The miracles of Jesus are “living parables” illustrating and animating his teachings. This is a stark contrast from the way Jesus is sometimes depicted in the false gospels. For instance, in the so-called Infancy Gospel of Thomas, the young Jesus is presented as striking another child dead in a fit of irritation after the running child bumped Jesus’ shoulder. It’s raw power, with no meaning beyond “I can do this.”

The biblical miracles, on the other hand, are of a completely different character. It’s for this reason that we see the Jesus of the Bible exercising his divine power not by killing people but by healing them and even raising them from the dead. Commenting on the three instances of the latter, St. Augustine notes, “Surely the Lord’s deeds are not merely deeds but signs. And if they are signs, besides their wonderful character, they have some real significance.” In these cases, he suggests, the deeper meaning is that “everyone [who] believes rises again” (Tractate XLIX on John [John 11:1-54]).

The scriptural way of describing this dimension of miracles is calling them “signs” or “signs and wonders” (cf. Deut. 6:22, John 2:11, Acts 6:8, et al.). With any of the biblical miracles, we should ask, “What was the meaning of this miracle?”

For instance, although Jesus doesn’t kill an innocent boy in the New Testament, he does cause a fig tree to wither and die (Matt. 21:18-22). The British philosopher Bertrand Russell said that the “curious story” had “always rather puzzled me,” and he cited this incident as a “moral problem” that showed Christ’s inferiority to teachers such as the Buddha and Socrates (Why I Am Not a Christian, 19).

But Jesus isn’t behaving in an insensitive or ill-tempered way. Recall that John the Baptist had prepared the way for Christ by calling his listeners to “bear fruit that befits repentance,” since “every tree therefore that does not bear good fruit is cut down and thrown into the fire” (Matt. 7:19). Jesus continued with this imagery, comparing the spiritual fruitlessness of Israel to a barren fig tree (Luke 13:6-9), drawing upon the prophetic language of Isaiah 5.

When Christ causes the fruitless fig tree to wither, he’s not having an emotional outburst nor “punishing” the tree as if it were capable of knowing right from wrong. Instead, it’s as if Jesus is enacting the parable of the fig tree.

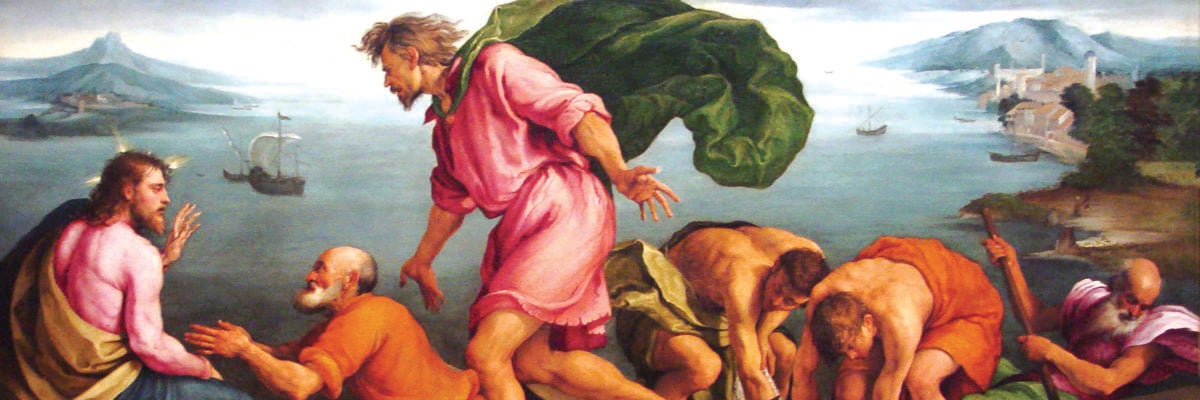

What, then, are the three miracles involving a miraculous catch of fish, and why is St. Peter closely involved in all three? The answer seems to be something about the Church, and the particular role of Peter as the head of the Church. One curious feature about the three miracles is that, even though Jesus is the supernatural power behind the scenes, in each case it is Peter who is on the front lines, actually bringing in the fish.

