Audio only:

Liberal scholars like Bart Ehrman can make it sound like scholars have concluded that the Gospels were written in the late first (and perhaps early second) century. But they can also misrepresent things.

Some conservative scholars do date the Gospels to the late first century, and some liberal scholars date them quite early.

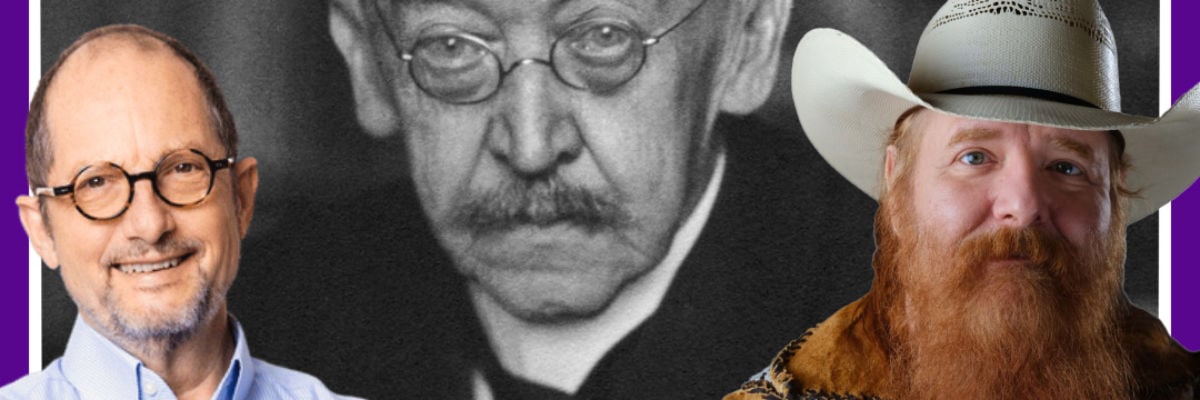

In this episode, Jimmy Akin reveals how one liberal scholar—Adolf von Harnack—followed the evidence and concluded that Matthew, Mark, and Luke were all written within just a few decades of the time of Christ!

TRANSCRIPT:

Coming Up

The four Gospels—Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John—are key documents for the Christian faith.

But when were they written?

Some scholars say late in the first century, and maybe even into the second.

But others hold they were written only 20 to 30 years after the ministry of Jesus.

And you don’t have to be a theological conservative to hold that view.

Some of the people who hold it have been famous liberals.

Let’s get into it!

* * *

Howdy, folks!

You can help me keep making this podcast—and you can get early access to new episodes—by going to Patreon.com/JimmyAkinPodcast

Introduction

Back in Episode 43 of The Jimmy Akin Podcast, I responded to some arguments about the Gospels made by Robyn Walsh, who is a member of Bart Ehrman’s team.

Robyn held that the earliest Gospel—Mark—was written no earlier than A.D. 70, and that Matthew, Luke, and John were written in the 80s and 90s or even later in the case of John.

Bart Ehrman himself gives similar dates, though he has been open to Mark being written at the end of the 60s, and here is what he recently said when asked about this question.

INTERVIEWER: So when do scholars think that the gospels were written?

BART EHRMAN: Well, the critical scholars who are not like conservative evangelical fundamentalists or conservative Catholics or Jesus scholars of various kinds have pretty well agreed on the dates. As it turns out. I mean, pretty much everybody who would teach in universities and things would say that Mark was probably the first gospel written around their 70. Luke and John, I mean, Luke and Matthew are later. Matthew May be a little bit earlier, but sometime in the eighties, 80 to 85, John, the last gospel, 90 to 95, those dates aren’t really particularly controversial, although they’re always, of course you’re going to have scholars come along saying, no, no, that’s not right. Or they’ll redate things or do, but basically that’s pretty much the consensus and I think they’re good grounds for it.

Here he says Mark was written “around the year 70”—so just before or just after.

And notice how he partitions the scholars he’s talking about.

BART: Critical scholars who are not like conservative evangelical fundamentalists, who are conservative Catholics, pretty much everybody who would teach in universities.

So Bart’s not talking about conservative Protestant or conservative Catholic scholars.

And—by excluding people from conservative points of view—he’s thus talking about people who come from the other end of the spectrum he’s using.

In other words, he’s talking about liberal scholars—whether they’re liberal Protestants, liberal Catholics, liberal atheists, liberal agnostics, or what have you.

