On June 13, Israel launched a surprise attack on key military and nuclear installations in Iran. Coming amid the ongoing armed conflict between Israelis and Palestinians, this raised the dual questions of what role the United States should play, and in which direction Christian sympathies should lie.

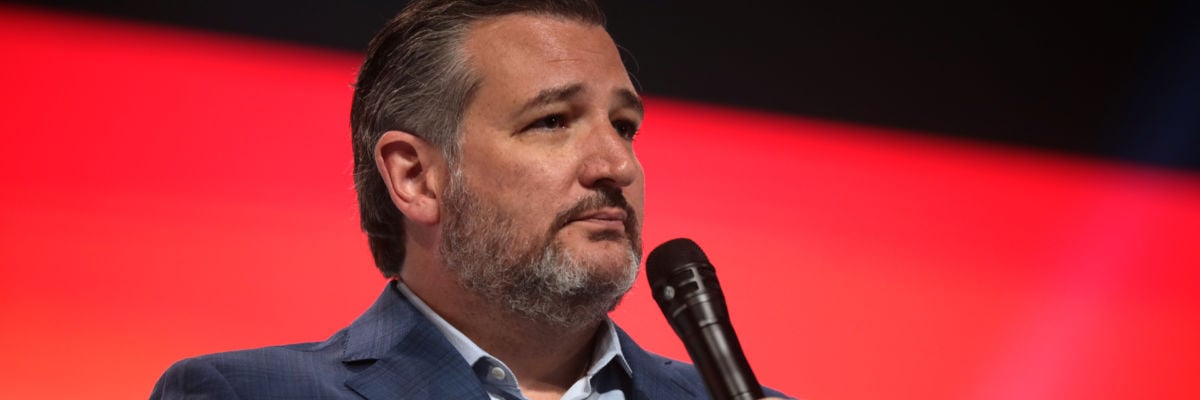

Senator Ted Cruz offered controversial answers to both of those questions when he was interviewed by Tucker Carlson. Declaring himself “the leading defender of Israel” in the U.S. Senate, Cruz explained that the “number one” reason for this is that “as a Christian growing up in Sunday school, I was taught from the Bible, those who bless Israel will be blessed, and those who curse Israel will—will be cursed. And from my perspective, I want to be on the blessing side of things.”

When Carlson asked if this was a reference to “the government of Israel,” Cruz clarified that “it says the nation of Israel. So that’s in the Bible. As a Christian, I believe that.” When pressed, Cruz couldn’t remember where in the Bible this was, leading Carlson to pounce:

It’s in Genesis. But—so you’re quoting a Bible phrase. You don’t have context for it. You don’t know where in the Bible it is. But that’s like, like, your theology. I’m confused. What does that even mean?

Carlson is right that the passage is from Genesis. More specifically, it’s from Genesis 12:1-3, in which God says to Abraham (then known as Abram):

Go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you. And I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you, and make your name great, so that you will be a blessing. I will bless those who bless you, and him who curses you I will curse; and by you all the families of the earth shall bless themselves.

So the passage says neither “the government of Israel” nor “the nation of Israel,” seeing as these words were spoken to Israel (Jacob)’s grandfather, Abraham. It is of Abraham that it is said, “I will bless those who bless you, and him who curses you I will curse.”

Nevertheless, it’s perfectly reasonable to see these covenantal promises as intended both for Abraham personally and for his descendants. After all, the prophesied “great nation” isn’t going to have a population of one. So the critical question is, which descendants of Abraham?

Many Evangelicals, particularly those of a more Dispensationalist bent, are emphatic: this is a passage about blessing Israel—both the historic kingdom of Israel created by God and the modern nation-state created by the United Nations.

After the October 7 attacks, the Southern Baptist Convention’s Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission put together an “Evangelical Statement in Support of Israel” declaring its full support for “Israel’s right and duty to defend itself against further attack.” The only biblical text mentioned in the statement (other than an allusion to Romans 13) is the ERLC applying Genesis 12 to the state of Israel.

This theology has important implications. A Chicago Council on Global Affairs-Ipsos survey from this spring (before the Israeli attacks on Iran) found that most Americans didn’t want the U.S. to side with either Israel or Palestine. That view was held by roughly two thirds of Democrats and independents and 58 percent of Americans generally. On the other hand, 58 percent of Republicans thought the U.S. should back Israel.

