Although our salvation doesn’t depend on knowing the exact date of Christ’s birth, nor is the Church likely ever to make a dogmatic definition regarding this date, it is a matter of interest to anyone who knows and loves Jesus Christ. In this article, modern astronomy software and ancient historical documents (including but not limited to the Bible) will offer one perspective on the star of Bethlehem that heralded our Redeemer’s birth.

The three scholars who deserve the most credit for this research are Frederick Larson, Timothy Norris, and Jimmy Akin. What follows is a partial timeline of the Christ Event, from his conception in Mary’s womb to the adoration of the Magi. Powerful new software and the regularity of Kepler’s planetary motion laws offer a plausible case for the precision of each date. After this timeline, verses from the Bible and other ancient documents will provide historical support for each claim.

September, 3 B.C.

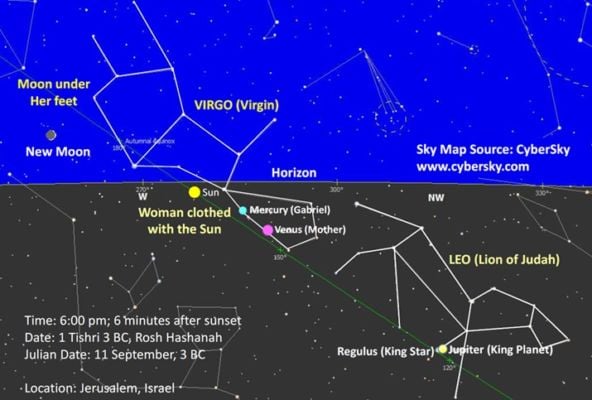

Jesus was conceived in Mary’s womb. After a close conjunction of Jupiter and Venus on August 12, Jupiter (the King Planet) began a rare triple conjunction with Regulus (the King Star), essentially crowning it with a halo pattern. The conjunction dates were Sep. 14, Feb. 17, and May 8. The celestial coronation took place in the constellation Leo. Just after sunset on Sep. 11, the constellation that rose in the east behind Leo was Virgo, the Virgin, literally “clothed with the Sun, with the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars” (Rev. 12:1). It was a new moon at her feet, coinciding with the Jewish New Year (Rosh Hashanah). The Magi, familiar with Jewish prophecies of the Messiah, definitely took notice.

June, 2 B.C.

Nine months after his conception, Jesus was born in Bethlehem. When Jupiter had finished crowning Regulus in May, it formed a close conjunction with Venus (the Mother Planet) on June 17, such that the separation between the two would have been imperceptible to the naked eye. Light from each planet added to the other, forming the most brilliant star that had ever been seen. (The Jupiter-Venus conjunction of June 17, 2 B.C. has been the brightest such conjunction in human history.) The Magi departed in haste from Babylon towards Bethlehem.

December, 2 B.C.

The first Epiphany: the Magi arrived in Bethlehem and adored the Christ child. Jupiter had proceeded ahead of the Magi, first leading them westward toward Jerusalem and then stopping (in full retrograde motion) on December 25 over the town of Bethlehem. Jesus would have been a six-month-old baby by this time, no longer in a temporary cave-stable but now in a small house built by Joseph.

At this point, let’s make the case for the claims above. The first fact to demonstrate is that King Herod died in 1 B.C., not 4 B.C. This is extremely important, because if Herod died in 4 B.C., as is widely believed, the star of Bethlehem would have appeared before then. In fact, the great mathematician and astronomer, Johannes Kepler (1571-1630), wrote two books on the subject, De stella nova (1606) and De anno natali Christi (1614). Unfortunately, he didn’t find much in the stars of 7, 6, and 5 B.C. His careful calculations could reproduce the celestial map with astonishing accuracy, but he sadly missed the star because he was searching in the wrong years.