He’s also getting into dicey territory by identifying these as the kind of people who teach in universities, because conservative scholars also teach in universities.

And he’s misleadingly implying that the dates held by conservative scholars differ significantly. In fact, there are a lot of conservative Protestants and Catholics who date the Gospels to from around 70 to the mid-90s.

Back in Episode 43, I pointed out some of the flaws with the arguments that Robyn used for her dates, and I said that in future episodes I’d give you my own arguments for when they should be dated.

I’ll still do that, but first I wanted to devote an episode to someone else’s ideas.

Because, as Bart said,

BART: They’re always, of course, you’re going to have scholars come along, say, no, no, that’s not right. Or the redate things.

And that’s true.

In fact, some of them are liberal. Like Adolf von Harnack.

Who Was Adolf von Harnack?

Adolf von Harnack was born in 1851 in what is now Estonia. He was of German heritage, and he passed on to his reward in 1930 in Heidelberg in what is now Germany—at the age of 79.

He was one of the foremost Church historians of his age, and he was also a Protestant theologian.

Specifically, he was a liberal Protestant. The Dictionary of Historical Theology states:

Dictionary of Historical Theology

As early as his student days Harnack had begun to move away from the Christian orthodoxy propounded both by his father and most of his academic teachers. He argued that clarity about the truth of Christian faith would only be gained through a consistently historical approach—an approach that reflected the influence of Albrecht Ritschl, with whose theology Harnack aligned himself closely. . . .

Harnack drew conclusions with respect to some dogmatic questions (e.g. the resurrection, the significance of the historical Jesus) which were vehemently rejected by the Lutheran Church. . . .

His lectures on the “essence of Christianity,” delivered in the winter semester of 1899–1900 in Berlin and quickly appearing in book form ([as] What is Christianity?), had an immediate and sensational impact. It was Harnack’s intention to expound the Christian faith in a comprehensible way, and with due regard for modern living. The “Gospel of Jesus,” understood to be the original, pure doctrinal heart of Christian faith, was the focal point of his exposition. In a very short time, the book went through twenty editions. An English translation appeared in the same year as the German original. It remains a classic document of the theology of Liberal Protestantism in Germany.

So, von Harnack was no conservative. He was one of the key figures in liberal Protestantism in the early 20th century.

But that didn’t mean that he adopted any and every view that was favored in liberal circles.

He was willing to do independent thinking, and one of the subjects he came to some conclusions on that surprised his liberal colleagues was the date of the Synoptic Gospels—Matthew, Mark, and Luke.

He’s one of several liberal scholars who have reached such conclusions by following the evidence. Others include John A.T. Robinson and Maurice Casey.

My own views on the Synoptic Gospels are largely similar to von Harnack’s.

They’re not identical, but they are similar.

So I thought I’d do an episode showing you how even a liberal scholar who is openminded to the evidence can be convinced that they had early dates.

Von Harnack on Acts

In 1911, von Harnack published a book titled The Date of the Acts and of The Synoptic Gospels.

In it, he starts by dating the book of Acts, which is the sequel to the Gospel of Luke, and he says:

The Date of the Acts and of the Synoptic Gospels

The conclusion of the Acts (28:30, 31) must always form the starting-point for an attempt to ascertain the date of the work; it runs as follows:

[Paul] lived there [in Rome] two whole years at his own expense, and welcomed all who came to him, proclaiming the kingdom of God and teaching about the Lord Jesus Christ with all boldness and without hindrance (ESV).

The significance of those verses may not leap out at you unless you’re familiar with the structure of Acts.

Basically, the book is 28 chapters long. Chapters 1 to 12 focus on St. Peter, while chapters 13 to 28 focus on St. Paul.

A major turning point in the Paul section occurs in chapter 21, when he returns to Jerusalem after a long absence.

But not all is going to go well, because people have been warning Paul with prophecies that if he goes back to Jerusalem, he will be arrested.

He is arrested, and there is a series of really dramatic events that almost cost him his life.

He ends up awaiting trial in the nearby town of Caesarea Maritima, where the Romans had their local headquarters.

And, boy, does he have to wait! He has to wait years—partly because the Roman governor Felix wants Paul to give him a bribe to let him go—which Paul won’t do—and partly because Felix wants to do the Jews a favor, so he lets Paul rot waiting for his trial.

But then—in chapter 25—Felix is replaced by the new governor, Festus, and Festus is a man of action!

He’s going to make sure Paul gets his trial speedily, and since the charges against Paul have to do with the Jewish religion, he offers Paul the chance to be tried by his own people.