Regardless of political leanings and poll responses, is Genesis 12 really saying that we’re to “bless” the modern nation of Israel with military aid in its wars? Not according to St. Paul, who argues that the promises of Genesis 12 don’t automatically apply to whoever happens to share a bloodline with Abraham. Instead, they apply to whoever shares the faith of Abraham, including the faithful Gentiles (Gal. 3:7-9):

So you see that it is men of faith who are the sons of Abraham. And the scripture, foreseeing that God would justify the Gentiles by faith, preached the gospel beforehand to Abraham, saying, “In you shall all the nations be blessed.” So then, those who are men of faith are blessed with Abraham who had faith.

What Scripture does St. Paul point to in order to show that God would justify the Gentiles by faith? Genesis 12:1-3.

Whereas Southern Baptists have identified God’s covenant promises as being passed on to Abraham’s physical descendants, Paul argues that this is not how the covenant ever worked. In his words, “not all who are descended from Israel belong to Israel, and not all are children of Abraham because they are his descendants” (Rom. 9:8).

Abraham’s wife, Sarah, was elderly when God promised descendants through Abraham. When Abraham grew tired of waiting for God to fulfill his promises, he slept with Sarah’s young handmaid, Hagar, who conceived Ishmael—Abraham’s firstborn son. But God was faithful to his promises, and Sarah miraculously conceived Isaac in her old age.

In Paul’s words, “the son of the slave was born according to the flesh, the son of the free woman through promise” (Gal. 4:23). If the covenant passed on “according to the flesh” (Rom. 8:4), then it would have passed to Ishmael. Yet the covenant is instead continued through Abraham’s younger son, Isaac.

Likewise, in the next generation, the covenant continues through Isaac’s younger son, Jacob (later renamed “Israel”), after Esau (the father of the Edomites) forfeits his birthright for a bowl of lentils. So if we try to trace God’s promises to Abraham “according to the flesh,” then the covenant belongs not to Israel at all, but to Israel’s Ishmaelite or Edomite neighbors.

Instead, both the Old Testament and the New Testament present the covenant as passing on according to the promises of God. And if that’s true, then Paul is right when he says that Abraham is “the father of all who believe,” Jewish or Gentile, and says that the covenant applies to “those who share the faith of Abraham, for he is the father of us all” (Rom. 4:11-12, 16-17).

This is why John the Baptist warns his fellow Jews not to “presume to say to yourselves, ‘We have Abraham as our father’; for I tell you, God is able from these stones to raise up children to Abraham” (Matt. 3:9). And it’s why Jesus taught that “if you were Abraham’s children, you would do what Abraham did” and says, “You are of your father the devil, and your will is to do your father’s desires” (John 8:39, 44). So Abraham’s sons are the ones who keep the faith of Abraham, and it’s to us that the promises of Genesis 12 apply, not to whoever happens to be related to Abraham by flesh.

This is what Paul means in referring to the Church as “the Israel of God” in Galatians 6:16. He’s not saying that the Church is “metaphorically” Israel, or that God abandoned Israel and started a new people. He’s saying there were two groups of Israelites in his day: those who accepted the promised Messiah and those who rejected the Messiah. And God’s covenantal promises continued by faith to those who accepted the Messiah, who were then joined by faithful Gentiles, who were “grafted in” to Israel (Rom. 11:17-24). Paul reminds these Gentiles how they were once “separated from Christ” and “alienated from the commonwealth of Israel” but now have been brought near in the blood of Christ, since Christ has created people from the Jews and Gentiles in his body, the Church (Eph. 2:11-15).

Getting this right is essential for Christians. In Jeremiah 31, God promised to “make a new covenant with the house of Israel,” saying, “I will be their God, and they shall be my people” (vv. 31-34). It’s this new covenant that Christ announces at the Last Supper that he’s creating with his own blood (Luke 22:20)—a covenant with the Church, which is why it’s the Church that celebrates the Eucharist (see 1 Cor. 11:17-26). If the Church isn’t “the house of Israel,” and you treat the promises of God according to bloodline instead of faith, then the Church is without a covenant and without a Messiah.

All of this is to say that the misunderstanding of God’s covenants promoted by Senator Cruz and the Southern Baptist Convention isn’t just a bad basis for foreign policy; it’s disastrous theology, since it undermines the New Covenant itself.

Image: Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas). Credit: Gage Skidmore via Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0.