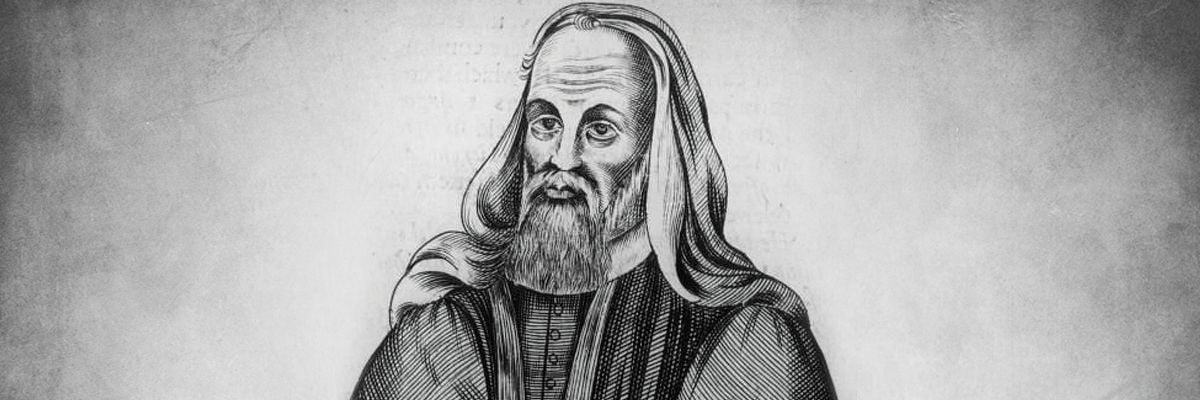

Pelagius and Pelagianism. —Pelagianism received its name from Pelagius and designates a heresy of the fifth century, which denied original sin as well as Christian grace.

I. LIFE AND WRITINGS OF PELAGIUS.—Apart from the chief episodes of the Pelagian controversy, little or nothing is known about the personal career of Pelagius. It is only after he bade a lasting farewell to Rome in A.D. 411 that the sources become more abundant; but from 418 on history is again silent about his person. As St. Augustine (De peccat. orig., xxiv) testifies that he lived in Rome “for a very long time”, we may presume that he resided there at least since the reign of Pope Anastasius (398-401). But about his long life prior to the year 400 and above all about his youth, we are left wholly in the dark. Even the country of his birth is disputed. While the most trustworthy witnesses, such as Augustine, Orosius, Prosper, and Marius Mercator, are quite explicit in assigning Britain as his native country, as is apparent from his cognomen of Brito or Britannicus, Jerome (Praef. in Jerem., lib. I and III) ridicules him as a “Scot” (loc. cit., “habet enim progeniem Scoticae gentis de Britannorum vicinia”), who being “stuffed with Scottish porridge” (Scotorum pultibus praegravatus) suffers from a weak memory. Rightly arguing that the “Scots” of those days were really the Irish, H. Zimmer (“Pelagius in Irland”, p. 20, Berlin, 1901) has recently advanced weighty reasons for the hypothesis that the true home of Pelagius must be sought in Ireland, and that he journeyed through the southwest of Britain to Rome. Tall in stature and portly in appearance (Jerome, loc. cit., “grandis et corpulentus”), Pelagius was highly educated, spoke and wrote Latin as well as Greek with great fluency and was well versed in theology. Though a monk and consequently devoted to practical asceticism, he never was a cleric; for both Orosius and Pope Zosimus simply call him a “layman”. In Rome itself he enjoyed the reputation of austerity, while St. Augustine called him even a “saintly man”, vir sanctus: with St. Paulinus of Nola (405) and other prominent bishops, he kept up an edifying correspondence, which he used later for his personal defense.

