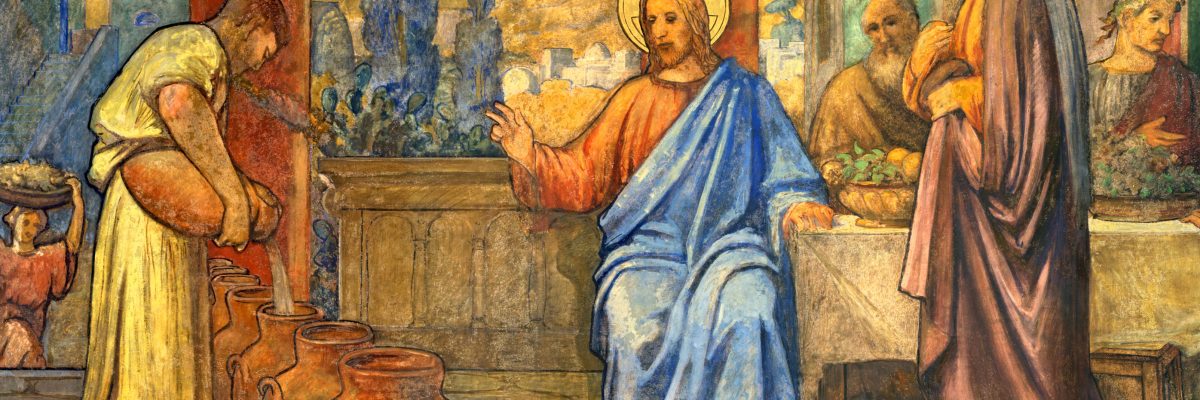

Jesus frequently worked his miracles through others. Take the wedding at Cana, for example. As far as we can tell, Jesus never touches the water or the wine or the jugs. Instead, Mary asks Jesus for the miracle, and then tells the servants, “Do whatever he tells you” (John 2:5). Jesus then instructs them, and they do as they’re told.

It’s still Jesus working the miracle, of course. As John says, “This, the first of his signs, Jesus did at Cana in Galilee, and manifested his glory; and his disciples believed in him” (John 2:11). We might describe the servants as “ministers of the miracle.” They perform the miracle but not of their own power. Or Jesus performs the miracle through them.

Jesus works the same way in the sacraments. After he tells Nicodemus that “unless one is born of water and the Spirit, he cannot enter the kingdom of God” (John 3:5), Jesus and the disciples go to Judea; there “he remained with them and baptized” (John 3:22). Even though “Jesus himself did not baptize, but only his disciples,” nevertheless, the Evangelist can say that “Jesus was making and baptizing more disciples than John” (John 4:1-2).

That’s also why the people John the Baptist baptized were rebaptized (since his baptism was symbolic and didn’t impart the Holy Spirit: see Acts 19:1-7), but the people Judas baptized weren’t. As St. Augustine said, “those whom John baptized, John baptized; those whom Judas baptized, Christ baptized.”

The disciples are ministers of the sacramental miracle. That’s the whole basis of the Catholic understanding of the sacraments. They work, not because of the holiness—at best imperfect, at worst nonexistent—of the sacramental minister but because of the holiness of Christ himself, the one at work through the minister.

This is true of all of the sacraments, including the Eucharist. In Mark 8:19-21, Jesus reminds his disciples that there were two different miracles of the multiplication of the loaves, and he spurs them on to understand the deeper meaning of the miracle. One part of that deeper meaning may be discerned from looking at the Gospel language very carefully. Specifically, the Evangelists typically describe Jesus as doing the same five things, in the same order: (1) taking the bread; (2) giving thanks and blessing it; (3) breaking the bread; (4) giving it to the disciples; and (5) sending the disciples to do the same to the crowds. We see this pattern repeatedly in the Gospels:

- “Taking the five loaves and the two fish he looked up to heaven, and blessed, and broke and gave the loaves to the disciples, and the disciples gave them to the crowds” (Matt. 14:19).

- “He took the seven loaves and the fish, and having given thanks he broke them and gave them to the disciples, and the disciples gave them to the crowds” (Matt. 15:36).

- “Taking the five loaves and the two fish he looked up to heaven, and blessed, and broke the loaves, and gave them to the disciples to set before the people; and he divided the two fish among them all” (Mark 6:41).

- “He took the seven loaves, and having given thanks he broke them and gave them to his disciples to set before the people; and they set them before the crowd” (Mark 8:6).

- “And taking the five loaves and the two fish he looked up to heaven, and blessed and broke them, and gave them to the disciples to set before the crowd” (Luke 9:16).

Are the Evangelists just making sure that we understand how eating works? Or might there be something more?

The answer, of course, is “something more.” These passages don’t read like ordinary “eating” language. Contrast with Luke 24:42-43: “They gave him a piece of broiled fish, and he took it and ate before them.” Instead, the language is that of the Eucharist. John tells us that the Feeding of the Five Thousand takes place around Passover, a year before the Last Supper (John 6:4), and these miraculous loaves prefigure the Eucharist. The Greek word being translated in these passages as “gave thanks” is eucharisteō, from the same root as Eucharist. And remember that “the breaking of the bread” is one of the ways that Christians first referred to the eucharistic liturgy (Acts 2:42). The connection between these two sets of passages is clear once you pay close attention to the words used:

- “And he took bread, and when he had given thanks he broke it and gave it to them, saying, ‘This is my body which is given for you. Do this in remembrance of me’” (Luke 22:19).

- “For I received from the Lord what I also delivered to you, that the Lord Jesus on the night when he was betrayed took bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it, and said, ‘This is my body which is for you. Do this in remembrance of me’” (1 Cor. 11:23-24).

Notice that same precise sequence of actions: taking the bread, giving thanks (“eucharisting” it), breaking it, and giving it to the disciples. But what about the last step? In the multiplication miracles, Jesus gave the loaves “to the disciples, and the disciples gave them to the crowds” (Matt. 15:36). Where do we see that in the institution of the Eucharist? In the instructions to “do this.” Jesus gave “the one bread” (1 Cor. 10:17) to the disciples and then instructed them to do the same, thereby sharing this miracle with the crowds.

His instruction “Do this in remembrance of me” is a permanent command to the apostles and their successors. But it’s not the bishop or priest celebrating the Mass who performs the miracle. It’s Christ himself, which is why the celebrant says “This is my body” rather than “This is his body.” The priest is there as the minister of the miracle. His job, like that of the servants at the wedding of Cana, is to do whatever Christ tells him.