Only knowing the Jewish sentiment against him, that’s one offer Paul is determined not to accept.

So Paul uses a legal stratagem and invokes his right as a Roman citizen to have his case heard by the emperor—who was the Emperor Nero at this time—so Festus is legally boxed in, and he declares:

Acts 25:12, ESV

“To Caesar you have appealed; to Caesar you shall go.”

Festus thus arranges to have Paul extradited to Rome, which means a long sea voyage across the Mediterranean.

So sit right back and you’ll hear a tale—a tale of a fateful trip.

It was getting late in the year now, and the season it was safe to sail in the Mediterranean was ending.

The weather started getting rough. The tiny ship was tossed. If not for the courage of the fearless crew—well, actually the crew wasn’t fearless.

The mate was not a mighty sailing man. The skipper was not brave and sure.

In fact, the crew tried to steal the dinghy and abandon the passengers and cargo on the ship, which actually wasn’t tiny. It held 276 people plus a cargo of wheat.

But Paul knew what the crew was up to and warned the Roman centurion escorting him to Rome.

The centurion had his soldiers cut the ropes holding the dinghy to the ship and let it float off, so the crew wasn’t able to use it to abandon the passengers and escape.

Soon they realized that they were going to shipwreck!

Paul had them jettison the ship’s cargo of wheat to lighten the ship.

And then, wham!

The ship set ground on the shore of this uncharted desert isle.

Only really, it was the island of Malta.

So this is the tale of the castaways. They’re here for a long, long time.

They had to make the best of things. It’s an uphill climb.

No phone, no lights, no motor car. Not a single luxury.

Like Robinson Crusoe—as primitive as can be.

It was raining and cold when they washed up on the beach.

Paul got bit by a snake, but he didn’t die.

In fact, he ended up healing the father of the head man of the island, who was named Publius.

Publius’s father was sick with fever and dysentery—which was pretty embarrassing. You can look that up if you want to know what it is.

And because it’s now winter and unsafe to sail, they end up spending months on the island.

But when Spring finally comes, they’re able to cross to the mainland of Italy.

They then gradually work their way up toward Rome.

They meet some fellow Christians on the way.

And then they finally arrive in Rome, so Paul can finally have his trial.

And this is before the Fire of Rome when Nero turned against Christians, so Paul has every expectation of being set free since the charges against him are from Jewish law rather than Roman law—and he’s innocent anyway.

So things are looking good! Yay! And Luke writes:

Acts 28:30-31, ESV

[Paul] lived there [in Rome] two whole years at his own expense, and welcomed all who came to him, proclaiming the kingdom of God and teaching about the Lord Jesus Christ with all boldness and without hindrance.

The end.

Wait. What?

Paul has been under arrest since chapter 21 of the book. We’ve just spent a quarter of the entire book of Acts building up to Paul’s trial before Nero, and Luke suddenly bails on us and doesn’t give us closure by telling us what happened?

He just ends with Paul under house arrest for two years?

Why?

Well, that’s one of the things that occurred to Adolf von Harnack, too, and he writes:

The Date of the Acts and of the Synoptic Gospels

Tremendous difficulties present themselves. We cannot make too much of them. Throughout eight whole chapters, St. Luke keeps his readers intensely interested in the progress of the trial of St. Paul, simply that he may in the end completely disappoint them—they learn nothing of the final result of the trial!

Such a procedure is scarcely less indefensible than that of one who might relate the history of our Lord and close the narrative with his delivery to Pilate, because Jesus had now been brought up to Jerusalem and had made his appearance before the chief magistrate in the capital city!

Yeah, that wouldn’t really be a good conclusion for the Gospels. After repeatedly predicting his death and resurrection, Jesus makes his final journey to Jerusalem, gets arrested, and then before he has his trial—the end!

Not a good ending at all.

Von Harnack thus concludes:

The Date of the Acts and of the Synoptic Gospels

The more clearly we see that the trial of St. Paul, and above all his appeal to Caesar, is the chief subject of the last quarter of the Acts, the more hopeless does it appear that we can explain why the narrative breaks off as it does, otherwise than by assuming that the trial had actually not yet reached its close. It is no use to struggle against this conclusion. If St. Luke, in the year 80, 90, or 100, wrote thus he was not simply a blundering but an absolutely incomprehensible historian!

As well as a terrible storyteller.