During his sojourn in Rome he composed several works: “De fide Trinitatis libri III”, now lost, but extolled by Gennadius as “indispensable reading-matter for students”; “Eclogarum ex divinis Scripturis liber unus”, in the main collection of Bible passages based on Cyprian’s “Testimoniorum libri III”, of which St. Augustine has preserved a number of fragments; “Commentarii in epistolas S. Pauli”, elaborated no doubt before the destruction of Rome by Alaric (410) and known to St. Augustine in 412: Zimmer (loc. cit.) deserves credit for having rediscovered in this commentary on St. Paul the original work of Pelagius, which had, in the course of time, been attributed to St. Jerome (P.L., XXX, 645-902). A closer examination of this work, so suddenly become famous, brought to light the fact that it contained the fundamental ideas which the Church afterwards condemned as “Pelagian heresy”. In it Pelagius denied the primitive state in paradise and original sin (cf. P.L., XXX, 678, “Insaniunt, qui de Adam per traducem asserunt ad nos venire peccatum”), insisted on the naturalness of concupiscence and the death of the body, and ascribed the actual existence and universality of sin to the bad example which Adam set by his first sin. As all his ideas were chiefly rooted in the old, pagan philosophy, especially in the popular system of the Stoics, rather than in Christianity, he regarded the moral strength of man’s will (liberum arbitrium), when steeled by asceticism, as sufficient in itself to desire and to attain the loftiest ideal of virtue. The value of Christ’s redemption was, in his opinion, limited mainly to instruction (doctrina) and example (exemplum), which the Savior threw into the balance as a counter-weight against Adam‘s wicked example, so that nature retains the ability to conquer sin and to gain eternal life even without the aid of grace. By justification we are indeed cleansed of our personal sins through faith alone (loc. cit., 663, “per solam fidem iustificat Deus impium convertendum”), but this pardon (gratia remissionis) implies no interior renovation or sanctification of the soul. How far the sola-fides doctrine “had no stouter champion before Luther than Pelagius” and whether, in particular, the Protestant conception of fiducial faith dawned upon him many centuries before Luther, as Loofs (“Realencyklopädie für protest. Theologie”, XV, 753, Leipzig, 1904) assumes, probably needs more careful investigation. For the rest, Pelagius would have announced nothing new by this doctrine, since the Antinomists of the early Apostolic Church were already familiar with “justification by faith alone” (cf. Justification); on the other hand, Luther’s boast of having been the first to proclaim the doctrine of abiding faith, might well arouse opposition. However, Pelagius insists expressly (loc. cit., 812), “Ceterum sine operibus fidei, non legis, mortua est fides”. But the commentary on St. Paul is silent on one chief point of doctrine, i.e. the significance of infant baptism, which supposed that the faithful were even then clearly conscious of the existence of original sin in children.

To explain psychologically Pelagius’s whole line of thought, it does not suffice to go back to the ideal of the wise man, which he fashioned after the ethical principles of the Stoics and upon which his vision was centered. We must also take into account that his intimacy with the Greeks developed in him, though unknown to himself, a one-sidedness, which at first sight appears pardonable. The gravest error into which he and the rest of the Pelagians fell, was that they did not submit to the doctrinal decisions of the Church. While the Latins had emphasized the guilt rather than its punishment, as the chief characteristic of original sin, the Greeks on the other hand (even Chrysostom) laid greater stress on the punishment than on the guilt. Theodore of Mopsuestia went even so far as to deny the possibility of original guilt and consequently the penal character of the death of the body. Besides, at that time, the doctrine of Christian grace was everywhere vague and undefined; even the West was convinced of nothing more than that some sort of assistance was necessary to salvation and was given gratuitously, while the nature of this assistance was but little understood. In the East, moreover, as an offset to widespread fatalism, the moral power and freedom of the will were at times very strongly or even too strongly insisted on, assisting grace being spoken of more frequently than preventing grace (see Grace). It was due to the intervention of St. Augustine and the Church, that greater clearness was gradually reached in the disputed questions and that the first impulse was given towards a more careful development of the dogmas of original sin and grace (ef. Mausbach, “Die Ethik des hl. Augustinus”, II, 1 sqq., Freiburg, 1909).

