In 2014, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc. that some businesses were exempt from the Affordable Care Act contraception mandate if they had a religious objection to it. After the decision was released, Ronald Lindsay, an advocate for atheism and author of the book The Necessity of Secularism, penned an online essay titled “The Uncomfortable Question: Should we Have Six Catholic Justices on the Supreme Court?” Lindsay mentioned past anti-Catholic prejudice and his own risk of sounding bigoted, but he still argued that the Court’s ruling could be explained only as the result of Catholics following the rule of the pope rather than the rule of law.

Imagine the outcry if Lindsay had complained about a group of female judges he claimed were biased against men. What if Lindsay had complained that there were too many Jewish judges on a certain appeal circuit? In those cases, there would be widespread condemnation, but because Lindsay attacked Catholics, he was given a free pass.

This double standard is nothing new. When we trace the history of Catholicism in the United States back through the centuries, we see that not only is anti-Catholicism the last acceptable prejudice, but it was also one of the first.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, British colonists traveled to the New World in search of religious freedom. They found it—but only for their respective churches. Most of the colonies established some form of Anglicanism or congregationalism as their official religion, whereas other Protestants, not to mention Jews and Catholics, were subject to persecution if they did not attend these worship services.

Some colonies would not even tolerate the existence of these religious groups, which is evident in Massachusetts’s “Act against Jesuits and Popish Priests,” passed in 1700, which gave Catholics several months’ notice that they had to leave the province. Even the colony of Rhode Island, whose tolerance for members of religious minorities earned it the nickname “Rogues’ Island,” forbade Catholics from serving in public office.

Why were Catholics treated so poorly? Many of these early eighteenth-century restrictions were a response to the so-called “Jacobite uprising” in England in 1745 that attempted to install the Catholic prince of Wales, James Stuart, to the English, Scottish, and Irish thrones. The plan failed, leaving the prince’s father, James II, as the last Catholic monarch to ever reign over the British Isles.

The other prominent location of Catholics in America was the colony of Maryland, which its founder George Calvert actually called terra mariae, or Mary Land. Even though this colony would become home to the first American diocese, it still had a majority-Protestant population. After Calvert’s death, his son Cecil gave the following instructions to the governor of Maryland in hopes that a Protestant majority would not erode the religious freedom Catholics enjoyed: “Instruct all the Roman Catholics to be silent upon all occasions of discourse concerning matters of Religion; and that the said Governor & Commissioners treat the Protestants with as much mildness and favor as Justice will permit.”

By the mid-nineteenth century, the Industrial Revolution drew hundreds of thousands of Americans out of the farmlands and into urban areas. In the 1840s, the Catholic population in these areas exploded after the Irish potato famine brought millions of Irish immigrants to cities like Boston, New York, and Baltimore. These Catholics formed labor unions to protect themselves from violence and discrimination, the latter of which could be seen in “Irish need not apply” signs that littered storefronts across the United States, some as late as 1909.

Despite this hostility, Catholic immigration to the United States accelerated, and anti-immigrant activists blamed increased public welfare spending and rising crime rates on the “hordes” of Catholics flooding the country. Some critics also saw the influx of Catholics as a threat to democracy itself because of Pope Leo XIII’s condemnation of “Americanism,” or the heretical view that the Church should have no influence on public policy but should instead adapt to a changing culture.

Unfortunately, many people interpreted the pope’s exhortations for the Church to shape society as a mandate to conquer it and instill a theocracy. Ellen G. White even claimed that Catholics would force all citizens, including her fellow Seventh-Day Adventists, who celebrate the Sabbath on Saturday, to worship on Sunday. (Some Adventists still promote this conspiracy theory in a book called National Sunday Law.)

The combination of fear and resentment toward Irish, Italian, and German Catholics also fueled the rise of a semi-secret political society called the Know-Nothing Party. The name came from the group’s members, who would say they knew nothing about whatever the organization was planning. It’s no surprise they stayed tight-lipped, given that the Know-Nothings used violence and intimidation to keep Catholics and other immigrants from being elected to public office.

On August 6, 1855, what is now called Bloody Monday, armed Know-Nothing mobs controlled the city of Louisville, Kentucky, and made a show of force to prevent Catholics from “rigging” the day’s election. What came next were a series of beatings, lootings, acts of arson, and murders that resulted in the deaths of at least twenty-two people and the near destruction of the city’s cathedral.

Unfortunately, the Know-Nothings’ tactics won dozens of state and local elections in the 1850s, when they ran as the American Party. After one of their candidates, Levi Boone, was elected mayor of Chicago, he banned immigrants from the city’s government and police force. The Know-Nothings also sought to ban Catholics from holding public office.

Article VI of the U.S. Constitution specifies that “no religious test shall ever be required as a qualification to any office or public trust under the United States,” but this applies only to positions in the federal government. States and local municipalities could exclude atheists, Jews, Catholics, and other religious groups from public office until the Supreme Court’s 1961 Torcaso v. Watkins case ruled that religious tests represented an establishment of religion and were therefore unconstitutional.

As quickly as the Know Nothings appeared, by 1860, the party was torn apart by the issue of slavery. Anti-slavery Know-Nothings became Republicans, whereas the pro-slavery members joined the Constitutional Union party, which faded out of existence after losing the 1860 presidential election. But the demise of the Know-Nothings did not end the spread of their anti-Catholic rhetoric.