Duc in altum

In the first miracle, Jesus tells Peter to “put out into the deep and let down your nets for a catch” (Luke 5:4-5). He does so, and there’s a miraculous catch of fish. Jesus then says to him: “Do not be afraid; henceforth you will be catching men” (Luke 5:10). The message seems clear enough. Jesus is using fishing, which Peter knows well, as a kind of metaphor for faithful evangelization. After all, as the nineteenth-century Baptist preacher Charles Spurgeon observed, “A fisher is a person who is very dependent, and needs to be trustful,” and every fishing expedition is a sort of act of faith, venturing into the unknown waters (The Soul Winner, 232).

But there’s another dimension: in his Gospel account, St. Luke takes special note of the nets, mentioning them four times. If the fishing represents evangelization, and the fish represent those to whom the gospel will be preached, what do the nets represent? The Church. After all, it’s here that the “fish” are gathered together.

And what about Peter’s role? After all, Jesus speaks to Peter specifically about how he will be the one doing the fishing and the casting out of the nets for a catch. By itself, that may not seem like an important detail. But this is in front of a large crowd (Luke 5:1), and Peter is working alongside Andrew, James, and John (Luke 5:10, Mark 1:16). Standing before the crowd, in the company of at least four men who will make up his Twelve, Jesus singles out Peter with a message about how he will be in charge of evangelizing and gathering the flock together.

The second miraculous catch

The other famous miraculous catch happens at the Sea of Tiberius at the end of St. John’s Gospel. This time, Simon Peter says, “I am going fishing,” and six other disciples follow him, saying, “We will go with you” (John 21:2-3). Already, John is illustrating the Church for us: Peter as the fisherman with the others fishing with him.

But they are unable to catch any fish, and so they toil all night with no result. At daybreak, the resurrected Jesus appears to them, tells them to “cast the net on the right side of the boat,” and they obey, resulting in such a large catch that “they were not able to haul it in for the quantity of fish” (John 21:6).

St. Augustine saw in this a reference to the eschatological mission of the Church: “The Lord indicated by an outward action the kind of character the Church would have in the end of the world” (Tractate 122 on John [20:30-21:11]). In other words, John shows the disciples not only as fishers of men but as bringing us safely home to the other side, hauling the net of the Church to the eternal shores of heaven and to the glorified Christ. It’s why John mentions that there are seven disciples, since seven is the biblical number of completion and of heavenly rest (cf. Heb. 4:4).

Perhaps that interpretation seems far-fetched. Why would we read into this any more than a story about fish being brought ashore? Besides the instance we’ve already seen in which Jesus used the miraculous catch as a way of making a point about the Church and evangelization, we also have his explicit teaching on the matter:

Again, the kingdom of heaven is like a net which was thrown into the sea and gathered fish of every kind; when it was full, men drew it ashore and sat down and sorted the good into vessels but threw away the bad. So it will be at the close of the age. The angels will come out and separate the evil from the righteous and throw them into the furnace of fire; there men will weep and gnash their teeth (Matt. 13:47-50).

How does he depict the earthly Church? As a net, containing both good and bad fish. And what’s represented by the net being drawn ashore? The “close of the age,” the end of the world in which the just will be separated from the wicked. Jesus is using a consistent set of images, in his word and in his deeds. Augustine’s reading of John 21 simply recognizes this fact.

But notice that the leaders of the Church can’t do it on their own. By themselves, they catch nothing, and even when they do catch the miraculous haul, they cannot bring it ashore. Thankfully, this isn’t the end of the story. Jesus orders them to “bring some of the fish that you have just caught,” and so “Simon Peter went aboard and hauled the net ashore, full of large fish, a hundred and fifty-three of them; and although there were so many, the net was not torn” (John 21:10-11).