II. PELAGIUS AND CAELESTIUS (411-5).—Of far-reaching influence upon the further progress of Pelagianism was the friendship which Pelagius contracted in Rome with Clestius, a lawyer of noble (probably Italian) descent. A eunuch by birth, but endowed with no mean talents, Caelestius had been won over to asceticism by his enthusiasm for the monastic life, and in the capacity of a lay-monk he endeavored to convert the practical maxims learnt from Pelagius, into theoretical principles, which he successfully propagated in Rome. St. Augustine, while charging Pelagius with mysteriousness, mendacity, and shrewdness, calls Caelestius (De peccat. orig., xv) not only “incredibly loquacious”, but also open-hearted, obstinate, and free in social intercourse. Even if their secret or open intrigues did not escape notice, still the two friends were not molested by the official Roman circles. But matters changed when in 411 they left the hospitable soil of the metropolis, which had been sacked by Alaric (410), and set sail for North Africa. When they landed on the coast near Hippo, Augustine, the bishop of that city, was absent, being fully occupied in settling the Donatist disputes in Africa. Later, he met Pelagius in Carthage several times, without, however, coming into closer contact with him. After a brief sojourn in North Africa, Pelagius travelled on to Palestine, while Caelestius tried to have himself made a presbyter in Carthage. But this plan was frustrated by the deacon Paulinus of Milan, who submitted to the bishop, Aurelius, a memorial in which six theses of Caelestius—perhaps literal extracts from his lost work “Contra traducem peccati”—were branded as heretical. These theses ran as follows: (I) Even if Adam had not sinned, he would have died. (2) Adam‘s sin harmed only himself, not the human race. (3) Children just born are in the same state as Adam before his fall. (4) The whole human race neither dies through Adam‘s sin or death, nor rises again through the resurrection of Christ. (5) The (Mosaic) Law is as good a guide to heaven as the Gospel. (6) Even before the advent of Christ there were men who were without sin. On account of these doctrines, which clearly contain the quintessence of Pelagianism, Caelestius was summoned to appear before a synod at Carthage (411); but he refused to retract them, alleging that the inheritance of Adam‘s sin was an open question and hence its denial was no heresy. As a result he was not only excluded from ordination, but his six theses were condemned. He declared his intention of appealing to the pope in Rome, but without executing his design went to Ephesus in Asia Minor, where he was ordained a priest.

Meanwhile the Pelagian ideas had infected a wide area, especially around Carthage, so that Augustine and other bishops were compelled to take a resolute stand against them in sermons and private conversations. Urged by his friend Marcellinus, who “daily endured the most annoying debates with the erring brethren”, St. Augustine in 412 wrote the two famous works: “De peccatorum meritis et remissione libri III” (P.L., XLIV, 109 sqq.) and “De spiritu et litera” (ibid., 201 sqq.), in which he positively established the existence of original sin, the necessity of infant baptism, the impossibility of a life without sin, and the necessity of interior grace (spiritus) in opposition to the exterior grace of the law (litera). When in 414 disquieting rumors arrived from Sicily and the so-called “Definitiones Caelestii” (reconstructed in Gamier, “Marii Mercatoris Opera”, I, 384 sqq., Paris, 1673), said to be the work of Caelestius, were sent to him, he at once (414 or 415) published the rejoinder, “De perfectione justitiae hominis” (P.L., XLIV, 291 sqq.), in which he again demolished the illusion of the possibility of complete freedom from sin. Out of charity and in order to win back the erring the more effectually, Augustine, in all these writings, never mentioned the two authors of the heresy by name.

Meanwhile Pelagius, who was sojourning in Palestine, did not remain idle; to a noble Roman virgin, named Demetrias, who at Alaric’s coming had fled to Carthage, he wrote a letter which is still extant (in P.L., XXX, 15-45) and in which he again inculcated his Stoic principles of the unlimited energy of nature. Moreover, he published in 415 a work, now lost, “De natura”, in which he attempted to prove his doctrine from authorities, appealing not only to the writings of Hilary and Ambrose, but also to the earlier works of Jerome and Augustine, both of whom were still alive. The latter answered at once (415) by his treatise “De natura et gratia” (P.L., XLIV, 247 sqq.). Jerome, however, to whom Augustine’s pupil Orosius, a Spanish priest, personally explained the danger of the new heresy, and who had been chagrined by the severity with which Pelagius had criticized his commentary on the Epistle to the Ephesians, thought the time ripe to enter the lists; this he did by his letter to Ctesiphon (Ep. cxxliii) and by his graceful “Dialogus contra Pelagianos” (P.L., XXIII, 495 sqq.). He was assisted by Orosius, who, forthwith accused Pelagius in Jerusalem of heresy. Thereupon, Bishop John of Jerusalem “dearly loved” (St. Augustine, “Ep. clxxix”) Pelagius and had him at the time as his guest. He convoked in July, 415, a diocesan council for the investigation of the charge. The proceedings were hampered by the fact that Orosius, the accusing party, did not understand Greek and had engaged a poor interpreter, while the defendant Pelagius was quite able to defend himself in Greek and uphold his orthodoxy. However, according to the personal account (written at the close of 415) of Orosius (Liber apolog. contra Pelagium, P.L., XXXI, 1173), the contesting parties at last agreed to leave the final judgment on all questions to the Latins, since both Pelagius and his adversaries were Latins, and to invoke the decision of Innocent I; meanwhile silence was imposed on both parties.