So von Harnack concludes that Acts was written at the end of the 2-year period of house arrest in Rome and that the trial before Nero had not yet reached its conclusion.

He also has other considerations pointing to an early date for Acts, but this is the most decisive one for him—and for me.

Von Harnack dates this to the year A.D. 62. I would put it in A.D. 60, but we both agree that this is when Acts was written.

Von Harnack on Luke

Yeah, yeah, yeah, book of Acts, I hear some saying. What about the Gospels? That’s what I’m here for.

Okay, here’s the deal. Acts is the sequel to the Gospel of Luke, so Luke should have been written before it.

So the arguments favoring the idea that Acts was written around A.D. 60 or 62—when St. Paul was still alive—now also apply to the Gospel of Luke, and von Harnack writes:

The Date of the Acts and of the Synoptic Gospels

Strong arguments, which favor the composition of the Acts before 70 a.d., now also apply in their full force to the gospel of St Luke, and it seems now to be established beyond question that both books of this great historical work were written while St. Paul was still alive (emphasis in original).

Von Harnack doesn’t give us a specific year for Luke, but it would presumably be earlier than Acts, which von Harnack places in 62.

And the date of Luke gives us a basis for dating one of the other Gospels.

Von Harnack on Mark

The reason is—as von Harnack explains—that

The Date of the Acts and of the Synoptic Gospels

There is no doubt that St. Mark’s gospel belongs to the sources of the gospel of St. Luke.

So if Luke used Mark in composing his Gospel, then Mark must have been written before Luke.

But rather than just concluding that, von Harnack looks at both the internal and the external evidence for Mark.

Internal evidence is what you can deduce by reading the Gospel itself: Does Mark contain any clues about when it was written?

While external evidence is what you can deduce by reading other early pieces of Christian literature that mention Mark: What do they imply about when it was written?

On the internal evidence, von Harnack concludes:

The Date of the Acts and of the Synoptic Gospels

The gospel itself gives absolutely no direct indication as to its date; one thing only is clear from chap. 13 . . . that it was written before the destruction of Jerusalem; how many years before there is absolutely no internal evidence to show. Internal indications, therefore, place no impediment in the way of assigning St. Mark at the latest to the sixth decade of the first century, as is required by the date we have assigned to St. Luke (emphasis in original).

Mark 13 is the chapter where Jesus predicts the destruction of the temple in Jerusalem, and I think von Harnack is right that the way this chapter is written shows that it was written before the destruction of Jerusalem.

Von Harnack thus concludes that there’s no barrier to assigning Mark to the sixth decade of the first century.

The sixth decade is what we could call the years A.D. 51 to 60, so it’s basically the decade of the fifties.

This is because the first decade starts with A.D. 1, the second decade starts with year 11, the third with year 21, and so on.

The sixth decade thus starts with A.D. 51 and runs through the rest of the A.D. 50s, and von Harnack thinks that the internal evidence in Mark doesn’t in any way stop it from being written in the A.D. 50s at the latest.

But what about the external evidence from tradition?

Von Harnack goes through multiple early Christian sources that mention this subject, and he ends up concluding:

The Date of the Acts and of the Synoptic Gospels

If we compare this conclusion from the evidence of tradition with the date presupposed by the chronology of the Lukan writings, we find that they are not contradictory. Tradition asserts no veto against the hypothesis that St. Luke, when he met St. Mark in the company of St. Paul the prisoner, was permitted by him to peruse a written record of the Gospel history which was essentially identical with the gospel of St. Mark given to the Church at a later time; indeed, the peculiar relation that exists between our second and third gospels [i.e., Mark and Luke] suggests that St. Luke was not yet acquainted with St. Mark’s final revision, which, as we can quite well imagine, St. Mark undertook while in Rome.

Seeing, then, that tradition, though it does not actually support, nevertheless does not contradict the view, gained from our investigation of the Lukan writings, that St. Mark must have written his gospel during the sixth decade of the first century at the latest, this date may be regarded as certain.

Von Harnack thus concludes that—while Luke was at Rome with St. Paul—he read a copy of Mark and took material from it, and I think this is a plausible scenario.

I’m less sure that Luke saw an early version of Mark that is different from the canonical version we have in the Bible today. I’m aware of this being proposed and the arguments used for it, but I’m less certain.

Given how expensive bookmaking was in the ancient world, I’m always hesitant to propose hypothetical editions of books that we don’t have any clear evidence for.