Kepler’s mistaken idea that Herod had died in 4 B.C. was based on the historical scholarship of his time. Historian David Beyer has argued that a widely accepted reading of Josephus, which suggests that Herod died in 4 B.C., came from a transcription error introduced in a 1544 printed edition of Josephus’s Antiquities of the Jews (Book 18, chapter 4, section 106; see also David W. Beyer, “Josephus Re-examined,” available here.) According to Beyer, nearly all the pre-1544 editions and manuscripts he reviewed in the British Library and Library of Congress stated that Herod Philip (who succeeded Herod the Great) died in the twenty-second year of Tiberius’s reign. The 1544 edition, however, changed this to the twentieth year of Tiberius. The “twentieth year” reading would place Herod the Great’s death in 4 B.C. Presumably working from a post-1544 edition of Josephus, Kepler would have accepted the 4 B.C. death date.

Besides the transcription error, there are more important reasons to reject the 4 B.C. date of Herod’s death. Historian Gerard Gertoux has published a tour de force of research here, and Jimmy Akin’s findings agree with Gertoux’s. Although historian Emil Schürer’s claim that Herod died in 4 B.C. has retained widespread acceptance over the last hundred years, it rests on weak foundations. Akin critiques these foundations based on the following key points from Josephus and related evidence. He also builds a case for Herod the Great dying in 1 B.C. (specifically between the lunar eclipse on January 10, 1 B.C., and Passover on April 11, 1 B.C., likely closer to the latter).

1. Herod’s appointment as king in 40 B.C. leading to a thirty-six- or thirty-seven-year reign:

Josephus states that Herod was appointed king in the 184th Olympiad (ending mid-40 B.C.) during the consulship of Calvinus and Pollio (which began late 40 B.C.). This creates an impossible contradiction, as the dates do not overlap. External Roman sources (Appian and Dio Cassius) place the appointment in 39 B.C. Josephus reckons reigns non-inclusively (not counting partial first years in this period). Starting the count from the first full year (38 B.C.) and then adding thirty-seven years leads to a death in 1 B.C.

2. Length of reign after conquering Jerusalem (thirty-four years):

Josephus states that Herod died thirty-four years after obtaining his kingdom by slaying Antigonus (i.e., conquering Jerusalem), but he provides contradictory dates for the conquest. Some details point to 37 B.C., whereas others (e.g., exactly twenty-seven years after Pompey’s conquest in 63 B.C., and the end of 126 years of Hasmonean rule starting in 162 B.C.) point to 36 B.C. This inconsistency undermines using 37 B.C. as a firm anchor for a 4 B.C. death. However, using non-inclusive reckoning of the thirty-four-year period, we can infer a possible death date in either 2 B.C. or 1 B.C.

3. The lunar eclipse shortly before Herod’s death and Passover:

Josephus places Herod’s death between a lunar eclipse and Passover, with numerous events (requiring significant time and travel of many different people) in between. Advocates of a 4 B.C. death cite a partial lunar eclipse on March 13, 4 B.C., twenty-nine days before Passover. The twenty-nine-day gap is too short to accommodate all the events and travel Josephus describes between the eclipse and Herod’s death (estimated minimum forty-one days, more realistically sixty to ninety days). However, a total lunar eclipse occurred on Jan. 10, 1 B.C., eighty-nine days before Passover, which better matches Josephus’s description due to the sufficient time gap. Additionally, since Josephus does not specify a partial lunar eclipse, a total eclipse aligns better.

4. Evidence that Herod’s sons assumed office in 4 B.C.:

This does not prove that Herod died then, as it was common for aging rulers to appoint successors as co-rulers during their lifetime to ease succession and reduce pressure. Historical evidence shows that Herod did grant his sons governing authority before his death.

5. Testimony of the Church Fathers:

Many Church Fathers asserted a birth date of Christ in 3/2 B.C., necessitating a death date of Herod later than 4 B.C. and around 1 B.C. These Fathers included St. Irenaeus, St. Clement of Alexandria, Julius Africanus, St. Hippolytus, Eusebius, and Epiphanius, with Tertullian and Origen joining them.