But Pelagius was granted only a short respite. For in the very same year, the Gallic bishops, Heros of Arles and Lazarus of Aix, who, after the defeat of the usurper Constantine (411), had resigned their bishoprics and gone to Palestine, brought the matter before Bishop Eulogius of Caesarea, with the result that the latter summoned Pelagius in December, 415, before a synod of fourteen bishops, held in Diospolis, the ancient Lydda. But fortune again favored the heresiarch. About the proceedings and the issue we are exceptionally well informed through the account of St. Augustine, “De gestis Pelagii” (P.L., XLIV, 319 sqq.), written in 417 and based on the acts of the synod. Pelagius punctually obeyed the summons, but the principal complainants, Heros and Lazarus, failed to make their appearance, one of them being prevented by ill-health. And as Orosius, too, derided and persecuted by Bishop John of Jerusalem, had departed, Pelagius met no personal plaintiff, while he found at the same time a skillful advocate in the deacon Anianus of Celeda (cf. Hieronym., “Ep. cxliii”, ed. Vallarsi, I, 1067). The principal points of the petition were translated by an interpreter into Greek and read only in an extract. Pelagius, having won the good-will of the assembly by reading to them some private letters of prominent bishops—among them one of Augustine (Ep. cxlvi)—began to explain away and disprove the various accusations. Thus from the charge that he made the possibility of a sinless life solely dependent on free will, he exonerated himself by saying that, on the contrary, he required the help of God (adjutorium Dei) for it, though by this he meant nothing else than the grace of creation (gratia creationis). Of other doctrines with which he had been charged, he said that, formulated as they were in the complaint, they did not originate from him, but from Caelestius, and that he also repudiated them. After this hearing there was nothing left for the synod but to discharge the defendant and to announce him as worthy of communion with the Church. The Orient had now spoken twice and had found nothing to blame in Pelagius, because he had hidden his real sentiments from his judges.

III. CONTINUATION AND END OF THE CONTROVERSY (415-8).—The new acquittal of Pelagius did not fail to cause excitement and alarm in North Africa, whither Orosius had hastened in 416 with letters from Bishops Heros and Lazarus. To parry the blow, something decisive had to be done. In autumn, 416, 67 bishops from Proconsular Africa assembled in a synod at Carthage, which was presided over by Aurelius, while fifty-nine bishops of the ecclesiastical province of Numidia, to which the See of Hippo, St. Augustine’s see, belonged, held a synod in Mileve. In both places the doctrines of Pelagius and Caelestius were again rejected as contradictory to the Catholic faith. However, in order to secure for their decisions “the authority of the Apostolic See“, both synods wrote to Innocent I, requesting his supreme sanction. And in order to impress upon him more strongly the seriousness of the situation, five bishops (Augustine, Aurelius, Alypius, Evodius, and Possidius) forwarded to him a joint letter, in which they detailed the doctrine of original sin, infant baptism, and Christian grace (St. Augustine, “Epp. clxxv-vii”). In three separate epistles, dated January 27, 417, the pope answered the synodal letters of Carthage and Mileve as well as that of the five bishops (Jaffé, “Regest.”, 2nd ed., nn. 321-323, Leipzig, 1885). Starting from the principle that the resolutions of provincial synods have no binding force until they are confirmed by the supreme authority of the Apostolic See, the pope developed the Catholic teaching on original sin and grace, and excluded Pelagius and Caelestius, who were reported to have rejected these doctrines, from communion with the Church until they should come to their senses (donec resipiscant). In Africa, where the decision was received with unfeigned joy, the whole controversy was now regarded as closed, and Augustine, on September 23, 417, announced from the pulpit (Serm., cxxxi, 10, in P.L., XXXVIII, 734), “Jam de hac causa duo concilia missa stint ad Sedem apostolicam, inde etiam rescripta venerunt; causa finita est”. (Two synods have written to the Apostolic See about this matter; the replies have come back; the question is settled.) But he was mistaken; the matter was not yet settled.

