There’s a meme that’s made several rounds on Catholic social media that features a potato and the caption “If this can become vodka, you can become a saint.” Funny enough, and the sentiment is well-meaning—but mere vegetables don’t tend to inspire me to sanctity (with some exceptions). My greatest motivation still comes from the saints—especially the modern ones. This is why I and many others are excited for Pope Leo’s imminent canonizations of Bls. Pier Giorgio Frassati and Carlo Acutis.

One of the main reasons we venerate saints is because they demonstrate how to imitate Christ in a particular time and place, outside the setting in which he lived. The modern First World sometimes seems to put up an impenetrable barrier between the cultures of Christ’s time and our own. But when an incredibly holy person rises up in our time, he gives a glimpse of how Christ would have lived in our time. Then the stark, radical otherness of Christ hits me in the face anew.

Relative to me, this has to apply to the saints, too. “Our time” is my time but not the time of an eighteenth- or a fifteenth- or a twelfth-century Christian. These saints, like Jesus, are separated from me by a massive gulf in time and place, and so the radicalness of their lives does not impact me strongly. In just the last century and a half, human civilization has changed so rapidly as to be nearly indistinguishable from the vast part of Church history.

Carlo Acutis and Pier Giorgio Frassati break through that barrier thanks to what I’m calling the “he’s just like me” factor. (“Relatability” is such a trite term nowadays.) In them we see young men living in a rapidly changing modern world while not being of it. A happy consequence is that for every story of their seemingly untouchable devotion to God, there is an anecdote or quirk that jolts them back into my field of view.

Thus we hear stories of Pier Giorgio giving all his bus fare to the poor and running home for supper every night interlaced with those relating the ever-escalating prank wars he waged with his friends. We learn that he joined so many organizations for Catholic youth that he could barely attend all the meetings, and also that he loved nearly every form of outdoor recreation. One minute I’m reading about his intense, powerful, reverent state of prayer after receiving daily Communion; next, I’m learning that he flunked Latin class twice.

He was boisterous, as youth are apt to be, yet he channeled that energy into stirring up others to prayer and sacrifice—like when he’d challenge someone to a billiards game, set a wager in which his victory meant his opponent had to come to Mass, and promptly win. He was deeply devoted to social justice and the plight of the poor, to the point that he’d forgo family vacations to serve them in Turin; meanwhile, the tongue-in-cheek nickname his best friend bestowed upon him (and that he wore happily) was Robespierre, after the Jacobin terrorist who decapitated crowds with abandon. He corralled his group of close friends to Mass and adoration; he also started referring to them as the Tipi Loschi (“sinister ones”).

Nicknamed after a terrorist, and gave his group chat an ironic and ominous name! My friends and I have a group chat named after a first-century heretic (long story)! He’s just like me. And he lived for God.

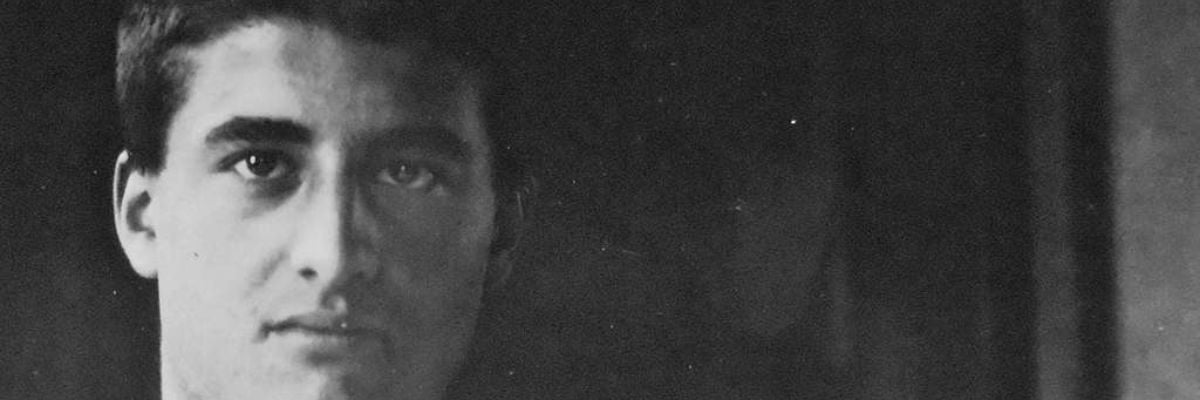

Fast-forward seven decades, and Carlo Acutis enters the scene. More striking than anything else is how ordinary he looked. Here was a boy who began attending Mass daily at seven; meticulously documented well over a hundred eucharistic miracles; and once said, “The Virgin Mary is the only woman in my life.” In the first image of him many of us saw, he was grinning at the camera in a simple red polo.

The moment I first saw that image, all of a sudden, the possibility of living a holy life became a stark, immanent reality. Oh, my gosh, he’s just like me. And he lived for God.

Thousands—maybe millions—more young Catholics react similarly upon learning that Carlo loved videogames. But here we come to a point that is not emphasized enough: he limited himself to no more than two hours of videogames a week. I’m not a gamer, but I average more than three times that amount on my phone every day. In one and the same facet of Carlo’s life, he is both eminently familiar and searingly convicting. He loved his digital entertainment (he’s just like me!) and yet exercised tremendous self-control in his consumption thereof (oh, man, I need to live like that).

Finally, Carlo’s dedication to building the kingdom through computer programming is a much-needed balm to our souls as we marinate in an influencer-choked internet. He researched, catalogued, and built a website to feature eucharistic miracles. On our darkest, doomscroll-iest days, when everything and everyone on the internet appears as stupid, dark, backwards, and banal as the Crucifixion, and we wish the internet would simply cease to exist, we do well to recall that Carlo looked at the early internet and saw nothing less than a new way to glorify God.

In the end, that’s what these two lived for: the glory of God. And they did it exactly when and where they found themselves. Thanks be to God for placing them so close in time to us, because (in my opinion) a life conformed to Christ is more jarring and convicting the less it looks like a pious holy card.

Give me the saint in sneakers and wearing a Spider-Man Halloween costume; give me the saint scaling a mountainside and goofing off with his pals. Give me a glimpse of Christ alive today.

He’s just like me . . . I need to live like that.