Every lost, hypothetical edition of a book would have cost the equivalent of several thousand dollars to make, so I don’t think we should be proposing that an author like Mark spent thousands of dollars on an extra version of his book that we don’t have—unless we have quite significant evidence.

However, I agree with von Harnack that neither the internal nor the external evidence for Mark points to it being written later than the A.D. 50s.

In fact, that’s when I also place it. I think Mark was written in the 50s, and I estimate that it may have been written in the middle of that decade, or around A.D. 55.

So—in my view—score another for von Harnack.

Von Harnack on Matthew

That leaves us with one more Synoptic Gospel to consider—Matthew—because von Harnack doesn’t consider the Gospel of John in his book.

When it comes to Matthew, he’s less definite about which decade it was written in, and he only treats it briefly.

On the one hand, he writes:

The Date of the Acts and of the Synoptic Gospels

The book must be placed in close proximity with the destruction of Jerusalem. In its present shape, however, it should be assigned to the years immediately succeeding that catastrophe.

So von Harnack thinks that Matthew was written “in close proximity with the destruction of Jerusalem,” which happened in A.D. 70. But close proximity could mean either a little before or a little after that.

Personally, I largely agree with that. I estimate that Matthew was written in the early A.D. 60s—around A.D. 63—though that’s based on the fact that I date Paul’s stay in Rome a couple of years earlier than von Harnack does. If I was using his dates, I might estimate around A.D. 65. In any event, not too far from the destruction of Jerusalem.

Von Harnack says that in its present shape, [Matthew] should be assigned to the years immediately succeeding that catastrophe.

Here he’s referring to the edition of Matthew that we have in our Bibles today, but he think that there were earlier versions of Matthew that were slightly different. Maybe they have an extra verse or two added somewhere.

And this I don’t have a problem with, because verses and even short passages can be added or deleted from a manuscript through the normal scribal process, without proposing that there were multiple, substantially different editions that we don’t have evidence for.

But von Harnack is not convinced that Matthew was written, after 70. He says:

The Date of the Acts and of the Synoptic Gospels

And yet composition before the catastrophe cannot be excluded with absolute certainty.

He then has a footnote where he explains:

The Date of the Acts and of the Synoptic Gospels

In [my Chronology], I have written: “I could sooner convince myself that Matthew was written before the destruction of Jerusalem than believe that one decade elapsed after the catastrophe before the book was written.” Chap. 27:8 and many other passages are rather in favor of composition before the catastrophe.

In other words, if he had to choose between Matthew being written in the 60s or as late as the 80s, he would sooner believe that Matthew was written in the 60s, as I do.

As one piece of evidence for this, he cites Matthew 27:8, which concerns what happened after the temple authorities use the money Judas insisted on returning to buy a potter’s field as a place to bury strangers, and Matthew says:

Matthew 27:8, ESV

Therefore that field has been called the Field of Blood to this day.

Yeah, that does sound like the Field of Blood is still in use as a place to bury strangers when Matthew was writing his Gospel, and that makes it sound like Matthew was written before the destruction of Jerusalem in A.D. 70.

And von Harnack says many other passages are rather in favor of composition before the catastrophe.

So von Harnack doesn’t come down clearly on one side or the other about whether Matthew was written before or after A.D. 70.

He seems to think it was written a little after, but he’s also open to it having been written before.

Conclusions

So where does that leave us with von Harnack and the Synoptic Gospels?

He thinks Matthew was written shortly before or after A.D. 70, and he seems to lean shortly after—so maybe A.D. 72.

He thinks Mark was written in the 50s at the latest, and maybe before that.

He thinks Luke was written before 62.

He doesn’t address John.

And he thinks that Acts was written around 62.

For comparison, I think Matthew was written around 63.

Mark was written around 55.

Luke was written around 59.

John was written around 65.

Acts was written around 60.

And I’ll give you the reasons I support these dates in future episodes.

Von Harnack’s and my views aren’t quite the same, but they are quite similar.

Even though von Harnack was a theological liberal and I’m not.

It just goes to show you what can happen if you set ideology aside and think through the evidence with an open mind.

* * *

If you like this content, you can help me out by liking, commenting, writing a review, sharing the podcast, and subscribing

If you’re watching on YouTube, be sure and hit the bell notification so that you always get notified when I have a new video

And you can also help me keep making this podcast—and you can get early access to new episodes—by going to Patreon.com/JimmyAkinPodcast

Thank you, and I’ll see you next time

God bless you always!

VIDEO SOURCES:

Bart Ehrman video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=768D9sqYdE4