Innocent I died on March 12, 417, and Zosimus, a Greek by birth, succeeded him. Before his tribunal the whole Pelagian question was now opened once more and discussed in all its bearings. The occasion for this was the statements which both Pelagius and Caelestius submitted to the Roman See in order to justify themselves. Though the previous decisions of Innocent I had removed all doubts about the matter itself, yet the question of the persons involved was undecided, viz. Did Pelagius and Caelestius really teach the theses condemned as heretical? Zosimus‘ sense of justice forbade him to punish any one with excommunication before he was duly convicted of his error. And if the steps recently taken by the two defendants were considered, the doubts which might arise on this point, were not wholly groundless. In 416 Pelagius had published a new work, now lost, “De libero arbitrio libri IV”, which in its phraseology seemed to verge towards the Augustinian conception of grace and infant baptism, even if in principle it did not abandon the author’s earlier standpoint. Speaking of Christian grace, he admitted not only a Divine revelation, but also a sort of interior grace, viz. an illumination of the mind (through sermons, reading of the Bible, etc.), adding, however, that the latter served not to make salutary works possible, but only to facilitate their performance. As to infant baptism he granted that it ought to be administered in the same form as in the case of adults, not in order to cleanse the children from a real original guilt, but to secure to them entrance into the “kingdom of God“. Unbaptized children, he thought, would after their death be excluded from the “kingdom of God“, but not from “eternal life”. This work, together with a still extant confession of faith, which bears witness to his childlike obedience, Pelagius sent to Rome, humbly begging at the same time that chance inaccuracies might be corrected by him who “holds the faith and the see of Peter”. All this was addressed to Innocent I, of whose death Pelagius had not yet heard. Caelestius, also, who meanwhile had changed his residence from Ephesus to Constantinople, but had been banished thence by the anti-Pelagian Bishop Atticus, took active steps towards his own rehabilitation. In 417 he went to Rome in person and laid at the feet of Zosimus a detailed confession of faith (Fragments, P.L., XLV, 1718), in which he affirmed his belief in all doctrines, “from the Trinity of one God to the resurrection of the dead” (cf. St. Augustine, “De peccato orig.”, xxiii).

Highly pleased with this Catholic faith and obedience, Zosimus sent two different letters (P.L., XLV, 1719 sqq.) to the African bishops, saying that in the case of Caelestius Bishops Heros and Lazarus had proceeded without due circumspection, and that Pelagius too, as was proved by his recent confession of faith, had not swerved from the Catholic truth. As to Caelestius, who was then in Rome, the pope charged the Africans either to revise their former sentence or to convict him of heresy in his own (the pope’s) presence within two months. The papal command struck Africa like a bomb-shell. In great haste a synod was convened at Carthage in November, 417, and writing to Zosimus, they urgently begged him not to rescind the sentence which his predecessor, Innocent I, had pronounced against Pelagius and Caelestius, until both had confessed the necessity of interior grace for all salutary thoughts, words, and deeds. At last Zosimus came to a halt. By a rescript of March 21, 418, he assured them that he had not yet pronounced definitively, but that he was transmitting to Africa all documents bearing on Pelagianism in order to pave the way for a new, joint investigation. Pursuant to the papal command, there was held on May 1, 418, in the presence of 200 bishops, the famous Council of Carthage, which again branded Pelagianism as a heresy in eight (or nine) canons (Denzinger, “Enchir.”, 10th ed., 1908, 101-8). Owing to their importance they may be summarized: (I) Death did not come to Adam from a physical necessity, but through sin. (2) New-born children must be baptized on account of original sin. (3) Justifying grace not only avails for the forgiveness of past sins, but also gives assistance for the avoidance of future sins. (4) The grace of Christ not only discloses the knowledge of God‘s commandments, but also imparts strength to will and execute them. (5) Without God‘s grace it is not merely more difficult, but absolutely impossible to perform good works. Not out of humility, but in truth must we confess ourselves to be sinners. (7) The saints refer the petition of the Our Father, “Forgive us our trespasses”, not only to others, but also to themselves. (8) The saints pronounce the same supplication not from mere humility, but from truthfulness. Some codices contain a ninth canon (Denzinger, loc. cit., note 3): Children dying without baptism do not go to a “middle place” (medius locus), since the non-reception of baptism excludes both from “the kingdom of heaven” and from “eternal life”. These clearly-worded canons, which (except the last-named) afterwards came to be articles of faith binding the universal Church, gave the death-blow to Pelagianism; sooner or later it would bleed to death.

