Determining a bad idea’s antecedents usually is messy and often is impossible. Just when did a particular bad idea begin? Seldom is there an analogue to Athena coming fully formed from the forehead of Zeus.

Usually one bad idea derives from an earlier bad idea, which in turn derives from still earlier bad ideas. In order not to get lost in a long series that disappears into the mists of pre-history, you need to choose a point at which you can say, “For purposes of discussion, I count this as the origin of this bad idea.”

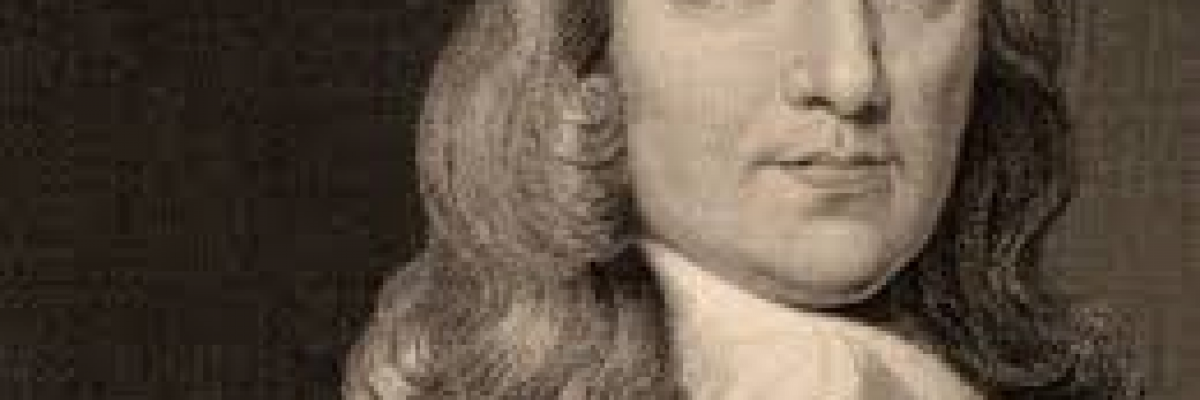

I’m going to blame last week’s same-sex marriage decision on the poet John Milton. Let me explain.

I don’t at all mean that Milton or any of his contemporaries or anyone for centuries following endorsed or even thought of same-sex marriage. I don’t know whether Milton ever wrote anything about homosexuality, but, if he had, no doubt he would have concurred with the sense that, as today’s Catechism of the Catholic Church says, homosexuality is a “serious disorder.” The people of Milton’s time, the seventeenth century, wouldn’t have left it at that, of course. They would have seen the state of being homosexual as being not just a disorder but a choice deserving of the strictest punishment.

No, I’m giving Milton first dibs on the blame for same-sex marriage because he was the first substantial writer in English to argue for divorce. Yes, Henry VIII preceded Milton by a century and so can be blamed for putting divorce into practice in a public way, but Henry’s theory of divorce was limited to his desire for a divorce for himself. Had Catherine of Aragon been able to provide the king with a son, probably Henry wouldn’t have said a word about divorce. His was a position of expediency. Milton’s position was one of principle, even if a flawed principle based on a flawed interpretation of Scripture.

At the beginning of the English civil war, in 1643, Milton wrote The Doctrine & Discipline of Divorce. He was the first major writer (though not the very first writer) to argue that, in certain circumstances, divorce is a good thing and fully comports with Christ’s teaching.

This was not a widely popular view among Christians at large, yet divorce ended up being permitted, for cases of infidelity or abandonment, by the Westminster Confession of Faith, which was drawn up in 1646. Milton gets some of the credit (or blame) for that. The Westminster Confession represented the Reformed point of view, particularly of Scottish Presbyterians, but its terms later were adopted, with modifications, by other religious bodies.

What Milton accomplished was to undermine the notion that marriage is life-long, that it is a permanent commitment, irrevocable once entered into. Of course there was no sea change in people’s outlook. Most still thought of marriage as permanent and would continue to think that way for another three centuries, but Milton legitimized the notion of impermanence, and over time that notion held wider and wider sway, eventually culminating in the no-fault divorce movement of five decades ago.

Today almost everyone understands marriage to be a matter of convenience: easy to enter and easy to leave, with no expectation of permanence, even if the vows still say “until death do us part.”

Marriage has three chief attributes. Aside from permanence they are an ordering toward the begetting and rearing of children and an ordering toward the mutual help and unity of the spouses. That mutual help takes several forms, but the most important one was mentioned to my bride and me by the priest who officiated at our wedding. He said the most important goal of marriage is to help one’s spouse achieve heaven. After all, salvation is the goal of all of the sacraments.

Once divorce became accepted, even if uncommon, it was not long before another chief purpose of marriage was undermined: the begetting and rearing of children. If one understood marriage to be impermanent, it made sense, in a way, to think it a good thing not to burden oneself with the nearly-permanent task of raising offspring. There were mechanical and, eventually, chemical fixes for that.

As is widely known in orthodox circles, all Christian churches forbade contraception, in all circumstances, until the Anglican Church’s 1930 Lambeth Conference, which permitted the practice for married couples, though only in exceptional circumstances.

Like cracks in a dam, exceptional circumstances always expand over time. They never contract. Within less than a generation most Christians—certainly the majority of Protestants but even by then a substantial minority of Catholics—came to accept the legitimacy of contraception, thus severing marriage and procreation. This was the situation by the end of the 1950s. The reaction to Humanae Vitae, issued by Pope Paul VI in 1968, was almost an afterthought.

It’s a pity that the encyclical hadn’t been issued in 1928, when it already was clear that an effort would be made, by Anglicans at their upcoming conference, to legitimize contraception. An early and forceful opposition, even to a proposal within a non-Catholic religious body, might have had salutary effects.

However that might have been, the logic that Milton gave an impetus to kept going its merry way. Pope Paul warned that abortion would follow contraception. People scoffed, and the elderly, unmarried Pope was proved right (a habit that popes have tended to have throughout the years).

Over the last half century marriage has shed most of its traditional attributes. It no longer is permanent, need not have anything to do with children, and certainly is not thought of as a means to effect another’s salvation. It has become protean: it can be whatever one desires it to be.

If the institution no longer binds a man and a woman for life, why should it bind anyone? Why should it even be bound by its own traditional form? Marriage once was about the other: God, one’s spouse, one’s children. Now it is about the self, in whatever combinations the self may wish to seek fulfillment.

At the beginning of Paradise Lost Milton explained his purpose: “to justify the ways of God to men.” His epic hardly is read any longer, but the spirit of The Doctrine & Discipline of Divorce has become entrenched. His little-known work has eclipsed his best-known work in terms of influence on society. When it comes to marriage, most people think the ways of God have nothing to do with it, except perhaps ceremonially on the day of the wedding.

Thanks, Mr. Milton.