Even though Jesus’ instructions are to all of the disciples, John tells us that it is Simon Peter who brings the nets in. Remember, these are the same nets that all of them together were unable to bring in, moments earlier. Now, at the command of Jesus, Peter not only brings the catch home to Christ, he does so without tearing the nets.

And when John says that the nets are not “torn,” he uses the word schisma, the root of the word schism. Peter has a special role in bringing the Church home to Christ, precisely by keeping us united in one fold, since we would otherwise fall into schism and not make it home safely.

This special role of Peter is reiterated throughout the final chapter of John’s Gospel in ways small and large. The disciples’ breakfast with Jesus is cooked over a “charcoal fire” (John 21:9). Why does John mention such a seemingly trivial detail? Because it was over a charcoal fire that Peter had denied Jesus (John 18:18).

After breakfast, Jesus famously asks Peter three times, “Do you love me?” (John 21:15-17). But in fact he goes further, asking, “Simon, son of John, do you love me more than these?” (John 21:15). Here there is less subtlety: Peter’s threefold proclamation of faith is a sort of healing for his earlier threefold denial. And after each time, Jesus says to Peter, “Feed my lambs,” “Tend my sheep,” and “Feed my sheep.”

The Good Shepherd is calling the fisherman as his shepherd. Once more, amid the other disciples, Jesus has singled Peter out as the leader of his Church.

The overlooked catch

These two miraculous catches of fish are the well-known ones. But between these two events, there’s a third miraculous catch, a much smaller one that we often overlook. Tax collectors approach Peter in Capernaum, asking whether or not Jesus pays the Temple tax (Matt. 17:24). This leads to an exchange between Jesus and Peter:

And when he [Peter] came home, Jesus spoke to him first, saying, “What do you think, Simon? From whom do kings of the earth take toll or tribute? From their sons or from others?” And when he said, “From others,” Jesus said to him, “Then the sons are free. However, not to give offense to them, go to the sea and cast a hook, and take the first fish that comes up, and when you open its mouth you will find a shekel; take that and give it to them for me and for yourself” (Matt. 17:25b-27).

Perhaps it’s understandable why we hear so little about this miracle. It’s a seemingly small affair, and it involves Jewish Law and tax code. But remember, Jesus’ miracles are all signs, and we should be looking for what he’s teaching us by each one. In fact, Jesus has just made one of the most shocking statements about Peter, and we’ve missed it.

A little background is necessary. The tax in question is the “half-shekel tax.” The Mosaic Law held that “each who is numbered in the census” shall give “half a shekel as an offering to the Lord” (Exod. 30:13). The wording there is important, because it suggests a sort of clerical tax exemption.

The Aaronic priests and Levites who assisted the priests were from the tribe of Levi, which was not counted amongst the census (Num. 1:49). And this exemption made sense: after all, the tax was for the maintenance of the sanctuary, and the priests and Levites were more directly involved in the sanctuary’s upkeep.

By the time of Jesus, the Levites were no longer considered exempt, but the priests still generally were (Sebastian Selvén, “The Privilege of Taxation: Jewish Identity and the Half-Shekel Temple Tax in the Talmud Yerushalmi,” Svensk Exegetisk Årsbok, vol. 81, p. 70). So, when Jesus talks about the “sons” being exempt, he doesn’t mean (as we might assume at first) the native sons of Israel.

On the contrary, this tax applied only to Israel, and it was foreigners who were exempted. Instead, Jesus is saying that he and Peter are sons of the Temple—that is, priests. You can see why claiming this clerical tax exemption would “give offense to them.”

And so, Jesus sends Peter once more to go fishing. This time, he doesn’t need a net, because his instructions are to take only “the first fish that comes up,” in order to pay the Temple tax “for me and for yourself.”

Peter singled out

Once more, Jesus has singled out Peter. Why not a net of fish, with enough coins for everyone, or at least for the other disciples? The Reformer John Calvin was flummoxed by this. He suggested that it was perhaps simply a coincidence, “because Christ lived with him; for if all had occupied the same habitation, the demand would have been made on all alike” (Bible Commentaries on the Harmony of the Gospels, vol. 2, p. 300).