Meanwhile, urged by the Africans (probably through a certain Valerian, who as comes held an influential position in Ravenna), the secular power also took a hand in the dispute, the Emperor Honorius, by rescript of April 30, 418, from Ravenna, banishing all Pelagians from the cities of Italy. Whether Caelestius evaded the hearing before Zosimus, to which he was now bound, “by fleeing from Rome” (St. Augustine, “Contra duas epist. Pelag.”, II, 5), or whether he was one of the first to fall a victim to the imperial decree of exile, cannot be satisfactorily settled from the sources. With regard to his later life, we are told that in 421 he again haunted Rome or its vicinity, but was expelled a second time by an imperial rescript (cf. P.L., XLV, 1750). It is further related that in 425 his petition for an audience with Celestine I was answered by a third banishment (cf. P.L., LI, 271). He then sought refuge in the Orient, where we shall meet him later. Pelagius could not have been included in the imperial decree of exile from Rome. For at that time he undoubtedly resided in the Orient, since, as late as the summer of 418, he communicated with Pinianus and his wife Melania, who lived in Palestine (cf. Card. Rampolla, “Santa Melania giuniore”, Rome, 1905). But this is the last information we have about him; he probably died in the Orient. Having received the Acts of the Council of Carthage, Zosimus sent to all the bishops of the world his famous “Epistola tractoria” (418) of which unfortunately only fragments have come down to us. This papal encyclical, a lengthy document, gives a minute account of the entire “causa Caelestii et Pelagii”, from whose works it quotes abundantly, and categorically demands the condemnation of Pelagianism as a heresy. The assertion that every bishop of the world was obliged to confirm this circular by his own signature, cannot be proved, it is more probable that the bishops were required to transmit to Rome a written agreement; if a bishop refused to sign, he was deposed from his office and banished. A second and harsher rescript, issued by the emperor on June 9, 419, and addressed to Bishop Aurelius of Carthage (P.L., XLV, 1731), gave additional force to this measure. Augustine’s triumph was complete. In 418, drawing the balance, as it were, of the whole controversy, he wrote against the heresiarchs his last great work, “De gratia Christi et de peccato originali” (P.L., XLIV, 359 sqq.).

IV.—THE DISPUTE OF ST. AUGUSTINE WITH JULIAN OF ECLANUM (419-28).—Through the vigorous measures adopted in 418, Pelagianism was indeed condemned, but not crushed. Among the eighteen bishops of Italy who were exiled on account of their refusal to sign the papal decree, Julian, Bishop of Eclanum, a city of Apulia now deserted, was the first to protest against the “Tractoria” of Zosimus. Highly educated and skilled in philosophy and dialectics, he assumed the leadership among the Pelagians. But to fight for Pelagianism now meant to fight against Augustine. The literary feud set in at once. It was probably Julian himself who denounced St. Augustine as damnator nuptiarum to the influential comes Valerian in Ravenna, a nobleman, who was very happily married. To meet the accusation, Augustine wrote, at the beginning of 419, an apology, “De nuptiis et concupiscentia libri II” (P.L., XLIV, 413 sqq.) and addressed it to Valerian. Immediately after (419 or 420), Julian published a reply which attacked the first book of Augustine’s work and bore the title, “Libri IV ad Turbantium”. But Augustine refuted it in his famous rejoinder, written in 421 or 422, “Contra Iulianum libri VI” (P.L., XLIV, 640 sqq.). When two Pelagian circulars, written by Julian and scourging the “Manichaean views” of the Antipelagians, fell into his hands, he attacked them energetically (420 or 421) in a work, dedicated to Boniface I, “Contra duas epistolas Pelagianorum libri IV” (P.L., XLIV, 549 sqq.). Being driven from Rome, Julian had found (not later than 421) a place of refuge in Cilicia with Theodore of Mopsuestia. Here he employed his leisure in elaborating an extensive work, “Libri VIII ad Florum”, which was wholly devoted to refuting the second book of Augustine’s “De nuptiis et concupiscentia”. Though composed shortly after 421, it did not come to the notice of St. Augustine until 427. The latter’s reply, which quotes Julian’s argumentations sentence for sentence and refutes them, was completed only as far as the sixth book, whence it is cited in patristic literature as “Opus imperfectum contra Iulianum” (P.L., XLV, 1049 sqq.). A comprehensive account of Pelagianism, which brings out into strong relief the diametrically opposed views of the author, was furnished by Augustine in 428 in the final chapter of his work, “De haeresibus” (P.L., XLII, 21 sqq.). Augustine’s last writings published before his death (430) were no longer aimed against Pelagianism, but against Semipelagianism.