The most infamous group that assumed the anti-Catholic mantle was the Ku Klux Klan. Decades before their assault on racial integration, the Klan fought to protect white, Protestant America from “papists” who it claimed were immigrating to conquer America by numbers and even by force. Many Klan members believed that every Catholic parish kept a stockpile of weapons to use in a future war against Protestants.

Even though Klansmen had no qualms about using violence and other intimidation tactics, they considered their most potent weapon against the Church to be mandatory public school attendance. In 1922, the Klan teamed up with the Freemasons to pass the Oregon Compulsory Education Act. They hoped public school would tech Catholic children “civic lessons” and wean them off their troublesome immigrant heritage, including their attachment to their Catholic faith. The act would also have the practical effect of closing down every parochial school in the state.

Thankfully, after vocal opposition from parents and campaigning by the then-forty-year-old Knights of Columbus, the case was brought before the Supreme Court. In 1925, the Court ruled in Pierce v. Society of Sisters that the Compulsory Education Act was unconstitutional and that parents have a right to determine their children’s education.

Even though the Supreme Court sided with the Church on school choice, Protestant America still viewed Catholics with deep suspicion. In 1928, Al Smith became the first Catholic nominated for the presidency, but he lost the election, at least in part, because of his Catholic faith. In one case, Smith was accused of imposing his Catholic morality on the public because of his opposition to alcohol prohibition, a stance that drew heavy backlash from teetotaling Protestant moralists.

It would be more than thirty years before another Catholic ran for president, and Protestant opposition remained fierce. The famous evangelist Billy Graham convened a group of his fellow Protestants in Montreux, Switzerland, in order to devise a plan to halt the momentum of John F. Kennedy’s campaign.

In the face of this criticism, Kennedy realized the importance of keeping the “religion question” from sidelining his message to voters, so on September 12, 1960, he gave a historic speech to the Greater Houston Ministerial Association that provided the framework for future Catholics to assuage the fears of non-Catholic voters. He said,

I am not the Catholic candidate for president. I am the Democratic Party’s candidate for president who happens also to be a Catholic. I do not speak for my church on public matters, and the Church does not speak for me. Whatever issue may come before me as president—on birth control, divorce, censorship, gambling, or any other subject—I will make my decision in accordance with these views, in accordance with what my conscience tells me to be the national interest, and without regard to outside religious pressures or dictates. And no power or threat of punishment could cause me to decide otherwise.

So where are we today? According to the Gallup polling agency, in 1958, only two thirds of Americans were willing to vote for a Catholic presidential candidate. Today, 94 percent would do so, but that willingness often assumes that the candidate will not impose his faith on the American people. This includes not just the imposition of sectarian morality (like legislating mandatory Mass attendance), but the imposition of Catholic principles that all people should be able to recognize from reason alone, such as the right to life for unborn children.

Do Catholics still face prejudice in American politics today? Probably not, so long as their Catholic identity is a line in their biography or a photo opportunity of something innocuous like helping at a Catholic food bank. But when Catholic politicians try to defend the unborn’s right to life or the natural definition of marriage, you can bet their faith will become a target for criticism.

But that cannot stop them or us from acting in accordance with our faith in the public square. To do so would render in vain the many sacrifices Catholics have made that ensure that you or I can run for office or even have a voice in the polling place and public marketplace of ideas.

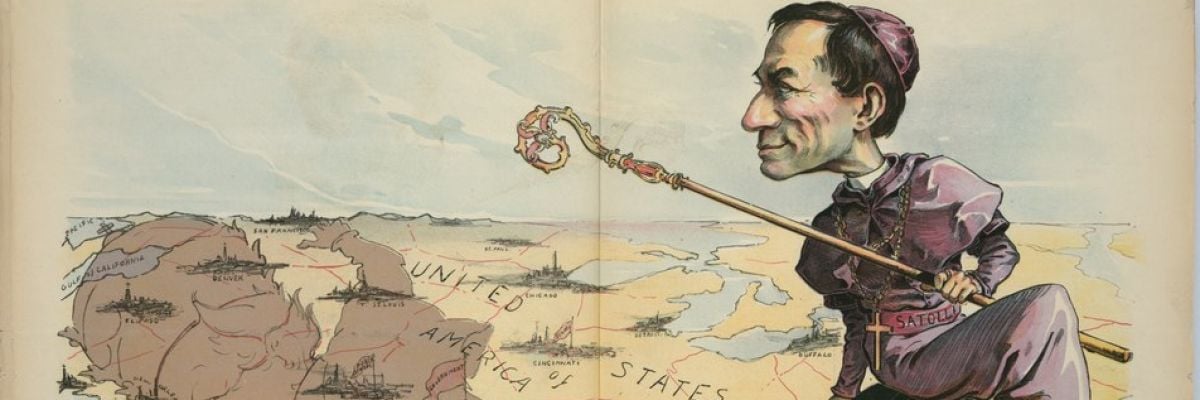

Art: A 1894 print by Udo Kepler shows Cardinal “Satolli” holding a crosier, sitting atop an enormous dome labeled “American Headquarters” and casting a large shadow in the shape of Pope Leo XIII across the landscape of the United States. Several cities, some with buildings labeled “Public Schools,” are encompassed by the shadow of the pope, including New York City, the U.S. Capitol building, “Memphis, New Orleans, El Paso, Denver, [and] San Francisco.”