears to hear and our mouths to praise in the beautiful languages he and his holy Church have used and still use to reveal his truth, and show his power that goes beyond all human telling.