After the death of Theodore of Mopsuestia (428), Julian of Eclanum left the hospitable city of Cilicia and in 429 we meet him unexpectedly in company with his fellow exiles Bishops Florus, Orontius, and Fabius, at the Court of the Patriarch Nestorius of Constantinople, who willingly supported the fugitives. It was here, too, in 429, that Caelestius emerged again as the protégé of the patriarch; this is his last appearance in history; for from now on all trace of him is lost. But the exiled bishops did not long enjoy the protection of Nestorius. When Marius Mercator, a layman and friend of St. Augustine, who was then present in Constantinople, heard of the machinations of the Pelagian in the imperial city he composed towards the end of 429 his “Commonitorium super nomine Caelestii” (P.L., XLVIII, 63 sqq.), in which he exposed the shameful life and the heretical character of Nestorius’ wards. The result was that the Emperor Theodosius II decreed their banishment in 430. When the Oecumenical Council of Ephesus (431) repeated the condemnation pronounced by the West (cf. Mansi, “Concil. collect.”, IV, 1337), Pelagianism was crushed in the East. According to the trustworthy report of Prosper of Aquitaine (“Chronic.”, ad a. 439, in P.L., LI, 598), Julian of Eclanum, feigning repentance, tried to regain possession of his former bishopric, a plan which Sixtus III (432-40) courageously frustrated. The year of his death is uncertain. He seems to have died in Italy between 441 and 455 during the reign of Valentinian III.

V. LAST TRACES OF PELAGIANISM (429-529.)—After the Council of Ephesus (431), Pelagianism no more disturbed the Greek Church, so that the Greek historians of the fifth century do not even mention either the controversy or the names of the heresiarchs. But the heresy continued to smoulder in the West and died out very slowly. The main centers were Gaul and Britain. About Gaul we are told that a synod, held probably at Troyes in 429, was compelled to take steps against the Pelagians. It also sent Bishops Germanus of Auxerre and Lupus of Troyes to Britain to fight the rampant heresy, which received powerful support from two pupils of Pelagius, Agricola and Fastidius (cf. Caspari, “Letters, Treatises and Sermons from the two last Centuries of Ecclesiastical Antiquity”, pp. 1-167, Christiania, 1891). Almost a century later, Wales was the center of Pelagian intrigues. For the saintly Archbishop David of Menevia participated in 519 in the Synod of Brefy, which directed its attacks against the Pelagians residing there, and after he was made Primate of Cambria, he himself convened a synod against them. In Ireland also Pelagius’s “Commentary on St. Paul”, described in the beginning of this article, was in use long afterwards, as is proved by many Irish quotations from it. Even in Italy traces can be found, not only in the Diocese of Aquileia (cf. Garnier, “Opera Marii Mercat.”, I, 319 sqq., Paris, 1673), but also in Middle Italy; for the so-called “Liber Priedestinatus”, written about 440 perhaps in Rome itself, bears not so much the stamp of Semipelagianism as of genuine Pelagianism (cf. von Schubert, “Der sog. Praedestinatus, ein Beitrag zur Geschichte des Pelagianismus”, Leipzig, 1903). A more detailed account of this work will be found under the article Predestinarianism. It was not until the Second Synod of Orange (529) that Pelagianism breathed its last in the West, though that convention aimed its decisions primarily against Semipelagianism (q.v.).

JOSEPH POHLE