But Jesus isn’t performing miracles randomly for whomever happens to be around. Three times, he’s performed miracles involving catches of fish, and in each case, he’s performed the miracle through Peter. Moreover, the text suggests that the other disciples were around, since a little earlier they came to Jesus privately, they gathered in Galilee, and then they came to Capernaum, the site of this miracle (Matt. 17:19, 22, 24). Jesus is trying to teach us something about the special role of Peter.

This is clearer in the Greek: when Jesus talks about not wanting to give offense, the word in question is skandalisomen. That’s the verb form of skandalon (meaning a “stumbling stone,” from which we get the English word scandal), and it’s the term that Jesus used for Peter (negatively) in Matthew 16:23 and that Peter used for Jesus (positively) in 1 Peter 2:8. No other individual in the New Testament ever has the term applied to him, either positively or negatively.

So, the root word itself is already laden with meaning. But here it’s a verb, in the first-person plural. Why does that matter? Try to find another time in which Jesus refers to another person and himself as “we.”

You might be thinking, “What about the Our Father? Doesn’t Jesus use the first-person plural there?” No. He says that this is for “when you pray” (Matt. 6:5). His relationship with the Father is so unique that he even refers to him as “my Father and your Father” and “my God and your God” (John 20:17). Part of Jesus’ revelation is that he’s the Son of God in a different way than we’re children of God. So he stresses our dissimilarity from him.

When he does use “we” language (e.g., John 14:23), he usually does so to refer to the Persons of the Trinity. On the rare instances in which we find Jesus using “we” language, the listener is never within the net of that “we.” There is one exception, and it’s right here. When Jesus talks about how they don’t want to give offense, he’s catching up Peter in the net of his “we.”

That doesn’t mean that Peter somehow becomes a fourth Person of the Holy Trinity. It means instead that Jesus is giving him a special mission to serve as his vicar and to speak and act on his behalf. And what does this look like? In this case, it looks like Jesus sending Peter on a miraculous mission to get exactly enough money to pay the tax for just the two of them and then Peter paying the tax on Jesus’ behalf.

These three miraculous catches belong together, and they belong alongside Jesus’ teaching on the God’s earthly kingdom as a net of fish. The resulting picture is clear. Jesus wants his Church gathered together like a net overflowing with fish. He doesn’t want a thousand small nets, competing with one another, and he doesn’t want schisms tearing the nets apart.

And so what does he do? He entrusts Peter with a special mission of evangelization—but also a special call to serve as his vicar, to ensure the unity of the Church. And this Petrine office is destined to continue until the day in which Peter brings the net of the Church safely to the shores of heaven.

Sidebar: Miracles and Evangelization

The miraculous catches remind us of the need to trust in God, a lesson that fishing itself teaches. C.S. Lewis describes miracles as “a retelling in small letters of the very same story which is written across the whole world in letters too large for some of us to see” (“Miracles” in The Grand Miracle, 5).

The supernatural events in the Bible tend to build upon, and in some way resemble, natural events. And as the nineteenth-century Baptist preacher Charles Spurgeon observed, “A fisher is a person who is very dependent and needs to be trustful”; since he cannot see the fish, every act of fishing is “an act of faith” (The Soul Winner, 232; emphasis in the original). The Reformed theologian Tim Challies likewise suggests five ways that fishing resembles evangelization: both require going forth, expertise, diligence, dependence on providence, and confidence (“How Evangelism Is Kind of Like Fishing,” online at chaillies.com).

At the same time, we shouldn’t miss the obvious: these three particular miracles are also personalized for Simon, who was a fisherman by trade. They’re also closely connected with Jesus’ description of the kingdom of God on Earth (Matt. 13:47). In other words, these are the sort of miracles we shouldn’t be surprised to find if Jesus intended to entrust the Church to the care of the “fisher pope,” Peter.