Now that we’ve proven a 1 B.C. date for Herod’s death, let’s demonstrate the dates of the infant Christ’s timeline. We will proceed in chronological order:

September, 3 B.C.

The Magi weren’t just random stargazers. Most likely they were descendants of Daniel, the prophet brought to Babylon by Nebuchadnezzar. The Bible provides plenty of clues for this. In Daniel 2:48, Nebuchadnezzar makes Daniel the chief wise man (magus) of his court. In Daniel 5:11, Belshazzar’s queen reminds the king that Daniel, the chief magus, can interpret dreams and visions. In Daniel 6:28, we see that Daniel prospered in the reigns of Darius and Cyrus, implying his tremendous influence on the kingdom (including the school of magi). Daniel’s famous prophecy of weeks of years (sixty-nine sets of seven years each) in Daniel 9:24-27, predicted both the coming of Christ and the destruction of the Temple.

The point is that Daniel, a devout Jew whose God was respected and protected by King Cyrus, would have trained magi to watch the stars for signs of the Messiah. This is why the Magi took notice of the triple conjunction of Jupiter and Regulus in the constellation Leo, representing the Lion of Judah (a type of Christ mentioned in Gen. 49:8-10, 2 Sam. 7:12-14, and Rev. 5:5). It also explains how they knew the prophecy of Micah and why they wanted to worship the newborn King:

In the time of King Herod, after Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea, wise men from the East came to Jerusalem, asking, “Where is the child who has been born king of the Jews? For we observed his star at its rising, and have come to pay him homage.” When King Herod heard this, he was frightened, and all Jerusalem with him; and calling together all the chief priests and scribes of the people, he inquired of them where the Messiah was to be born. They told him, “In Bethlehem of Judea; for so it has been written by the prophet: ‘And you, Bethlehem, in the land of Judah, are by no means least among the rulers of Judah; for from you shall come a ruler who is to shepherd my people Israel” (Matt. 2:1-6).

June, 2 B.C.

The Gospel of Luke notes that John the Baptist began his ministry in the “fifteenth year of the reign of Tiberius Caesar” (Luke 3:1). Tiberius assumed the throne after Augustus died in August A.D. 14, but Roman historians such as Tacitus and Suetonius typically started counting an emperor’s regnal years from the following January 1, ignoring any partial year. Using this standard method, the fifteenth year of Tiberius would run through what we know as A.D. 29. (A regnal year is counted similarly to a person’s age: the “fifteenth year” spans from the end of the fourteenth year to the end of the fifteenth.)

Jesus began his own ministry shortly after John’s, so his public work probably started around A.D. 29 as well. Luke adds another key detail: at the start of his ministry, Jesus was “about thirty years old” (3:23). Counting back roughly thirty years from A.D. 29, and remembering there is no year zero in the transition from B.C. to A.D., we are brought to 2 B.C. as the most likely birth year.

December, 2 B.C.

In Matthew 2:9, we read, “When they had heard the king, they set out; and there, ahead of them, went the star that they had seen at its rising, until it stopped over the place where the child was.” This was the town of Bethlehem, five miles south of Jerusalem. Jupiter was in full retrograde motion that night, the first Epiphany, on December 25. This is not why December 25 was chosen to celebrate Our Lord’s Nativity each year, but it is an interesting coincidence demonstrated by modern astronomy software.

Conclusion

Although history and science can never dictate our faith, it is always helpful to see that neither history nor science can contradict it. This is because truth can’t contradict truth. If Christ entered human history through the Incarnation, it is not surprising that he would allow us to use history and science to discover his birth date.

In any case, the most important thing to contemplate as we celebrate Christmas is that “the Word became flesh and lived among us, and we have seen his glory, the glory as of a father’s only son, full of grace and truth” (John 1:14).